Chapter One

Bitcoin Obsoletes All Other Money

Originally published

on 24 January 2020

One Thousand Possibilities, 999 Problems

There are two rules that never seem to fail when it comes to bitcoin adoption. Everyone always feels late, and everyone always wishes they had bought more bitcoin. While there are exceptions to every rule, bitcoin has an uncanny ability to screw with the human psyche. It turns out that 21 million as a nominal currency supply is a very small number. And it is a number that becomes ever smaller as more individuals adopt bitcoin, which occurs as more people figure out that bitcoin’s fixed supply is credibly enforced and that economic systems converge on a single form of money.

Demand for bitcoin is driven by the credibility of its monetary properties and the convergent nature of money. As more people adopt bitcoin, there is increasing competition for a resource fixed in supply, which causes bitcoin to become more and more scarce. As it does, bitcoin becomes more valuable as a monetary medium. While this becomes evident the further one travels down the bitcoin rabbit hole, it is not uncommon for individuals on the periphery to be overwhelmed by the sheer number of cryptocurrencies. Sure, bitcoin is in the “lead” today, but there are thousands of others. How do you know bitcoin is not Myspace? How can you be sure that something new doesn’t overtake bitcoin?

It may sound crazy to believe that bitcoin will become the dominant global currency if you’re evaluating the possibility from a top-down, probability-weighted perspective. Today, bitcoin is one of more than a thousand digital currencies that all look the same on the surface. Its current purchasing power of $150 billion (as of the time of writing), is a drop in the bucket compared to the global financial system, which supports $250 trillion of debt. Gold alone has a purchasing power of $8 trillion (50 times the size of bitcoin). What are the chances that an eleven-year-old internet sensation rises from the ashes of the 2008 financial crisis and goes from nothing to becoming the dominant global currency? The idea sounds laughable. Or at the very least, it appears to be too low of a probability to warrant consideration.

Evaluating one thousand possibilities in the hope of coming to the right solution may not be practical or possible. However, when taking a bottom-up approach and developing conviction around a few foundational principles, it becomes more practical to arrive at a coherent answer. Combined, the following foundational principles bring simplicity and clarity to what may have once seemed too complex to possibly discern.

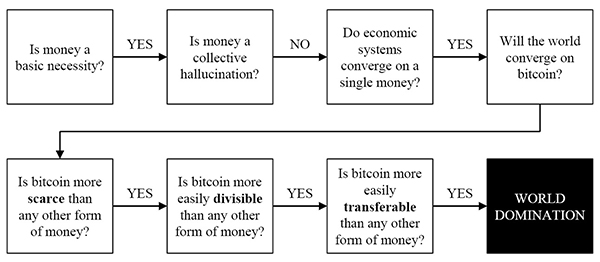

This roadmap is critical and will help you cut through the noise and focus on what really matters. Individuals may come to different conclusions concerning any of these questions, but this is the path to consider when attempting to understand why bitcoin consistently outcompetes all other currencies (and whether it will continue to do so). Money is a basic necessity, but it is not a collective hallucination or a shared belief system. Individuals adopt bitcoin because it possesses unique properties that make it superior as a form of money relative to all other forms of money. Because money solves an intersubjective problem, monetary systems tend to converge on a single medium. Or rather, economic systems naturally emerge from the common use of a single medium due to the function of money. The properties inherent in bitcoin are causing the market to converge on it as a tool to communicate and measure value because it represents a step-function change improvement over any other monetary medium. If anyone comes to the fundamental conclusion that money is a basic necessity and that monetary systems naturally converge, the question then centers on whether bitcoin is optimized to fulfill the monetary function better than any other medium.

Money Is a Necessity

Civilization as we know it would not exist without money. There would be no airplanes, cars, or iPhones, and the ability to fulfill very basic necessities would become materially impaired. Millions of people could not peacefully inhabit a single city, state, or country without the coordination function that money enables. Money is the economic good that allows for food to reliably show up on grocery store shelves, gas to be at the gas station, electricity to be supplied to power homes, and clean water to be abundant. It is money that makes the world turn, and it would not turn in the way that most have taken for granted if not for the function of money. Money serves a massively underappreciated function and one that is poorly understood because it is generally not consciously considered. In the developed world, reliable money is taken as given. So too are the basic necessities delivered through the coordination function of money.

