On the Origins of Bitcoin

With the extension of traffic in space and with the expansion over ever longer intervals of time of provision for satisfying material needs, each individual would learn, from his own economic interests, to take good heed that he bartered his less saleable goods for those special commodities which displayed, beside the attraction of being highly saleable in the particular locality, a wide range of saleableness both in time and place.

These wares would be qualified by their costliness, easy transportability, and fitness for preservation…to ensure to the possessor a power, not only “here” and “now” but as nearly as possible unlimited in space and time generally, over all other market goods.

It must be reiterated here that value scales do not exist in a void apart from the concrete choices of action.

Table of Contents

- 1. The battle that never was: The regression theorem versus Bitcoin

- 2. The “money or nothing” fallacy

- 3. Scarcity by the numbers

- 4. On technical concerns and comparative realism

- 5. Show your work: Narrow logical steps

- 6. The presence of pre-existing price constellations

- 7. Taking it back to steak, eggs, and flour

- 8. 120,000 years of “mere” collectibles

- 9. Technical and economic layers always present

- 10. The importance of system and unit perspectives

- 11. A well-documented illustration

- 12. The first emergence of Bitcoin prices for money

- 13. Distinguishing the early value components

- 14. Chalk this one up for the crazy ones too

- Appendix A: Monetary interpretation by year

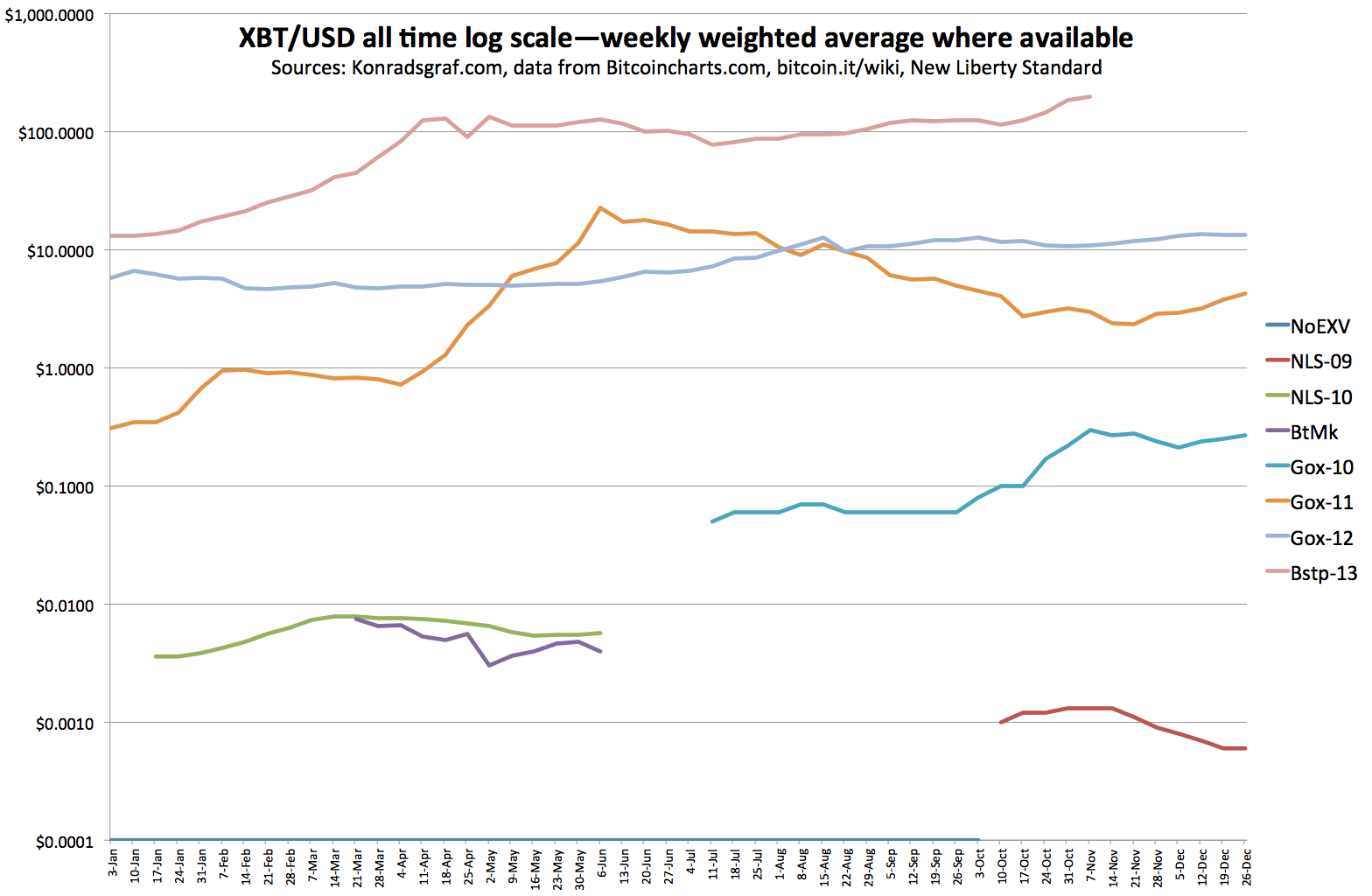

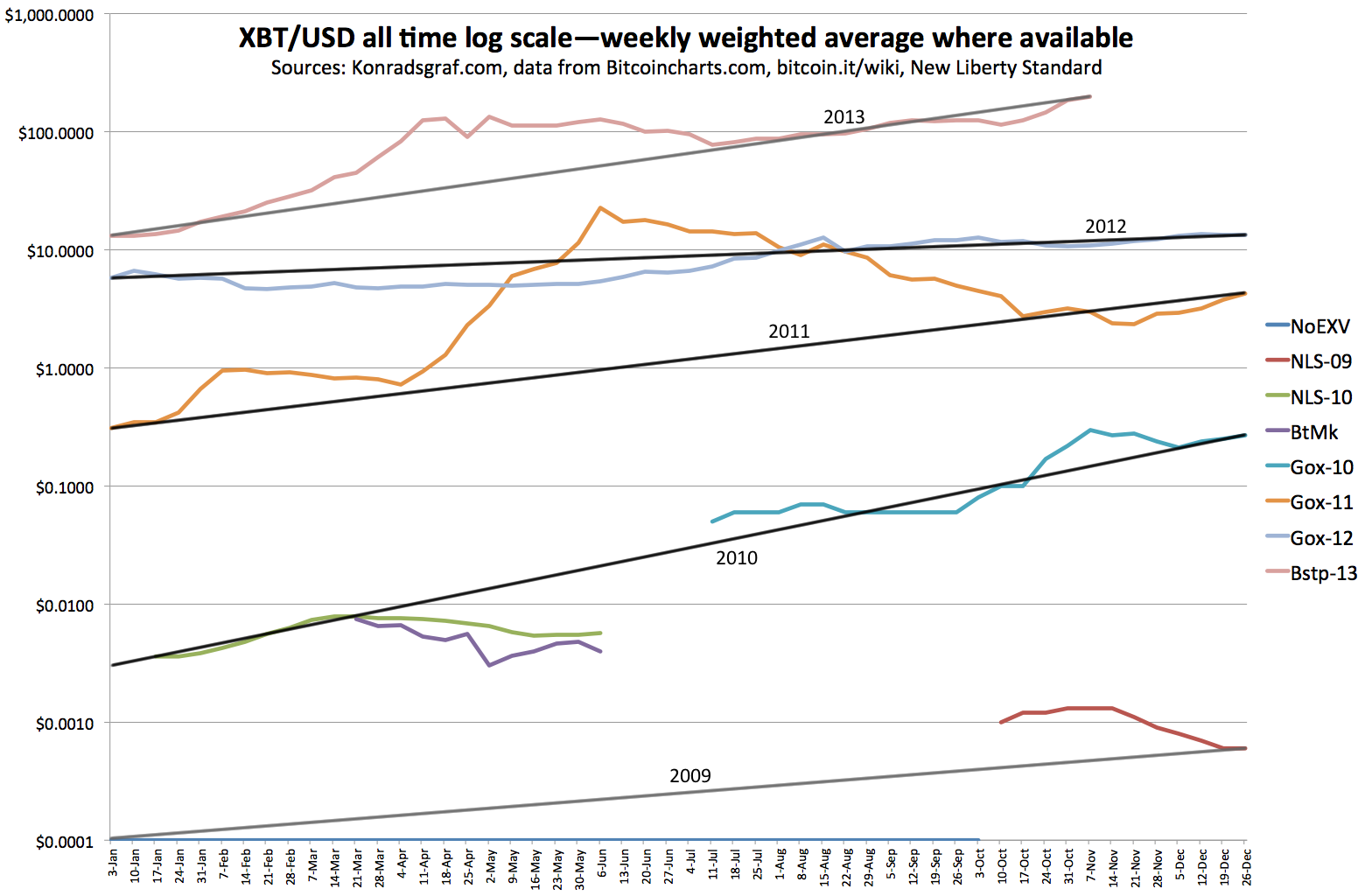

- Appendix B: Five-year price formation chart

- References

- About the Author

- Notes

1. The battle that never was: The regression theorem versus Bitcoin

The regression theorem covers several distinct steps in the theoretical explanation of the market evolution of money.1 It addresses the process by which a medium of exchange emerges out of barter, the process by which a dominant money emerges out of a constellation of competing media of exchange, and the way user perceptions of past prices influence their evaluations of the purchasing power of money looking toward the more or less distant the future. These several distinct issues are not always sufficiently differentiated in discourse.

This developmental-sequence account contrasts with the assignment and state theories of money, which hold that money is an otherwise valueless claim ticket and that it is created and regulated by rulers for use among their subject populations. This latter view might be somewhat ungenerously dubbed the ruler’s hand-wave or monetary-creationism theory of money. Another view has it that money is a mysterious “social illusion” agreed only by arbitrary convention, regardless of whether state actors have played an integral or an incidental role in the illusion building. However, such accounts seem to offer little explanation as to how and why one such illusion ends up beating out all other candidate illusions in specific times and places.

It is in contrast to such unsatisfactory accounts that the action-based and evolutionary “Austrian school” explanations have long stood. These hold that 1) money is also an economic good in itself, not merely a substitute claim ticket on the social stock of actual goods, and that 2) money’s development can be traced to specific, step-by-step economic processes. Each of these steps, according to the Austrians, and Ludwig von Mises in particular, can be clearly explained in terms of human choices and actions in universal-theoretical terms, and then also illustrated with empirical-historical examples.2

The regression theorem explains a set of logical implications derived from core economic-theory concepts such as “good” and “medium of exchange.” However, the step-by-step market-evolution account associated with the regression theorem has usually been learned and understood by students of economics in the context of historical examples, all of which were tangible goods.

The initial valuations of less tangible paper, and entirely intangible digital, fiat money units are also traceable to more tangible goods in their long historical pedigrees. Combinations of redemption defaults (legalized “suspensions of payments”), gradual public acquiescence for lack of better alternatives, and legally forced fixed-rate transitions enabled increasingly abstract units to take over the social functions of their more tangible commodity ancestors. Political actors could then much more freely manipulate the quantity of money, particularly after the last vestige of a physically-linked barrier to fiat inflation fell in 1971.3

It is important to distinguish a free-floating, organic price development such as Bitcoin’s from legally forced fixed-rate conversions from one retiring official money to its new official replacement.4 A recent example of this was the legally orchestrated replacement of several national European political currencies with the euro. The euro (both paper slips and computer digits) inherited its initial valuation as money from the monetary valuations of its predecessor currencies through forced fixed-rate conversion. These predecessor monies had, in turn, likewise taken up their initial values from legally fixed exchange rates against precious metal bullion and precious metal coin monies, exchange rates which were progressively degraded and eventually swept away entirely.

Such legally forced value conversions from one money to an official successor contrast sharply with original monetary evolutions on the market. Discussions of the latter have typically used the word “commodity” to neatly categorize all of the available historical examples. This word seems to specify some tangible, divisible material.

