The Risk from the Software Industry

Chapter 2: Public-Key Cryptography

Chapter 3: The Killer App of Liberty

The Government Attack

As wonderful as it is, public-key cryptography can be subverted and even turned against us. It is subverted when our computers cannot keep them secret, and it becomes a tool of oppression when we are issued private keys in a way that prevents us from seeing them.

The first of these attacks is performed either by remotely controlling our computers with a virus that is secretly installed on it or tricking us into installing ourselves, or by altering our computers so that all data is stored on some remote server rather than a hard drive. The second attack is done by giving everyone computer chips with private keys inside them. This could be in form of an ID card with an RFID chip inside or as a computer with a Fritz-chip attached.[1]

The first attack prevents the formation of cryptographic communities, and the second alters the nature of a cryptographic community so that it is no longer empowering to the individual. An ID card with an RFID chip on it not only may be demanded by the police on their own whim rather than that of its’ owner, but it cannot even be forged.

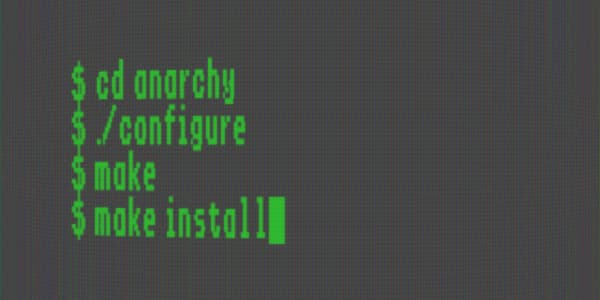

Combining these attacks results in the Orwellian monster known as Trusted Computing. Under this model, a computer comes with a Fritz-chip attached on which is hidden a private key, and with software installed that depends upon it to run properly. When the computer boots, the Fritz-chip detects if the computer is in a trusted state, meaning that restricted operating system has not been replaced by something else and refuses to decrypt anything otherwise. This prevents the user from installing software to avoid the restrictions built into the operating system. Software companies can design restricted file formats that cannot be read by competing software packages or which only work on certain peoples’ computers rather than others. The operating system can be designed to detect and prevent certain activities, such as file sharing. The totalitarian possibilities of such a system are in Richard Stallman’s terrifying and prophetic tale, “The Right to Read.”

As nightmarish as it is, Stallman’s tale does not go far enough. In his story, computers are all restricted by law according to the interests of a media-software cartel. No doubt any government would happily be manipulated for such a purpose, but once the power was available, its use would spread to serve other interests too, such as that of the police. The government might, say, install an artificial intelligence program on everybody’s computer to detect and report subversive literature or evidence of tax evasion to police. It could try to automatically delete Bitcoin wallets and block Bitcoin transactions. They could make your computer download and install regular updates to keep your computer up-to-date in blocking the latest subversive techniques.

This may seem far-fetched. Today it appears that we have won the battle on file-sharing. Media companies are even beginning to incorporate file sharing into their business models. This is no reason to be complacent because other attacks are in the works. Now it is illegal to root your own phone under the DMCA. Although DRM is not yet required by law, most computer manufacturers already make computers with Fritz-chips attached.[2] The computer industry is ready. Once a law does go into effect, we will be confined. The FBI has lobbied for a law that would require back-doors to be built in all security services. Although this proposal has been watered down from its original version, it can be expected that they will continue pushing for more and more draconian measures.

Furthermore, consider the criteria I gave in chapter one for evaluating the risk of an industry to government attack.

- It is obvious that any government would consider communication to be a high-priority industry. The fourth amendment is still theoretically in effect in the USA, but the government has merely to collude with computer manufacturers, service providers, and software companies, to access your data through them without a search warrant. It can use this strategy to censor the internet as well.

- The software industry is highly centralized, not in the sense that a single company produces nearly all the software, but rather that there are some software packages that are used by most people. If Microsoft, Apple, Google, and Facebook, were all corrupted (which they already are) nearly all computer users would be affected.

- The software industry promotes dependence. It is very difficult to switch from Windows to iOS, for example. So difficult, in fact, that people people cover up for their dependence on Microsoft or Apple by developing irrational loyalties to one brand so as to make it appear as if they continue to choose their favorite brand for reasons other than an inability to leave it.

As yet the government does not appear to be pursuing a deliberate policy of cartelization, but as these companies lobby their way into privilege through software patents and legally enforced DRM, the government may eventually find itself in the position of having the internet within its grasp. This is why computer manufacturers and the software industries should be seen as high-risk. The service provider industry is also at risk, but if we can retain control over our devices and software, then its threat will have been mostly eliminated as well.