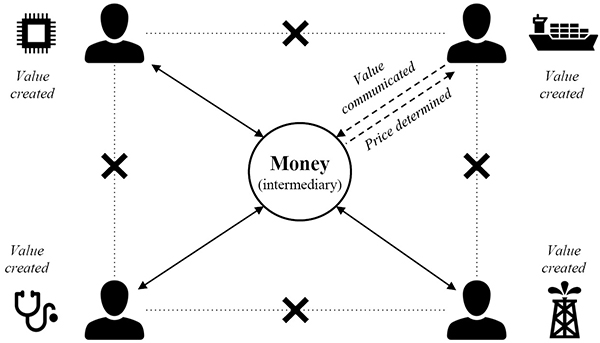

Consider, for example, a local grocery store and the range of choice that converges in a single place. The number of individual contributions and skills required to make that happen is mind-boggling, from the coordination of the store itself to the individual packaging, to the technology providers, to the logistics networks, to the transportation networks, to the payments systems, and right down to each item of food. Then, as a derivative, consider all the unique inputs that go into each item on the shelf. The grocery store is just the fulfillment side. The production of each input has its own diverse supply chain. And it is just one modern marvel. Deconstructing the inputs of a modern telecom network, energy grid, or water treatment and waste management system is similarly complex. Each network and the participants therein rely on the others. Food producers depend on individuals who help fulfill energy demand, telecom services, logistics, and clean water, among others—and vice versa. Practically all networks are connected, and it is all made possible through the coordination function of money. Everyone can contribute their skills based on their own interests and preferences, receive money in return for value delivered today, and then use that same money to acquire the specialized value created by others in the future.

None of this happens by chance. Some not-so-rigorous thinkers suggest that money is either a collective hallucination or derives its value from the government. In reality, money is a tool invented by man to satisfy a very specific market need. Money helps facilitate trade by acting as an intermediary between a series of present and future exchanges. Without any conscious control or direction, market participants evaluate various goods and converge on the tool best suited to convert present value for future value. Whereas individual consumption preferences vary from person to person and change constantly, the need for exchange is practically universal, and the function is distinctly uniform. For every individual, money allows value produced in the present to be converted into consumption in the future. The value one places on a home, a car, food, leisure, etc. naturally changes over time and varies among individuals. But the need to consume, exchange value, and communicate preferences does not change and applies to all individuals on an intersubjective basis.

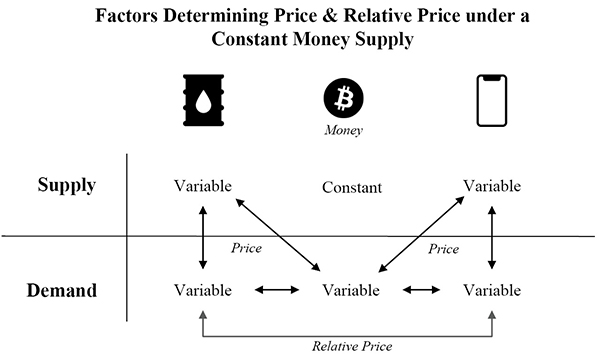

Money exists to communicate these preferences and, ultimately, to exchange value. But recognizing that all value is subjective (and not intrinsic), money forms the baseline to establish an expression of value and, more importantly, relative value. Money represents the collective recognition that everyone benefits from the existence of a common language to communicate individual preferences. The function of money aggregates and measures the preferences of all individuals within an economy at any point in time, and it would be practically impossible—or at the very least, extremely inefficient—to communicate or quantify value if not for a common constant upon which everyone could agree. Think of money as the constant against which to measure all other goods. If it did not exist, everyone would be at a practical standstill, unable to agree on the value of anything. Comparing against a single constant makes it more practical to discern the relative value of two other goods. There are millions of goods and services produced by billions of individuals, all with unique preferences. Through convergence on a single form of money, a price system ultimately emerges, without which standardized value could not be quantified. By measuring and expressing the value of all goods in a common intermediary (money), it then becomes possible to discern how much one good (or resource) is valued relative to any other.