When Carl Menger set out the problems he was to address in “On the origins of money” in 1892,5 he both framed the origins issue in terms of two competing explanatory paradigms and used this “commodity” terminology throughout.

Is money an organic member in the world of commodities, or is it an economic anomaly? Are we to refer its commercial currency and its value in trade to the same causes conditioning those of other goods, or are they the distinct product of convention and authority? (13)

One reason for using the word commodity was that goods literally traded on commodities markets, such as corn and cotton, were referenced in discussions of pricing, liquidity, and distinctions between the respective positions of buyers and sellers. The use of more liquid market-traded commodity examples were contrasted with unique or special-use items such as paintings or technical instruments, for which it is much easier and quicker for a buyer to locate a ready seller than it is for a seller to locate a ready buyer.

Nevertheless, for modern readers in the information age, with its abundance of incorporeal “digital goods,” the word “good” should serve in place of commodity with less materialistic distraction. Several of the great Austrian writers, foremost Mises, repeatedly insisted that we should not be misled by the exterior appearances of things. Nevertheless, materialistic connotations seem to have conspired to lead observers into confusion when it comes to interpreting the Bitcoin digital currency and payment system.

This is understandable in view of the intangible and technically elusive nature of the units traded within the network—the likes of cryptographically “signed inputs” and “unspent outputs.” From a technical point of view, as opposed to a user point of view, a specific item that can be pinned down as “a bitcoin” does not even exist. Nevertheless, it is sufficient from an end-user point of view to use the metaphor of the putative existence of such an item to understand how to make advantageous use of the actual Bitcoin network.

Bitcoin’s many arcane technical elements cross the domains of several highly specialized fields of study. While important on their own terms, such details can be a distraction to the specifically economic side of the analysis, which is concerned with the actual structure of end-user actions. Much as the use of silver coins in trade was not seriously challenged based on the fact that silver is “really” just a peculiar configuration of subatomic particles among many other possible configurations, so one should not be distracted by the fact that Bitcoin is “really” just a peculiar arrangement of specified cryptographic relationships maintained and verified within a global, peer-to-peer, open-source computing network. Chemists and metallurgists are in the businesses of understanding the details of the one; cryptographers, computer scientists, and programmers are in the businesses of understanding the intricacies of the other.

However Bitcoin actually works “under the hood,” and regardless of speculations and opinions on its long-term prospects, it is now already being traded year after year as a good and it is now being used as an increasingly widely accepted medium of exchange on a global scale. It thus now does fall under the relevant action-based economic-theory categories and each of their logical implications. No contradiction between Bitcoin and the economic-theory insights associated with the regression theorem is possible. Nevertheless, understanding how it is that no such contradictions exist seems to have proven a challenge.

I have written and spoken on Bitcoin and the origin of money several times, as have Peter Šurda and Daniel Krawisz.6 As fairly fundamental confusions seem to nevertheless persist, I offer a number of additional approaches to, and perspectives on, this topic below. Not only must Bitcoin be more carefully understood, but also the regression theorem itself, including its abstract and action-based formulation and its several distinct components. Moreover, adding some additional ways of looking at the nature of money further clarifies the issues.

2. The “money or nothing” fallacy

An informal survey of some economists’ opinions on whether Bitcoin is “money” or not recently appeared on the Economic Policy Journal website.7 The fairly reasonable consensus was that Bitcoin is functioning as a medium of exchange now and could someday become counted as “money” if and when it is much more widely accepted and becomes the “commonly used” or “most commonly used” medium of exchange.

Opinions on the application of words such as money are much less important than understanding what is happening in the real world. In an astute comment under the above report, Peter Šurda, a Bitcoin researcher informed in Austrian school approaches, labeled an ongoing obsession with judging Bitcoin based on the money question as the “money or nothing fallacy (if Bitcoin is not money, it’s nothing).”

Moreover, I recently argued that rather than the vague “commonly used,” a more precise criterion for qualification as “money” would be which unit most people in a community are using for pricing and accounting (economic calculation). That said, the identification of one item as money by no means eliminates the possibility of actually paying designated prices with whatever other media a seller is willing to accept at an agreed exchange rate for the asked price expressed in the local common unit of pricing.8 For those who wish it, for example, there are already payment services that enable the instant conversion of received Bitcoin payments into fiat money. Developers are also working to enable similar services for buyers. This would give the option for some users hesitant in the face of Bitcoin’s current early-stage price volatility to only hold Bitcoin for fractions of a second. Such services enable anyone to take advantage of the payment-system aspects of the network while avoiding volatility risk if they wish to.