Free Software and Libertarian Strategy

Libertarians know to fear the banking industry because we know from history what is possible with a government banking cartel. The computer and software industries should be even more feared. This is not merely a problem with individual companies. It is a problem with standard business practices. Although libertarians complain about how Microsoft crushes smaller companies with their use of patent monopolies and how Facebook shares information with the FBI, I have observed little awareness among libertarians of the correct solution. Perhaps we are so dependent upon these companies and so used to their business practices that to state the correct answer is such an annoying prospect that we would rather just wish there were an easier way.

But there is really only one defense: to retain control over our computers, our software, and our data. The standard business practices today demand that we give up control. This is so normal to most of us that it is hard to imagine what it would really mean to retain control.

Fortunately, the necessary philosophy was developed by Richard Stallman, founder of the free software movement and of GNU, a project to create a free operating system that eventually evolved into the GNU/Linux.[3] Free software is software whose source code is as available as its binaries and which comes with the right to edit and redistribute edited versions.[4] This term refers only to the rights that come with the software, not to its money price. Proprietary software is software that is not free software. The major goal of the free software movement is that all software should be free software.

Libertarians have not had much of a connection with the free software movement before. I would rate it as at least as important an ally to the libertarian movement as the homeschooling movement. There is much that is admirable about it: Stallman, for example, was against copyright and patents long before libertarians got the picture. He invented copyleft, which, though not entirely compatible with libertarianism, is, as a form of self-defense in a world oppressed by intellectual property, a stroke of genius.[5]

What is relevant now, though, is free software as an essential component of libertarian entrepreneurship. When we use free software, we depend on a community of developers who work on the program because they actually want to use it. When we use proprietary software, we depend on specific companies. We, furthermore, give up control: when we use proprietary software, we can still smash our computer but we cannot know what it is doing while it is still running. There is nothing but a promise that it is behaving as it is supposed to, without any means of verification, and the considerable possibility of a conflict of interest. This is like trusting a politician. Whereas with free software, even without being able to read computer code, someone can give you an informed opinion about it. Everything has independent verification.

Proprietary software is inherently a security risk. This applies not only to programs with security functions, like operating systems or encryption software. It applies to every program running on your computer: there are the obvious kinds of viruses that exist for no purpose other than to hijack computers, but there are also the viruses which have legitimate purposes and which people voluntarily pay for and install and which actually do a good job at what they are supposed to do, but which are, nonetheless, still viruses.

Yet any program could have this property, and many do. Operating systems in particular tend to come full of malicious features. The Amazon Kindle, iOS devices, and Android devices are all known to contain kill switches that allow their manufacturers to delete apps and files remotely. In a particularly ironic example, Amazon.com once deleted Nineteen Eighty-Four from everyone’s Kindles in response to copyright issues. Windows 8 now comes with a kill switch as well, thus making it the first desktop operating system that allows for remote control from a big software company.

Even a seemingly innocuous program like Flash player can turn out to be risky. Few people are aware of the danger of flash cookies, but most big websites use them to track us without our knowledge or consent.

Malicious features make your computer more vulnerable to software companies, hackers, and to government-software collusion. If all software were free software, it would be much easier for people to choose not to be vulnerable. As a matter of libertarian strategy it is not necessary that all software be free, but certainly to be much more than there is now, enough to leave the government with little to gain from a software cartel. It is incredibly reckless that there should even be such things as proprietary operating systems and web browsers, for example. It is obviously also necessary for any cryptographic software to be free.

Another way we give up control is when we do our computing remotely. When we use services like GMail or Facebook, it is not enough to blame the companies behind them for cooperating with the police. We should also blame ourselves for being such easy targets. We cannot know what sort of computations are being done with it. We give up our information such that it is no longer up to us to decide whether to show it to the police without a warrant. As Richard Stallman points out, the government already encourages software-as-a-service for this very reason. I have not heard this connection repeated in libertarian circles, even though it seems like something libertarians should have figured out on their own. Both software-as-a-service and cloud computing must be rejected as inconsistent with a viable strategy for liberty.

Finally, the third way we give up control is to use proprietary devices. A free device is one that does not arbitrarily restrict the user’s ability to install software of his own choosing on it. A proprietary device is, of course, the opposite. I have already discussed how many operating systems come with kill switches and other remote-control features. Combining this with a proprietary device results in something whose malicious features cannot be removed.

To retain control over our computers, we must drastically reduce proprietary software, proprietary devices, and software-as-a-service as business practices. Libertarian entrepreneurs should try to compete with other business practices that make our computers more secure against outside control. This will greatly reduce the risk of a government invasion of our computers and the internet.