Without a common currency, there would be no concept of price. And without the concept of price, it would be impossible to do any range of economic calculations. The ability to perform economic calculations allows individuals to take independent actions, relying on the information communicated through a price system, to best satisfy their own needs by understanding the needs of others. It is a price system that allows supply and demand structures to form. And a price system is ultimately a necessity because it provides for the communication of information, without which the fulfillment of basic needs would not be possible. Imagine if nothing you consumed had a discernible price. How would you know what you needed to produce in order to obtain the goods you value in exchange? Recognize that your own conception of the value you produce, and the very existence of goods and services produced by others, would not be available if not for some expression of price existing. It becomes circular, but money is the good that allows the underlying structures of an economy to form through the price system. While often lamented as the root of all evil, money may just be the greatest accidental invention ever created and one that could not have emerged by conscious control.

I have deliberately used the word “marvel” to shock the reader out of the complacency with which we often take the working of this mechanism for granted. I am convinced that if it were the result of deliberate human design, and if the people guided by the price changes understood that their decisions have significance far beyond their immediate aim, this mechanism would have been acclaimed as one of the greatest triumphs of the human mind. Its misfortune is the double one that it is not the product of human design and that the people guided by it usually do not know why they are made to do what they do.

Economic Systems Converge on a Single Form of Money

As a starting point, accept that two facts are true—the world previously converged on one form of money (i.e., the Gold Standard), and while there may be a few hundred fiat currencies in existence globally, virtually every individual and business in the world only transacts in one form of money on a daily basis. Neither is a coincidence, and both are deeply rooted in the nature of money. Even still, the phenomenon is not immediately intuitive, and late-stage Silicon Valley thinking has many people believing that hundreds, if not thousands, of currencies may exist in the future. The machines are going to do all the calculations! Artificial intelligence and quantum computing will handle it. An intellectually “safe” view to hold is that 95% of cryptocurrencies will probably fail, but there are some “interesting” projects. The logic mimics venture capital investing—it is inherently difficult to know which will succeed, and while most will fail, the ones that win will win big. At least, this is what most of Silicon Valley would have you believe because it is a defensible parallel to the historical experiences of investing in early-stage venture companies. In reality, it is a blanket hedge lacking in first principles. It also applies a familiar formula to an entirely different class of problem.

While it may seem logical to form a mental framework around bitcoin in relation to the rhyming history of technology startups, there can be no comparison whatsoever. Bitcoin is money, not a company. It would be illogical to assume competition between monetary mediums would follow a similar pattern to that of companies. Companies compete in a capital formation and capital accumulation arms race. To do so, they need money to coordinate economic activity. How do they get money? By using money to coordinate the production of goods and services and by selling the output for more money (profit). In essence, companies compete for the same pool of money in order to accumulate capital. Money is the tool that makes the wheel go round. It simply would not be possible to coordinate all the individual skills necessary to produce goods and services derived from complex modern supply chains without money. It would also not be possible if not for a large group of people accepting a common form of money.

Having a single medium of exchange allows the size of the economy to grow as large as the number of people willing to use that medium of exchange. The larger the size of the economy, the larger the opportunities for gains from exchange and specialization, and perhaps more significantly, the longer and more sophisticated the structure of production can become.

Value is created by individuals through the fulfillment of goods and services. However, the communication of this value is not direct. Instead, it is communicated through money as an intermediary. Money provides the baseline to express the very concept of value. Every time an individual converts goods or services into money, a price is determined or changed, and information is communicated. Price is ultimately the information, and money is the medium through which price is communicated and value is exchanged. While all other goods are non-fungible and variable, money is a utility because it provides a single, fungible constant that allows for the measure and exchange of value.