Yet the view that there is an alleged opposition between the reality of Bitcoin and the supposed implications of the regression theorem is nothing if not persistent. Another commenter on the EPJ survey wondered whether, with the ongoing successes of Bitcoin becoming increasingly difficult to deny, the regression theorem might not have to be revised out of Austrian economics. This sentiment, which reappears in online discussion threads from time to time, might seem reasonable at first, but only when based on the widespread misconception that the theorem actually does require that any (sound) money be material or tangible, at least in its origin or “backing.”

I have previously argued why there is no theoretical reason that a medium of exchange has to start out being material.9 It only has to be a scarce good. The digital age, and Bitcoin itself, have made it clear that goods do not have to be tangible. Despite word choices such as commodity in classic writings on this subject, there is no fundamental economic reason that a physical material has to be what secures the essential monetary characteristics—foremost scarcity. The supposed need for tangibility is an association leftover from the range of examples that was available prior to the internet age.

3. Scarcity by the numbers

In our day, we are quite familiar with digital goods. Part of the seeming magic of Bitcoin is that it is one of the first digital goods that is also scarce and rivalrous in its nature. This contrasts with almost all other digital goods, which are fundamentally copiable and non-rivalrous.10 This means that they can be copied with no effect on the “originals” that the copies are made from and the resulting multiple copies can all be used simultaneously without direct mutual interference among users.11

The prototypical non-rivalrous (non-scarce in the property-theory sense) digital good is a digital file. Some have tried to render digital files scarce by appending legal or technical restrictions (copyright and DRM) on top of their basic underlying nature of copiability. Such attempts to create scarcity after the fact are meaningfully distinct from a scarcity that is built in as an inseparable characteristic of the nature of the good itself. Bitcoin’s scarcity is a component of what it means for it to be Bitcoin as opposed to something that is not Bitcoin.

Even most other types of digital currencies prior to Bitcoin were capable of being copied (increased in quantity) on the decisions or policies of a central issuer. Examples of existing centrally managed digital currencies include World of Warcraft gold and fiat-currency-denominated central bank accounting entries. WoW inflations can occur based on various changes in the balance of game parameters. As for central bank units, the supply of both notes and the now-dominant arbitrary digital account entries is at the ever-shifting discretion of committees of carefully screened political appointees. Such shaky foundations are obviously incapable of supporting a reliable digital money for wider applications in society.

Bitcoin has overcome in a completely new way the eternal threat that a central issuing authority will arbitrarily dilute the value of a digital unit. It is not within the scope of the current study to describe the many interlocking technical details, nuances, and differentiations by which this has been accomplished. The key point here is that Bitcoin sets its quantity growth trajectory within the definition of what the unit is and how it is created. A digital currency with more than a theoretical potential of 21 million bitcoin units (2.1 quadrillion Satoshis) would not be Bitcoin, by protocol definition. Anyone is free to make up some other Bitcoin-like digital currency, and many have done so. None of those other units are in any sense bitcoins. They are litecoins and freicoins and so forth.

4. On technical concerns and comparative realism

Still, some are naturally concerned that a total network failure could leave Bitcoin suddenly valueless. It is important at the outset to identify this as a claim that must be considered on a largely technical, rather than economic, basis. It is best addressed through reference to knowledge and debate within the most relevant fields. Among these fields is cryptography, especially hashing algorithms and the use and verification of cryptographic signatures; peer-to-peer network design and security, the principles of constructing unforgeable decentralized cryptographic ledgers, and the intricacies of overcoming the distributed consensus, or Byzantine Generals’ problem (having Byzantine fault tolerance), with some help from the concept of a distributed timestamp server.

In considering imagined scenarios of catastrophic system failures or even more modest technical difficulties, relevant knowledge of such fields can also be usefully supplemented in places with specifically economic methods, such as for economic analysis of mining profitability and miner incentives. It should not be necessary to become an expert on the inner technical details of each field to make useful reference to them. It should be sufficient to understand the relevance of those fields well enough to comprehend how the various technical details play into the functioning of the system and the development of informed assessments of its reliability.

For the economist looking at the economic use of Bitcoin, it should even be a sufficient starting place to observe that all those persons actually using Bitcoin do in fact judge it, however rationally or otherwise, to be sufficient to serve the purposes to which they are putting it. This includes the various time scales that they have in mind for those purposes, each according to his own discrete series of judgments at the margin.

Just as we do not expect everyone to become an aeronautical engineer before buying a plane ticket, it is not necessary to obtain any crypto-wizard math status to use or even productively analyze Bitcoin. It is only necessary, each by his own standards, to decide that the system is good enough for his own particular set of envisioned uses.

Without delving into any such highly technical content,12 several general considerations may help put such system-catastrophe concerns into better perspective. At the absolute worst case, even if Bitcoin were to fail due to some unanticipated weakness, the concept and usefulness of cryptocurrency in general has already been proven in practice. A Bitcoin upgrade or even replacement several times more secure could be rolled out, developers having already learned well from whatever currently unimagined errors might have improbably led to a large, unanticipated technical fault.

In the much more likely case, though, it is necessary to recognize that, as a decentralized, all-voluntary, open-source protocol, Bitcoin is distinctly capable of being adapted and updated on an ongoing basis. Its programming contributors, users, and even top critics all work relentlessly (at high levels of relevant technical sophistication) to imagine, discuss, weigh, anticipate, and address constellations of system threats, major and minor, real and theorized.

Part of open-source security culture that those outside it seldom appreciate is that highly skilled programmers, whether white-hat or black, make it their personal missions to try to break “secure” systems. From the ultimate point of view of the actual strength of functional network and data security, this steady threat and testing interplay is considered an essential feature rather than a bug in security development. The very fact that a secure system—particularly one such as Bitcoin with a direct monetary reward in the form of extracted coins—actually does remain secure over time, year after year, already suggests, at minimum circumstantially, that it is continuously passing a battery of ongoing security tests conducted by motivated and skilled adversaries and motivated and skilled supporters alike.

Moreover, following even a highly hypothetical catastrophic breakdown, a revised Bitcoin network could potentially be relaunched from the existing block chain, starting from the last-verified constellation of ownership. As Jay Schmidt often argues, the real heart of Bitcoin is the block chain record of current ownership status itself. The block chain serves as something like a massive global title registry. Michael Goldstein has movingly put the easy-to-underestimate social importance of such ownership records in a larger context by quoting from Milan Kundera’s novel, The Book of Laughter and Forgetting (1978): “The struggle of man against power is the struggle of memory against forgetting.”

The technical mechanisms and network operations that surround the block chain are each specific and upgradeable technologies or methods for changing the records in an acceptable and verified way. Each of these surrounding elements can be modified, improved, or replaced indefinitely into the future (naturally some elements are easier to alter; other, more central ones more challenging). Bitcoin is in this sense not so much a fixed target, but a highly adaptive moving one.

It must also be recalled that there is no perfection in this real world. There exist only relatively better and worse actual options. For example, political monies, far from being merely hypothetically insecure, actually do steadily and precipitously decline in end-user purchasing power. They do so now and have done so in every known case throughout history.13 Gold and silver, for their parts, have also ended up failing as monetary systems in practice. Some configuration of the ancient and enduring state-bank inflation and debt alliance has always eventually resorted to confiscating such valuable substances from any significant storage vaults and from the public generally, in part or in whole, finally resorting to replacing precious metals in monetary circulation entirely with freely multipliable fiat papers and account entries.

Precious metals themselves, while they have certain relative superiorities to political monies (and other relative weaknesses), are in principle still more susceptible to the weakness of aggregate supply variation than Bitcoin, especially in the long term. In the extreme, for example, they would be susceptible to the mining of mineral-rich asteroids and the return of extracted and refined metals.14 In contrast, since Bitcoin’s supply trajectory is pre-determined as part of the definition of what it is, it is impervious to such physical changes in the constellation of available mineral resources and processing technologies.