Free Software and Voluntary Slavery

I do not think there is anything wrong in principle with the concept of voluntary slavery,[6] but I would not want to live in a world where it was the accepted norm. Not only would such a society be unlikely to present me with acceptable opportunities to fit my own personality, but such a system could easily evolve into one of involuntary slavery because the tools of mass repression would necessarily exist. Voluntary slavery should be seen as an issue of libertarian strategy rather than libertarian principle.

The issue is relevant because a person whose computer is restrained is not literally in chains, but it is as if he were. The difference is only one of degree. The distinction between our body and our devices is only a matter of our limited technology. Some day it will be possible for our bodies to be products as much as our devices. We may connect our computers directly to our brains. They might be used to enhance our thoughts or control our vehicles (thus incorporating them into ourselves as well). These hypotheticals, which blur the line between body and devices, show that the distinction between them is not conceptual, but merely empirical.

Already people depend on their computers so much that they are getting to be like body parts. Our computers are a conduit to the rest of the world. They are our eyes, ears, and mouth. Thus, I do not consider myself to be speaking hyperbolically to say that a person who buys an iPhone becomes a voluntary slave. He uses the device as his eyes and ears to the world and he does not even have the right to say what software he wants to install on it. Apple retains the ability to remotely control his device, so at any moment, Apple might shut off his vision, send him hallucinations, or secretly watch him.

Free Software Values

GNU/Linux does not yet have enough popular appeal. It appeals to people who like to program, people who don’t want to give up control, or people who understand its technical superiority. Most people are in none of these categories. Although it is the foundation for many devices, the philosophy behind it is not. Android is a version of GNU/Linux, for example, but the devices that run it have restrictions to prevent the user from gaining root access. Thus, they are not free devices.

Promoting free software values is about as difficult as promoting libertarian values because they, too, are very abstract. I do not know how to convince people to become excited enough about programming to worry about free devices. However, I think it is at least possible for libertarians to adopt free software values. Although the nonaggression axiom does not require anyone to own a gun, I think that most libertarians would sleep better knowing that their neighbors owned guns and knew how to use them. However, in today’s world it would make more sense to worry about whether their neighbors used GNU/Linux.

One hope now is that Wikipedia is has become ubiquitous. Thus by analogy people can understand the advantages of software that is built according to a similar model. However, it is only once people people actually could actually exercise control over their computers that they will want to retain it. Unfortunately, we live in an illiterate world. Perhaps one day that will change. Programming ought to be seen as an essential component to a liberal education, as much as science, mathematics, or literature.

Conclusion

When I first became a libertarian, I wondered how we would ever win enough elections. When I came to understand that this is impossible, I wondered if there was anything we could do at all to prevent a decline into fascism. Now I no longer wonder. The way out is entirely within our means.

But the world still hangs in the balance. People are blundering along the path to slavery. Libertarians are not doing enough to help; most are blundering along with everyone else. Some libertarians, with breathtaking foolishness, even reject Bitcoin.

My prescriptions are simple: promote Bitcoin and oppose proprietary software and proprietary devices. These will greatly diminish the risk imposed on us from the banking and financial industries, and from the software and computer industries. If you are a coder, improve cryptographic free software, such as Bitcoin, Tor, or RetroShare. Above all, however, is to keep the mind open for new ideas. Search for government risks that have not yet been addressed. Search for new services that can be provided by cryptographic communities. Stay one step ahead of the government and don’t get embroiled in politics.

See Anderson, R., “‘Trusted Computing’ Frequently Asked Questions”, Jul 2003 and Stallman, R., “Can You Trust Your Computer?”, 28 Feb 2013 for discussions of Trusted (Treacherous) Computing. See Wikipedia for a more neutral explanation. ↩︎

Wikipedia, “Trusted Computing Platform”, Wikimedia Foundation, 6 May 2013. ↩︎

See Stallman, R., “The GNU Project”, 28 Feb 2013 for a history of the GNU Project. ↩︎

See Stallman, R., “What is Free Software”, 28 Feb 2013 for a much more detailed description. Also see Stallman, R., Free Software, Free Society: Selected Essays of Richard Stallman, GNU Press, 2002 for a wonderful collection of essays expounding upon the philosophy of free software. ↩︎

See Stallman, R., “What is Copyleft?”, 28 Feb 2013 and Stallman, R., “Freedom or Power”, 28 Feb 2013 for Stallman’s views on copyleft. ↩︎

See Block, W., “Toward a Libertarian Theory of Inalienability: A Critique of Rothbard, Barnett, Smith, Kinsella, Gordon, and Epstein”, vol. 17, no. 2, Journal of Libertarian Studies, 2003, pp. 39-85 for a libertarian defense of voluntary slavery. See Kinsella, N., “How We Come to Own Ourselves”, Mises Daily, 7 Sep 2006 for a libertarian argument against it. ↩︎