In the production supply chain, money serves a distinct function from all other individual goods or services. It is the distinction between the fulfillment of preferences (production of goods and services) and the coordination of preferences (money). The fulfillment of preferences is dependent on the coordination of preferences, and the coordination of preferences is dependent on a price system, which can only form as a derivative of mass convergence on a single monetary medium. Without a pricing system, division of labor would not exist, at least not to the extent necessary to allow for the functioning of complex supply chains. This is the root-level principle most miss when contemplating a world of many currencies. Any pricing system derives from a single currency. Convergence is a precursor. The concept of price (and relative price) would not exist if not for a critical mass of individuals producing a diverse range of goods and services and communicating the value of those goods and services through a common medium. As a result, it may be more accurate to say that economic systems emerge from the common use of a single monetary medium rather than converge on one. Individuals converge on a single form of money, and the output is an economic system.

Whereas the value of all other goods and services is in their consumption, the value of money lies in the utility of exchange. Exchange is the good an individual purchases when choosing to convert value (the subjective output of time, labor, and physical capital) into a monetary good. Individual consumption preferences are unique, but money serves one singular function for all market participants: to bridge the present to the future (whether it be for a day, week, year, or longer). In any exchange of present value, some time continuum exists until a future exchange. At the point of exchange, each individual must decide which monetary good will best serve the function of preserving value created in the present into the future. A or B? While an individual can choose to hold one or multiple currencies, one form of money will preserve future purchasing power better than the others. Everyone intuitively understands this and makes a decision based on the inherent properties of one medium relative to another. When deciding which monetary good to use, the preference of one individual is impacted by the preference of others, but each individual is making an independent evaluation discerning the relative strengths of multiple monetary goods. I must have the form of money you are willing to accept in order for us to trade and the identical problem extends out to every single person in an economy. It is not a coincidence that the market converges on a single medium because each individual is attempting to solve the same problem of future exchange—an intersubjective problem dependent upon the preference of others.

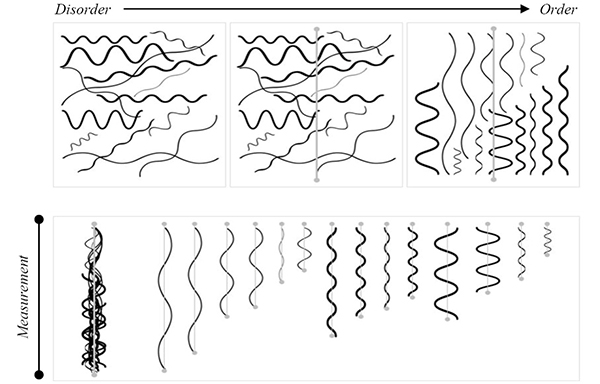

The ultimate goal is to reach a consensus so each individual can communicate and exchange value with the widest and most relevant set of trading partners. It is an objective evaluation of tangible goods based on an intersubjective need. The whole point is to find the one good that everyone can agree is (1) a relative constant, (2) measurable, and (3) functional in exchange. The existence of a constant creates order where none existed previously, but that constant must also be functional as both a measurement tool and a means of exchange. It is the combination of these characteristics—often described as aggregating the properties of scarcity, durability, fungibility, divisibility, and transferability—that is unique to money. Very few goods possess all of these properties, and every good is unique, with inherent properties that cause each to be better or worse in fulfilling certain functions within an economy. A is always different than B, and the combination of properties required for a good to be viable as money is so rare that the distinction from one to another is never marginal.

On a more practical level, everyone agrees on a single monetary good through which to express value because it is in their individual and collective interest to do so. That is the problem itself—how to communicate and trade value with other market participants. It would be counterproductive to the entire exercise if a consensus were not formed. However, a consensus is not reached randomly. The properties inherent to a specific monetary good cause a convergence and consensus to emerge. The imagined world of thousands of currencies is blind to these fundamental first principles. A critical mass of individuals converging on a common medium is the input required to ascertain the information and benefit that is actually desired: a price system along with the ability to trade. And the value of a common medium only increases as more and more people converge on it as a tool to facilitate exchanges. The fundamental reason is that as more individuals converge on a single medium, the medium accumulates more information and greater utility—more prices and more opportunities to trade.