A mixture of real-world pros and cons must be considered in comparing long-term prospects for the use and stability of various options. Real persons facing marginal decisions ought to ideally balance both the pros and cons of their actually available options, as opposed to assuming an imaginary or eternal perfection for some of them.

For hard-money enthusiasts in particular, the traditional story of the once and future superiority of precious-metal backed monies over fiat monies must be revisited in light of the fresh emergence of entirely new monetary forms that were never before anticipated in the old binary vision. The past must be learned from. Yet it has also been wisely observed that, “there is no future in the past.”

5. Show your work: Narrow logical steps

One element of ongoing confusion behind the “Bitcoin versus regression theorem” dialectic is that the latter covers not one, but at least several distinct theoretical issues, each of which is rather specific.

One of these is to explain the purchasing power of money in terms of the level of prices without resorting to a circular argument in which prices today explain purchasing power today and vice versa. The solution to this was to introduce a time element. The purchasing power of money “today” (going into the future) is based in part on user assessments of its purchasing power from “yesterday” (user perceptions of the most recent past constellation of prices).

Yet this answer already raises the next issue: What happens when the “regressing” takes us all the way back to a time before what was to become a medium of exchange had gained any medium-of-exchange value component? This is the aspect that relates most directly to the theoretical confusion over Bitcoin. It explains the first emergence of any kind of medium of exchange out of a previous state in which it was not one yet.

Mises emphasized in Human Action15 that the regression theorem is not a generalization from historical cases, but the identification of a universal theoretical necessity:

It does not say: This happened at that time and at that place. It says: This always happens when the conditions appear…no good can be employed for the function of a medium of exchange which at the very beginning of its use for this purpose did not have exchange value on account of other employments…It must happen this way. Nobody can ever succeed in constructing a hypothetical case in which things were to occur in a different way. (407; bold emphasis mine)

Mised did not say “should be” or “has been”; he said, “no good can be employed,” a claim of logical impossibility. This “origins” aspect of the regression theorem (as opposed to the purchasing power and dominant-money aspects) states that no good can be valued for use as a medium of exchange prior to taking on such a use for the first time. This is a statement of necessity, of definition.

Moreover, to take on a value component as a medium of exchange, a good must first be valued based on some other value component in the eyes of some of the relevant actors. This other value component must obviously have been distinguishable from any subsequent medium-of-exchange value. This is because such subsequent components cannot already exist prior to their first emergence. Again, this follows by definition of the challenge of avoiding logical circularity.16

When young people take a math class, the teacher requires that the students “show their work,” demonstrate each of the stages in the process of arriving at a conclusion. This can be tedious and requires many small steps. The regression theorem in its context provided a couple of these “show your work” logical steps.

Recall that elements of the regression theorem were honed in the context of debates between competing accounts of the origins of money. One side claimed that money was an invention of the state and had been decreed by rulers for the benefit of society. Its value was determined and regulated by various state actions. Another side claimed that money functioned as a good in itself, emerged out of market processes, and was only then taken up and manipulated in various ways by rulers over time.

The mostly German state theory of money side17 found some technical holes in the arguments of the market evolution side, who being associated with the University of Vienna down south, were labeled as (those country-bumpkin) “Austrians.” The critics had essentially demanded that the market-evolution side “show their work” when it came to each step of their theory of the market emergence of money (while assuming that they would not actually succeed in doing it).

The origins aspect of the regression theorem covers a narrow period of transition from when a good that was not used as a medium of exchange comes to be used as one for the first time and then gradually gains social traction in this role. This origins aspect is only required to explain the first emergence of a medium of exchange (a means of payment). It is not also required to explain the next phase of emergence of a money (a dominant unit of pricing and accounting) from a field of competing media of exchange.

The latter is a competitive and network-effect driven process in which one of the options on the market rises toward the top in a given context. One of the key characteristics of such goods is what Menger called the degree of saleability, one indicator of which is the narrowness of the gap between the price at which one can immediately buy it and the price at which one can immediately sell it (Menger 2009, 24–25, fn 2).

In explaining the emergence of money from a field of competing media of exchange, the sequence goes forward in time, the opposite of “regressing” backward. Analytically regressing backward, as an evolutionary metaphor illustrates, will tend to miss all other branchings on the tree. It will only find one direct chain of ancestors tracing back from the starting point of the regression. Going forward in time, however, can reveal other branchings (all competing media of exchange), including both dead ends and new beginnings. A repeating pattern in the long-term evolution of life is the dying out of old species that were once dominant and the emergence of novel dominant species, often with radically different sizes, speeds, habitats, and strategies compared with the predecessor kings of the jungle.

This is why running regression logic only backward in time and not running it forward in addition, could lead to oversimplifications. The only options seen by going backwards from the current money will logically be the direct ancestors of whatever has ended up becoming the current money to that point in time. It will miss anything not in that particular lineage. Running the process forward again from each start-up medium of exchange may reveal competitors in different lines, many of which may have been tried, some of which succeeded to some degree, some of which may be gaining ground, and only one of which is the dominant unit of pricing and accounting in a relevant market area—up to the present time.

6. The presence of pre-existing price constellations

It is a simple matter today for people to value the relative purchasing power of Bitcoin by referencing its exchange value against local money using a public real-time market exchange rate available on any internet-connected device. Bitcoin functions now as a medium of exchange. I have defined this as something that can be tendered to pay prices. Prices are denominated in “money,” which I have defined as the dominant unit of pricing, accounting, and economic calculation in a given context. There is no fundamental reason why Bitcoin could not also some day take over such wider roles if it becomes relatively more stable, more global, or otherwise more suitable for this than its nearest active competitor. It already fills the function of price-denomination within certain narrow contexts inside the Bitcoin economy.

In contrast to this situation, some presentations of the regression theorem have treated the evolution of a medium of exchange in a context in which no previous unit of pricing exists. This means that no constellation of relative prices was in use in society at the outset.18 The case of the original evolution of Bitcoin introduces the need for some qualifications relative to such accounts in that it emerged as a new medium of exchange in a context in which an advanced array of relative money prices for goods and services already existed.

Bitcoin’s evolutionary challenges were therefore eased considerably relative to a situation in which no knowledge of relative prices on the market existed. In this counterfactual case, an entirely new array of market prices directly relative to Bitcoin would have had to develop through trial and error processes of direct trades of Bitcoin for bacon, Bitcoin for eggs, and Bitcoin for horses, while also trying to reference unmediated rates of exchange between eggs and bacon, between bacon and horses, and so on—all until a reasonable constellation of relative market prices began to take shape again denominated in the new unit.

In the factual case, however, Bitcoin only had to jump a much simpler hurdle (though still quite challenging in its own way). It only had to develop a market exchange value against the existing money in each location of trade. It could then “bootstrap” its relative medium-of-exchange value onto the existing full constellation of market prices, as these were already expressed in monies in each geographic region.19

To this day, most things bought and sold with Bitcoin are priced in local monies. A current exchange-rate-based equivalent sum of Bitcoin is then used to actually pay those prices.20 Insisting on an independent evolution of a new constellation of relative prices directly in terms of Bitcoin, however, would have been absurd and unnecessary. There was no practical need to reinvent that particular set of wheels in the relevant places and in the timeframe 2009–2010.

Whether something like Bitcoin could possibly emerge directly out of a state of pure barter is so hypothetical as to reach into the realm of not even science fiction, but fantasy. This is because a state of pure barter could only support an economy so primitive and close to direct production through hunting, gathering, and maybe some limited farming, that the requisite electrical output, internet infrastructure, computer chip development technologies, screens, and so forth could not also exist or persist in the posited context, making the hypothetical moot.

While the principles of the regression theorem are applicable to any instances of the universal, the requisite technical context here also includes a stage of complex social and technical evolution built on a wide-ranging division of labor and on other previous stages. Such high technologies could obviously not continue to exist if their foundations were lost.21 A pure state of barter could only support perhaps a few percentage points of the current human population at best. This means that the loss of the convenience of an internet money would be among the least of the difficulties to be encountered in such a scenario.

7. Taking it back to steak, eggs, and flour

A fairly primitive hypothetical can nevertheless help bring the “origins” component of the regression theorem down from the abstractosphere, where confusions can more easily persist, into a realm much closer to concrete experience. It is not enough to merely show that Bitcoin is explainable in terms of economic theory. It should also be made clear that the regression theorem is not threatened by this empirical development.

Starting out in a hypothetical pure barter scenario, I want to trade steak for some flour. However, the miller is an ovo-vegetarian. The double coincidence of wants needed for a trade to take place is absent.

I need to find something else to trade with the miller if I am to buy flour from him. Whatever I obtain to facilitate this trade will already technically function as a “medium of exchange” within the narrow context of my desired transaction, regardless of what anybody else is doing in my hypothetical community. A medium of exchange, in this most bare-bones sense, is a good that facilitates an exchange that is not happening directly between two parties because of the absence of a matching mutual coincidence of wants.

Uptake of a medium of exchange from zero starts with a single creative act of two-step trade among three parties. Only once it has begun to be put into practice can it possibly begin to be copied and spread. The practice of indirect exchange itself is an invention and a discovery. Subsequent processes can sort out which kinds of goods will tend to be more or less useful in this social function in a given context. Finding out how to pull off indirect exchanges more frequently and effectively, and with what, is a layer of experimentation distinguishable from the general idea of engaging in indirect exchange.22

In this case, I realize that as an ovo-vegetarian, the miller eats eggs. I walk over to Friedrich the chicken farmer and trade a steak for some eggs. Then, I walk back to the miller and trade eggs for flour. The requirement here is that the miller will accept eggs. If he does not, my indirect exchange attempt fails. If it succeeds, the eggs have already functioned as a medium of exchange within that transaction.

The miller has to value the eggs as eggs for this to count as a first emergence of indirect exchange value for eggs. I obtain eggs for their use as a medium of exchange for my transaction. In doing so, I value them for this purpose. If the miller does not accept eggs, however, my valuation of the eggs as a medium of exchange is a failed one, an entrepreneurial loss on my part. I am just stuck with some extra eggs. This endeavor depends on my practical success in understanding what my prospective trading partners will or will not accept in trade.

The only way this value component of eggs as a medium of exchange can possibly come into being at first is if someone else will accept them as eggs because they want eggs, not because they already want to trade the eggs again with someone else. A circular process of self-reinforcing social demand can only come to function after the practice of indirect exchange using eggs has begun to get moving in a given social context. Only then can expectations of this added component of widening saleability begin to build among the relevant actors. After the new medium-of-exchange value component does emerge and persists in a given context, the non-medium-of-exchange value components could theoretically then fade away entirely.23

However, eggs in particular will not tend to get very far in this role. They spoil after awhile. We could use some expiration dates, but this creates a fatal heterogeneity among the units due to age discounting. And eggs are fairly heavy and hard to transport far without breaking. Much more durable items have repeatedly become more successful in this role.

8. 120,000 years of “mere” collectibles

The first likely historical media of exchange that show up over and over again in the archaeological record in many different geographic areas are strings of beads carved from various seashells. The earliest known find of such beads far from the ocean is in modern Algeria and dates from about 120,000 years ago. When items are found this far from source, it is considered a good sign that they had probably been obtained in trade.24

Nick Szabo in his discussions of the origins of money called these kinds of proto-monies “collectibles.”25 They are not useful in what could be considered any practical sense. They are things a lot of people like to have because they like to collect them and wear them. They are distinctive, rare and hard to come by, last a very long time, and are highly portable. Szabo also pointed out the security characteristics of such items. Since they can be worn, a thief is reduced to grabbing them directly off a person rather than just picking them up quietly unseen. Such small collectibles can also be easily buried or otherwise hidden during times of trouble and recovered at some indefinite later time.

They were not quite monies in a modern sense, but were used to perform some of the same functions: storing value over long periods, transferring it among generations such as on the occasion of weddings, using it in larger trades or to help seal pacts, and as a fallback, enabling buying from neighboring groups in the face of a local dip in food availability. Yet all such uses would have to have been discovered gradually after the beads had already come into existence as ornaments. They had to have some non-trading value before they could begin to be traded.

It so happens that such strings of shell beads have characteristics that we now understand in retrospect to be essential characteristics of media of exchange and value storage. They are durable, divisible, portable, and to some degree interchangeable (though different colors and types could naturally be valued differently). Beads can be unstrung, counted, and restrung in different numerical configurations.

And so, it is easy to imagine how indirect exchange using them could begin to gradually develop and spread. Archaeological evidence highly suggestive of long-distance trade using strings of beads goes back many tens of thousands of years and is found in many different areas.

Later on, we find that people also like to collect bits of shiny metals that were not really good for much that was “practical” either. People fashion them into wearable decorations and eventually some other items such as fancy vessels. Viewed on a long time scale, the use of precious metals in coinage is a rather recent historical development. Lydian coinage around 700 B.C. is typically cited as a first precious metal coinage. It was made from electrum, a natural gold/silver alloy (with naturally varying percentages of each). This was prior to the development of effective refining methods. The sometimes-touted industrial and electronic uses of gold and silver are all quite modern and therefore entirely irrelevant to the first emergence of these metals in a monetary trading role in various places many centuries earlier.

Bitcoin, during at least its first year or two, likewise could easily have been described as a strange and useless curiosity with no practical value. Only a few programmers and cryptographers had any belief that Bitcoin might end up becoming useful for anything other than playing on computers. Bitcoin was an idea and then a computer science and cryptography experiment. It was not clear in advance or even after it started if it would work technically or take off economically. It arrived after a long trail of failed experiments. Why should it not become just another such failed experiment?

Only later, did a wider population begin to hear about the possibilities of using bitcoins, those otherwise pointless scarce digital objects to trade for “real” goods and services.

But of course, we have seen versions of all this before. We have seen it with shell beads tens of thousands of years ago, and we have seen it with people collecting and toying with soft shiny metals several thousands of years ago. Now, we see it with digital ledger entries forming digital objects that do not actually exist at all in certain senses.26

In framing the fundamental question of the origins of money in 1892, Carl Menger observed that:

What is the nature of those little disks or documents, which in themselves seem to serve no useful purpose, and which nevertheless, in contradiction to the rest of experience, pass from one hand to another in exchange for the most useful commodities, nay, for which every one is so eagerly bent on surrendering his wares? (2009, 12–13)

One way for moderns to approach the challenge of understanding how digital ledger entries that they do not even comprehend could possibly be “really” valuable is to reflect on how odd previous new kinds of media of exchange must have seemed to people in the distant past from their perspectives. Strings of beads are above all impractical and optional objects. Compared to meat, tubers, and berries; compared to spears, clothing, and tools; strings of beads and “real” value must have seemed distant. And yet, with time, quite a few people seemed to enjoy making and collecting them if they could. They were decorative. They were rare and hard to come by. It took a long time to carve them. They lasted a long time (as in, we can still dig them up 120,000 years later). They socially demonstrated a certain power of excess capability precisely because of their impracticality.

Likewise, shiny pieces of silver, gold, or electrum in most places several thousand years ago were not the epitome of usefulness. Wool was warm, meat could feed, a plow could improve the harvest. Weapons could come in handy. What was it with these shiny substances that can be shaped into trinkets and worn?

Imagine how outlandish this may well have seemed to people for whom it was entirely new. Upon hearing that some people at the annual trade meet-up might accept these metals (not even jewelry, just rough hunks of metal), what was a herder to think?

“I will have to see this for myself! You are telling me that people are fool enough to accept little shiny bits of metal for real goods?”

Of course, in retrospect, it is easy for us to understand where this can go. Such metals are strong on a number of monetary characteristics that economists now understand conceptually can help facilitate trade. And, like beads, wearability and hideability of jewelry can confer a certain security and savings advantage. Many Indian women to this day tend to wear their long-term family savings.

But for those lacking such knowledge, what a strange new world this must have been, learning to trade useful things for useless trinkets, time after time, generation after generation, until the practice took hold more widely, until people “bought in” to the bizarre idea that these materials could themselves also be “useful” and valuable not only as wearable pretty objects, but also as units within a social system that facilitates trade.

Indeed, owing to the sorry state of economic education, most people to this day still do not conceptually understand the magnitude of mutual gains that come from wider possibilities for trading, facilitated by money. They do not understand that without these distinctly human practices of trading good for good and using money, only the tiniest fraction of the current population could long survive.