Think of each individual as a potential trading partner. As individuals adopt the common medium as a standard of value, all existing participants in the monetary network gain new trading partners, as do those joining the network. There is mutual benefit to existing holders of the currency and new adopters that comes from increased adoption. As the monetary network expands, the range of choice also expands as more goods come to be denominated in and traded for the common medium of exchange. More prices exist, which enables more relative prices as a result. More information is aggregated into the common medium, which can then be relied upon by all individuals within the network (and the network as a whole) to better coordinate resources and respond to changing preferences via trade. The constant becomes more valuable and inherently more reliable as it communicates more information about more goods produced by more individuals. The more variable information communicated through the constant, the more constant it becomes relative to all other goods and services in aggregate.

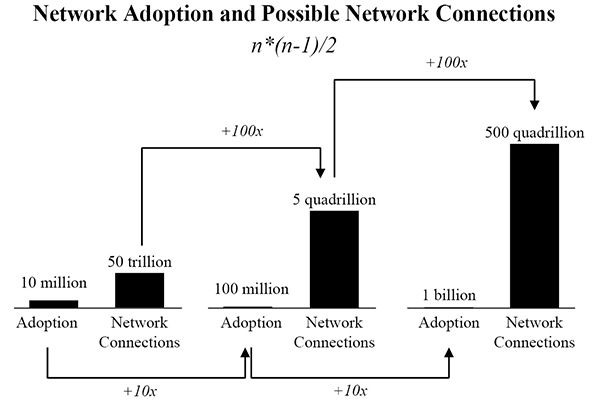

As the adoption of a monetary network increases by an order of magnitude (10x), possible network connections increase by two orders of magnitude (100x). While this helps demonstrate the mutual benefit of adoption, it also highlights the consequence of converting value into a smaller monetary network. A network one-tenth the size has only 1% of the number of potential connections. Not every network distribution is equal, but a larger monetary network translates to a more reliable constant to communicate information—greater density, more relevant information, and ultimately, a broader range of choice. The size of a monetary network and its expected growth become critical components of the intersubjective A/B test when individuals are determining which form of money to use. While the number of social relationships an individual can maintain is inherently limited, the same limits do not apply to monetary networks. Money is what allows humans to break from the constraints of Dunbar’s number (the theorized maximum number of interpersonal relationships one can reasonably maintain). A monetary network allows millions (if not billions) of people unknown to each other to contribute value at endpoints in the network, with relatively few direct connections needed.

Monetary networks ultimately accumulate the value of all other networks because all other network effects would not exist without a monetary network. Complex networks cannot form without a common currency to coordinate the economic inputs necessary to kick-start the positive feedback loops of price. A common currency is the foundation of any monetary network, allowing other value networks to form. It provides the common language to communicate value, leading to trade and specialization, and organically creating the ability to expand the use of resources beyond the reach of “conscious control” (to borrow from Hayek). When contemplating the network effects of a social network, logistics network, telecom network, energy grid, etc., add them all together—that is the value of a monetary network. It not only provides the foundation for all other value networks to form, but the currency pays for access to all derivative networks within the monetary network. The existence of a common currency is the engine and the oil.

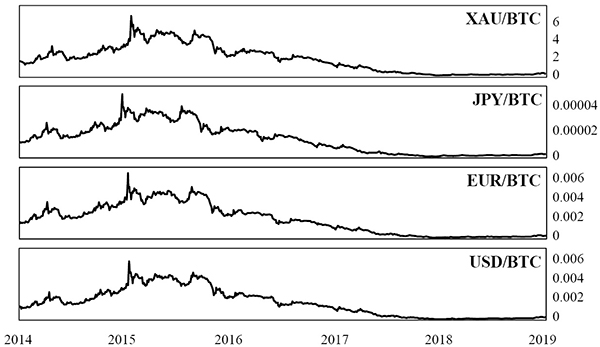

Admittedly, multiple currencies—the dollar, euro, yen, pound, franc, yuan, ruble, lira, peso, etc.—all coexist today. But this is not a natural phenomenon inherent to an open, global economy. Fiat currencies emerged as a fractional representation of gold, which the world had previously converged upon as a monetary standard. None would subsist without the forces of government intervention, nor would any fiat currency have ever emerged if not for the prior existence (and limitations) of gold—or the backing of another commodity metal—as a monetary medium. While modern monetary theorists and gold bugs alike will never admit it, the calamity that is all fiat systems is nothing more than the manifestation of gold’s failure as a monetary medium. It is a dead man walking. Following the formal abandonment of the gold standard in 1971, the subsistence of jurisdictional fiat systems merely represents a transient departure from free-market monetary forces. Modern fiat systems have only survived this long because a solution to the very problem created by fiat currencies did not yet exist. Bitcoin is that solution, and since its creation, individuals have been converging on it as a new monetary standard. It is a trend that will only continue as knowledge naturally distributes.