9. Technical and economic layers always present

The case of Bitcoin also shows how the line between invention and discovery is much more tenuous than is usually imagined. In each case of initial monetary evolution, there is both a technical and an economic aspect. Before something can begin functioning in trade, it must first exist in some minimally tradable form. Beads must be carved, pieces of rare metals dug up and cleaned and later shaped or even refined.

It is no different with Bitcoin. Well before the units could begin to function in exchange, they had to be brought into existence in a way that human actors could possibly recognize them, begin to toy with them, and eventually start taking the leap of dealing in them against “real” goods and services. The network first had to be both envisioned and launched. It had to be tested and refined, challenged and proven over time.

In each case of a new monetary evolution, there is a phase during which some usable form of the units that will eventually be traded first come into existence. This is in the technical layer. Only then can a monetary layer possibly emerge with trading of these technically developed units. Both technical and economic layers subsequently continue to evolve and interact, taking forms such as better bead-carving tools, metal refining techniques, or the next Bitcoin software release. Yet it is still important to understand how both technical and economic layers are always present, and not just with Bitcoin.

The technical layers involved in the production and exchange of physical commodity units are obviously quite different from the corresponding technical layers for decentralized cryptographic currency units. Likewise, the technical layers involved in smoke-signaling are quite different from the technical layers involved in internet chat interfaces. Nevertheless, both types of technological methods have managed to fulfill, to varying degrees, the human purposes of channeling messages over distance (the “economic” layer).

What may have taken tens of thousands of years, place by place, for beads, and centuries for precious metals, may now be taking a couple of years and months for Bitcoin. In past cases, the practice of using particular items in trade developed on separate timelines in each geographic context. Today, however, the contexts of trade, imitation, and discovery are defined on a global scale by user demographics and choices on the internet, rather than local geography or the particulars of land and sea trading routes. Instantaneous global communication and news flow, social media, advertising, and modern people’s thorough familiarity with the general concept of large-scale indirect exchange are all now catalysts.

10. The importance of system and unit perspectives

Any monetary system is not only a collection of out-of-context units, but a system. This includes a network of people with a similar social understanding about the trading uses of the relevant units. Isolated objects do not constitute a system of trade.27

With Bitcoin, the “system” aspect is much more prominent than the “unit” aspect when compared with previous market evolutions of tangible media of exchange. The system aspect is now literally a massive computing network—already the most powerful on the planet in raw processing power by a very large margin—an all-voluntary software development network, and untold distributed copies of the block chain unforgeable decentralized transfer record.

Bitcoin units can exist only on the block chain and can only be transferred from address(es) to address(es) within the context of the live Bitcoin network.28 Owning a bitcoin at a given time can also thus be viewed as analogous to owning membership shares in the block-chain-based trading club. All current controllers of bitcoin units are able to use both the trading system and its units for their own purposes according to their degree of self-selected “buy-in” to the system.

Yet buying into a medium of exchange by beginning to use it as one has always implied something more than just buying some out-of-context objects. It means, at least implicitly if not explicitly, demonstrating a small margin of support for the idea that this kind of unit is something that can function as a medium of exchange in society. It is due to the process of more and more people, one by one, making this wider “system” statement by actually accepting, saving, and spending a unit, that it begins to develop beyond a mere collectible item. It is only within the context of an active trading system that this additional valuation cycle can build. This is true for all possible media of exchange as they grow into this role, regardless of incidental technical characteristics such as tangibility versus intangibility.

In previous historical cases, the unit aspect was more obvious and the system buy-in aspect perceivable only more abstractly and indirectly. With Bitcoin, however, the system buy-in aspect is more obvious and explicit, whereas the unit aspect is only perceivable more abstractly and indirectly. It is literally no longer possible to miss the system aspect because Bitcoin units are comprehensible only within the context of the decentralized ledger system that enables reliable first appropriation (mining), storage, and transfer. The underlying reality underpinning its unit aspect is technical and difficult to grasp.

In contrast, precious metal coins, though also fully embedded in a social trading system, stood out from that system by their concreteness and tangibility. With a metal coin, one could still naively imagine that it somehow held value all by itself. However, this was never true. Exchange value is ever dependent on the willingness of a buyer to buy. A medium of exchange value component is likewise always dependent on the implicit expectation of future acceptance by at least one other party. A trading unit can only work within a social trading system.

We saw above that an attempt at indirect exchange of steak for flour would fail if the intended party to the second trade (the miller) does not accept the intended intermediating good (eggs). The medium-of-exchange value component of a good that becomes more generally used in this role can multiply in that others begin more and more to accept it in trade because they also expect that still others will accept it in subsequent trades. This value-building cycle can be circular and self-reinforcing. However, no cycle can begin itself in circular causation. It is the regression theorem that explains in abstract terms what must be present to initiate any such self-reinforcing network-good cycle—some other valuation prior to the beginning of this use.

11. A well-documented illustration

Bitcoin units had no recognized exchange value whatsoever for nearly a year after the Bitcoin network began functioning in January 2009. They also specifically did not yet have any medium-of-exchange uses. They did not facilitate any trades. Instead, programmers and cryptography enthusiasts were running the software, connecting to the fledgling network, trying out the code and working to improve it, mining bitcoins, and sending bitcoins back and forth to each other for fun and experiment.

Peter Šurda has been assembling some first-hand report evidence on this early period. In a recent post,29 he quoted early participant and developer Mike Hearn speaking from his perspective as a new participant in the early days:

I found [Bitcoin] very early on, when no one was using it, so no one, no exchanges, had no exchange rate at all, so they were just completely floating in an abstract space. You know, what was one coin? Well, nothing really.

Adam Back, the developer of key elements that ended up being used as parts of the Bitcoin system, was highly skeptical throughout this early period of development. The following is from a comment he left under the above post:

I was still hoping for the discovery of more efficient solutions…I was also thinking bitcoin was a 1 in a million chance that it could bootstrap to a non-toy value. So I did not download, nor mine at that time…So despite inventing the mining function that bitcoin uses, and spending a lot of research effort over perhaps 5 years on and off with others like Wei Dai, Hal Finney, Nick Szabo and a cast of dozens including anonymous contributors (one of whom may have been Satoshi) in trying to figure out how to design a decentralized ecash system using hashcash as a mining function, I didn’t wake up until years later when it was clearly obvious that bitcoin had long bootstrapped.

In the early days, even experts in the relevant fields, let alone anyone else, could easily have viewed mining bitcoins as a fairly pointless activity. It would have been easy for outsiders in particular to dismiss it as not much different in principle from a glorified version of the online social game Farmville. The difference was that it was as if a few of the players were also convinced that they had discovered the future of real farming. This just makes it sound even more ludicrous than just admittedly playing a game.

In farm games, untold numbers of people are known to “pointlessly” plant seeds using their computers. They eagerly check back later to harvest the resulting crops. These unreal objects can become quite meaningful to players after spending tens or hundreds of hours building a thriving (non-existent) business.

Yet even such play digital items must also be counted as goods according to the strict Misesian approach to economics, which studies action as such. As a field, economics in the Misesian tradition is not supposed to objectivistically judge whether certain actions are “rational” and others not, certain actions “economic” or “moral” and others not, and so on. Those are tasks reserved for other fields, such as philosophy or psychology, with different methodologies and criteria. Goods that exist only within games are also goods from the point of view of those engaged in playing those games and expending time and effort to obtain those goods.30

All of the non-existent seeds and produce in farm games, some critics might argue, are “really” just so many ones and zeroes on a computer, as are, they allege, bitcoins. Yet would the proponents of this view acknowledge that the difference between one digital film and another, or one song file and another, is likewise reducible to interchangeable ones and zeroes?

Try telling someone engrossed in an action movie or a favorite sports match that it would “really” be just the same if they switched to a Hello Kitty video or a match of some foreign sport they detested. Now take a tween’s pop music and grandpa’s classical concert playlists, switch them, and see what happens. The reality of meaningful distinctions among “mere ones and zeros” when it come to digital goods will have been convincingly established (if the experimenter manages to survive to report the results).

Some of the early Bitcoin miner/experimenters, at least those who believed the system had a future, accumulated bitcoins, just in case their value would somehow rise in the future. For participants, after starting, it may at times have been easier to keep the coins than to get rid of them. While some kept them safe, though, other early miners erased wallet files that conveyed access to large numbers of bitcoins. Others did not consider it worth even starting. They were convinced that nothing would ever come of these particular units in the future. Each of these were distinct judgments, valuations demonstrated in action.

Many systems were out there hoping to succeed as some kind of new digital cash—and failing at it. Experts could not universally predict that this new one would take off. Its success began with a new combination of ideas, but its success had to be defined through experimentation and discovery in practice. If one’s purpose had been to trade or buy goods or services with Bitcoins in their first year or two, then they were utterly useless. Yet they nevertheless had already gradually come to play various roles in the action structures of some early experimenters.

This is the moment the origins component of the regression theorem seeks to “regress” back to. This was a time when bitcoins had some value to some people, but going out and buying something with bitcoins—facilitating trades with them—was not among the available uses. At that time, it might have been easier to trade steak directly for flour with one’s ovo-vegetarian neighbor than to obtain anything whatsoever in trade for Bitcoin.

This condition, in which there was some value to some actors, but zero indirect-exchange value, was about to start changing. Although the regression theorem is a logical deduction from definitions, for those who like historical illustrations of their theoretical principles, Bitcoin provides a documented textbook example.

12. The first emergence of Bitcoin prices for money

On October 5, 2009, nine months after the Bitcoin network went live, the first recorded Bitcoin offer price was posted. It amounted to 13 bitcoins for a penny, specifically, 1,309.03 Bitcoins for a dollar, which the poster calculated based on his variable mining costs.31

A few months later, on 22 May 2010 was what is believed to have been the first use of Bitcoin to purchase a “real” market good at a cost of 10,000 Bitcoins for 25 worth of pizza.32 In reality, another party facilitated a pizza purchase by accepting Bitcoin and paying for the pizza with a credit card. The fame of the “Bitcoin pizza” transaction, while an important symbolic milestone, is just barely an exception to the generalization that Bitcoin was not used to purchase goods or services at the time. Rather than simply facilitating buying a pizza as such, it can be read more as an occasion to sell 10,000 Bitcoins to someone who paid 25 by credit card, and as it so happened, the $25 was directed toward the pizza provider rather than to the Bitcoin seller.

However it is characterized, the equivalent value was $25 for 10,000 bitcoins, or four bitcoins for a penny, a threefold increase over the first-ever quoted price a half-year earlier. This was one fledgling quasi-indirect exchange transaction (and can just barely be counted as that) using Bitcoin, probably done partly in jest, 16 months after the network went live. Clearly, Bitcoin did not just jump to life as a functioning currency.

Several months later, on 17 July 2010, the first recorded public exchange transaction for Bitcoin on the new MtGox exchange carried a price of 0.05, which climbed to a 0.06–$0.09 per bitcoin range over the coming days.

What may be difficult to grasp is that due to the digital nature of bitcoin units, their nearly zero transaction costs, and extreme strengths on several major characteristics valuable for medium-of-exchange use, the beginning of any exchange value, no matter how tiny, could be enough to help get trading of these units started. And start it eventually did.

Once some transactions began, and the first companies began to accept Bitcoin in payment for “real” goods and services, further expectations of a future medium-of-exchange value component could also begin to build—within the relevant groups of users. As more people witnessed the strange pioneers actually using the system to interact with real things, what once had been only an experiment began to make tentative interfaces with the wider exchange economy. This only becomes unmistakable in the historical record in 2011.33

Only a few people, and then a few more, had to take marginal steps in this direction, and others to eventually imitate them, year after year. Carl Menger described, in 1892, the processes that thus began and which continue to accelerate up to the present:

There is no better method of enlightening any one about his economic interests than that he perceive the economic success of those who use the right means to secure their own. Hence it is also clear that nothing may have been so favourable to the genesis of a medium of exchange as the acceptance, on the part of the most discerning and capable economic subjects, for their own economic gain, and over a considerable period of time, of eminently saleable goods in preference to all others.

In this way practice and a habit have certainly contributed not a little to cause goods, which were most saleable at any time, to be accepted not only by many, but finally by all, economic subjects in exchange for their less saleable goods; and not only so, but to be accepted from the first with the intention of exchanging them away again. Goods which had thus become generally acceptable media of exchange were called by the Germans Geld, from gelten, i.e., to pay, to perform, while other nations derived their designation for money mainly from the substance used, the shape of the coin, or even from certain kinds of coin. (Menger 2009, 37)

Bitcoins offer at least several compelling competitive advantages over other options:

- They are an inherently apolitical global unit without respect to borders. Potential direct trading partners over the long-term therefore include the entire human population from the barista on the corner to the grower direct-shipping fresh coffee beans from halfway around the world.

- They are infinitely durable in time and (almost) costlessly transportable in space. They could last potentially forever (for any practical purpose) with zero degradation. Like beads and metals before them—except more so—access to them can easily be carried, or even just remembered, so they can be hidden during times of threat.

- They have scarcity characteristics superior to all other known monetary alternatives. The limitation of their supply is built into their definition. This approach is superior to limitations anchored merely in the practical and variable supply of some chemical substance such as silver. They are even more obviously superior when compared with the proven record of inflationary machinations on the part of carefully screened political appointees in charge of fiat money supplies.

- They offer transaction costs that are almost infinitely small from the point of view of users, and this goes for any amount over any distance.

- They cannot be counterfeited, diluted, or multiplied, unlike paper notes and metallic coins.

With such a wholly unprecedented line-up of monetary characteristics (among others), any launching-point trading value could have been enough to get such extraordinarily well-suited units to begin acquiring a medium of exchange value component among some users. Being first among modern cryptocurrencies to make such a leap, Bitcoin has remained far ahead of later imitator coins based on first-mover advantage, network effects, and aggregate network hashing speed, becoming, and remaining by a massive margin, the most “saleable” of all existing cryptocurrencies.

The medium of exchange value component of bitcoins is now clear and dominant in retrospect. Like a new kind of metal dug up one day many thousands of years ago, its value profile in society emerged gradually from seemingly nothing. Its exchange value then moved all the way up to…nearly nothing. It then moved up to…slightly above nearly nothing. And finally it has been gradually building over the past three–four years with a few dramatic jumps along the way, as widening circles of social recognition come into play.34

Yet no matter what its current value is relative to other currencies, it can continue to fill a role as an almost zero-cost method of transmitting purchasing power over distance for any given transaction. Users opting for services that convert into and out of Bitcoin immediately for each transaction can be entirely free of exchange-rate risk, while other users choose to take on such risks knowingly in the expectation of short or long-term gains. A possible future role for Bitcoin as what I have defined as a money (a unit of pricing, accounting, and economic calculation) would have to await much more relative value stability compared to competing options for those functions.

However, it should also be emphasized that value growth, as contrasted with the steady value decline of fiat money, is an advantage separate from stability per se. Some people might rather have the option of holding some balances in units that gained value unsteadily, in contrast to balances of other units that lost it steadily.

13. Distinguishing the early value components

The early Bitcoin pioneers were attempting to create a functioning system of value transmission that contained units to be used as a medium of exchange. Despite this hope, for at least 2009, and the evidence suggests also 2010, they had not yet succeeded. Bitcoin was not used as a medium of exchange. Whatever their dreams or future imaginings, indirect exchange transactions were basically not facilitated using Bitcoin.35

Bitcoin units, however, did make their way into the action structures of these early users in various ways. They were the objects of action both directly and indirectly as “bundled” with other ends, such as the goals of system refinement, mining development, and project participation. That makes them goods (means toward ends, in Misesian terms).

To summarize, some mix of the following _non-_medium-of-exchange value components of bitcoin units existed for some users in a period during 2009 and 2010 before Bitcoin operated in any monetary medium-of-exchange role whatsoever. This was after Bitcoin began to exist and gain some value to some actors within their respective structures of ends and means, but before it began to have any value component for use in facilitating indirect exchanges for other goods and services.