Source pricedinbitcoin21.com

All Roads Converge on Bitcoin

The Greatest Constant—Finite Scarcity

The market is converging on bitcoin over time, and its value continues to increase because it provides a constant—a fixed supply not susceptible to change—that is superior to all other forms of money. Bitcoin has an optimal monetary policy, and that policy is credibly enforced on a decentralized basis. Only 21 million bitcoin will ever exist—a fixed maximum supply that is enforced by a network consensus mechanism on a decentralized basis, eliminating the element of trust entirely. No one trusts anyone, and everyone enforces the rules independently. As an aggregate of these two functions—an optimal monetary policy that is credibly enforced without trust—bitcoin is becoming the scarcest form of money that has ever existed.

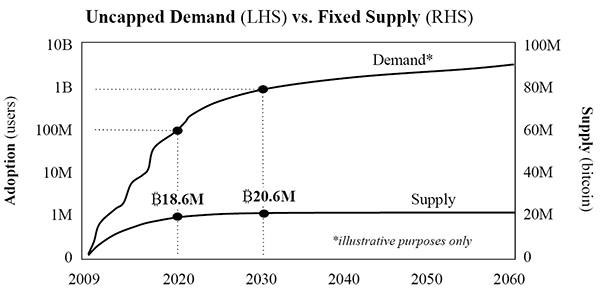

Finite scarcity is a property no other form of money has ever or will ever achieve, and demand for bitcoin is fundamentally driven by that scarcity. However, scarcity is a two-sided equation. A fixed supply may be the primary draw, but demand is a critical and often overlooked aspect of scarcity. Demand is what makes scarcity a utility as a constant in exchange. Bitcoin becomes increasingly scarce as a combined function of both increasing demand and a perfectly inelastic terminal supply. The scarcity of its fixed supply creates demand, but increasing demand creates greater scarcity. It sounds circular because it is. If there were 21 million bitcoin and only one person valued them, there would be nothing scarce or useful about bitcoin. But if 100 million people valued bitcoin, 21 million would start becoming scarce. And if the network grew to one billion people, 21 million would become extremely scarce, and the constant that bitcoin provides would offer even greater utility in facilitating trade.