The relevant persons were the pioneers actually participating in the Bitcoin network, contributing to the early refinement of its software and other technologies. Later, some additional participants purchased bitcoins (as highly risky financial investment instruments) with cash just in case the units might become worth something in the future. Bitcoins may have functioned in any of at least several possible non-monetary ways:

- A set of digital objects that could become a medium of exchange in the future if the network were somehow successful and if its units eventually began to be taken up as a medium of exchange. Any new class of valuable good is recognized and valued first by only very few people, often before it has any “practical” use. Many such goods never amount to much, but others take off and are eventually valued broadly.

- A set of digital objects that could be sent back and forth to other participants as a form of formal or informal testing of the network, or even as a type of social interaction within the project. Many of the project interactions took place online at distance over forums, and in some cases the participants were pseudonymous.

- Blocks were being mined, one of the purposes of which was to verify transactions. With no transactions to verify, network testing and experimentation processes would have remained incomplete, providing a reason to issue transactions at some points into the network even if only for the purpose of experimentation and testing.36

- At some points and for some persons, bitcoin units could have functioned as a toy-like set of digital objects that could be collected incidentally or even competitively in the course of the above processes of experimentation. This could be akin to how people naturally enjoy competing by accumulating and comparing different amounts of digital money or points within games, independently of any “real world” valuations. It would then be an extra bonus if an eventual real world value also really could emerge, as in (1).

- Possession of greater or fewer numbers of bitcoins could be taken as a badge of membership and commitment, or as among the signs and artifacts of participation. Possible non-exchange-media interests could have easily included: theoretical and scientific interest, programming challenge, security research, ideological interest in advancing the freedom of transaction, and interest in the possibility of making a rising-value currency available for the first time in a century to those who wished to have the option of using one. Membership and promotion motivations are common in human endeavors, present whenever we say that someone is “getting behind a cause.”

- A form of early stock-like ownership in the (potential) payment system that would convey the ability to participate in it more favorably in the future and help promote it from an early stage onward. This metaphorical investment share in the entire system also creates a tiny, direct incentive to act in a way favorable to the system’s general health. The early participants all invested their time and effort on an individual and voluntarily basis.

Some of these non-medium-of-exchange values of bitcoin units, or descendants of them, persist to this day among some system participants. These include: long-term retention of Bitcoin balances as savings (often derided as “speculation”); efforts to spread the word and introduce others to Bitcoin on both individual and institutional bases—including giving out small amounts of Bitcoin to new users—which broadens the network of users and applications; efforts to promote freedom of transaction and freedom from “financial censorship”; and educational efforts to explain the general economic advantages of the availability of a rising-value trading unit for those who wish to use one.

14. Chalk this one up for the crazy ones too

The process by which Bitcoin’s value for use as a medium of exchange emerged has been documented and archived in online records and in living memories. Bitcoin’s beginnings serve as an illustration of the origins aspect of the regression theorem that is similar in principle—though of course not in specific form, geographic configuration, or time scale—to market-evolution accounts interpreting processes by which previous tangible media of exchange emerged.

That is, in each such case we have considered, a few of mankind’s “crazy ones”37 were playing around with and collecting things that were useless for anything that would have been considered a generally “practical” purpose at the origin phases in question, such as shell beads, shiny metals, or bitcoins. Eventually though, an additional economic use for these mere trinkets—actually using them to facilitate trades—was gradually and in fits and starts put into practice, with some favorable results. This practice then spread by some blend of imitation and recurring independent rediscovery.

Such experiments were quite likely met in every case with furrowed brows and disbelief on the part of more sober observers still unwilling to trade “real” things for the likes of shells, shiny soft metals, or in the current case…they do not have the faintest idea what. The difference is, today, the process of more and more people discovering how to make use of Bitcoin to facilitate trade is taking place worldwide and at the speed of the internet and word of mouth.

That Bitcoin’s inventor(s) and earliest developers intended the network to be used for this purpose may be confusing for some people in light of general characterizations of market phenomena as being “emergent” and “the result of human action but not of human design.” It might remind them, vaguely, of the quite different state-theory-of-money story of “fiat” imposition by a ruler. It could even remind some of a complex con in which skilled scammers push out worthless shares in their latest scheme.

However, Bitcoin had no legal status whatsoever as it was being born. This makes it as distant as possible from a central “fiat” imposition through some official designation or fixed exchange rate. Even years after launching, conventional legal systems are only beginning to try to figure out how to categorize it within existing bureaucratic classification schemes.

Users are not compelled to adopt Bitcoin. People have not even much been pressured to use it by clever sales people making up stories. Although there have been a few specific pyramid scammers and outright thieves in the Bitcoin world, their scams were not Bitcoin, their scams were their scams. Those scams happened to be denominated in Bitcoin in those particular cases, but similar cons have involved all manner of other valuable units throughout time.

Bitcoin was offered up as an invention/discovery of a new way to do something very old—transfer the control of purchasing power from one party to another. This method was offered for free to the entire human population. However, people still had to take it up and put it to this use. Each person remains entirely free to either ignore it or use it in some way, and only to the exact extent of each person’s willing participation.

The intentional invention elements probably do help explain why Bitcoin is superior to any known alternative medium of exchange on just about every meaningfully relevant characteristic (tangibility being an incidental historical one, I have argued). Should a broad-based and overwhelming competitive superiority for a given purpose be a disqualifier for that purpose? That would be odd indeed. Yet someone already familiar with the theoretical aspects of the emergence of money could take, and seems to have taken, those very insights into consideration in trying to shape a better good for use in that role.

Nevertheless, we have still seen that there remained a vast gap between the implementation of the intentional elements behind the new technically produced digital good and the subsequent gradual phases when people began tentatively putting this strange new good to use for some of its envisioned functions. In other words, there was a large gap between the launch of the open-source, peer-to-peer network (technical layer), and the time when bitcoin units actually did begin being used in trade (economic, or more precisely, “catallactic” layer).

There was a purely technical and experimental phase in progress well before there was any uptake of the unit/system for monetary use in society. During this early phase, it was unclear even to inside experts whether or not the project would either succeed technically or gain any monetary traction. The eventual achievement of a $1 price was cause for a huge celebration at the time among early enthusiasts, along with a little profit-taking by some pioneer miners.

Bitcoin’s emergence as a medium of exchange was original, as with beads or metals in the past. It was not derivative, with monetary values taken over from tangible forerunners, as with the history of modern paper tickets and fiat digital account entries.

At the same time, Bitcoin is a novel case. Its scarcity has been achieved without tangibility. It was not picked up at the beach and carved, nor was it dug out of the side of a mountain and cleaned or melted. It was built out of the intricacies of new cryptographic and computer science innovations that were remixed and put together in a new and valuable way. Bitcoin is dug out the side of crypto-cyberspace mountain. The first hit of a pickaxe on this never-before-seen ore was heard on January 3, 2009.

Satoshi Nakamoto set this network in motion in the context of tremendous work and overlapping complex innovations on the part of many others both before and since the initial Genesis Block timestamp. It was up to the test of time to see if what was begun would continue. It was up to the free choices of the rest of humanity who would take up these units and start to use them as a new medium of exchange.

It was unclear whether, or the extent to which, anyone would “buy into” both the units and the idea of using the novel payment protocol in which they are embedded. This is probably much more similar than might at first be imagined to the thought processes of a few skeptical hunter-gatherers or early agriculturalists taking a deep breath and finally accepting for the first time some strings of beads or pieces of shiny soft metals in trade for “real” goods.

No decree or command causes people to begin trading in Bitcoin. Nor has adoption resulted from some clever sales pressure taking advantage of the uninformed. In diametric contrast, the more informed that people are about the technical underpinnings of Bitcoin, the more they tend to appreciate it. Meanwhile, casual dismissers generally seem to display little to no technical comprehension of how the system works.

Bitcoin gives us a textbook illustration of Mises’s praxeological statement of the regression theorem. It provides an empirical case study that has been documented at a level of detail never before seen. If so moved, researchers in the field of economic history could still personally interview almost everyone who was involved in every stage of this process (except the wisely elusive inventors), a project that Peter Šurda has already been advancing.

Our earliest shell-bead traders from tens of thousands of years ago are not likewise still taking interviews. Bitcoin may well be our best-documented historical case of the first origins of an entirely new medium of exchange on the market, free of the dictates of any ruler.

Appendix A: Monetary interpretation by year