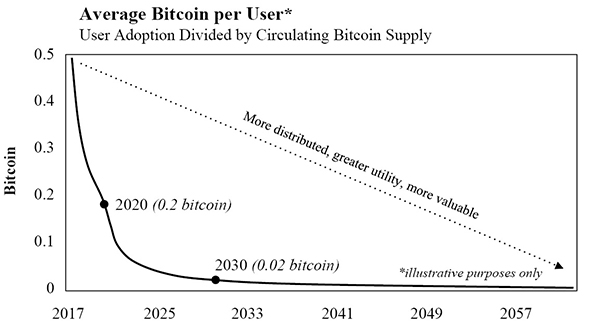

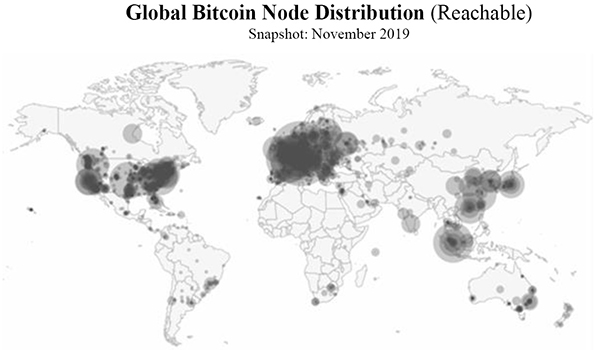

Increased demand combined with a fixed supply naturally results in bitcoin becoming more distributed. There is only so much to go around, and the pie ends up getting split up into smaller and smaller shares owned by more and more people. As more individuals value bitcoin, the network not only becomes a greater utility, but it also becomes more secure. It becomes a greater utility because more people are communicating in the same language of value and trading through a more reliable constant. And as more individuals participate in the network consensus mechanism, the entire system becomes more resistant to corruption and ultimately more secure. Recognize that there is nothing about a software application or a “blockchain” that guarantees a fixed supply, and bitcoin’s supply schedule is not credible because software dictates it. Instead, 21 million is only credible because it is governed on a decentralized basis and by an ever-increasing number of network participants. The more decentralized bitcoin becomes, the more secure it is. As more individuals participate in consensus, 21 million becomes a more credibly fixed number. Similarly, bitcoin becomes a more reliable constant as each individual controls a smaller and smaller share over time. As adoption increases, security and utility work in lockstep. Consider the distribution and relative density of bitcoin adoption worldwide. As reach and density within each market spread, bitcoin’s constant hardens and becomes harder to change.

Source: Bitnodes.io

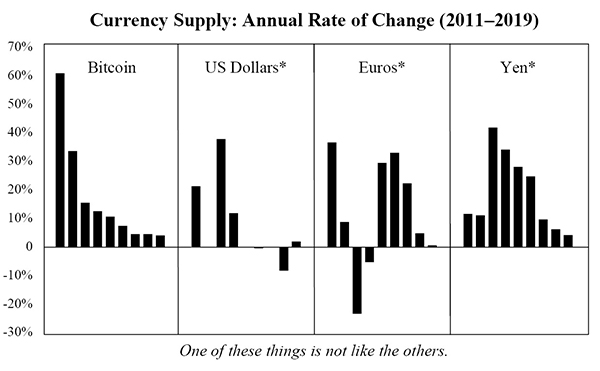

As individuals increasingly opt in, bitcoin’s terminal supply of 21 million becomes more and more credible. In the mind of those who adopt it, finite scarcity becomes what differentiates bitcoin from all other forms of money—both legacy currencies and competing cryptocurrencies alike. All other currencies either become centralized over time (e.g., the dollar, euro, yen, gold) or were too centralized from the start (e.g., all other cryptocurrencies) to credibly compete with a fixed supply of 21 million. Centralization inherently creates the need to rely on trust, and trust puts the supply of any currency at risk. As history has shown, the desire and impulse to print money are far too great to resist, and an inflating currency supply ultimately impairs demand and marginalizes utility of the currency in the function of exchange. Whereas all other currencies depend on trust, bitcoin provides a trustless constant. Twenty-one million is only credible because bitcoin is decentralized, and bitcoin becomes increasingly decentralized over time. The best any other form of money could possibly do is match bitcoin. However, even that is not possible because individuals converge on a single form of money, and bitcoin has already beaten every other currency to the punch. Every other currency is ultimately competing against the ideal constant—one that is fixed, will not change, and does not rely on trust.

Source: Federal Reserve Economic Data (FRED)

All forms of money compete with each other for every exchange. If an asset’s primary (or sole) utility is the exchange for other goods and services, and if it does not have a claim on the income stream of a productive asset such as a stock or bond, it must compete as a form of money. As a consequence, any such asset is directly competing with bitcoin for the exact same use case. And because bitcoin already exists and is finite, no other currency will ever provide a more reliable constant. Scarcity in bitcoin will also be perpetually reinforced on both the supply and demand side for the reason that individuals converge on a single form of money. At the same time, the opposite force will be in effect for all other currencies due to the reflexive nature of monetary competition. The distinction between two monetary goods is never marginal, and neither is the consequence of individual decisions to exchange in one medium rather than another. Money is an intersubjective problem, and opting in to one monetary medium explicitly means opting out of another, even if on a marginal basis with each trade or exchange. One currency gains value and utility at the direct expense of the other. As bitcoin becomes more scarce and more reliable as a constant, other currencies become less scarce and more variable (i.e., less stable and more volatile). Monetary competition is zero-sum, and relative scarcity, a dynamic function of supply and demand, creates the fundamental differentiation between two monetary mediums, which only increases and becomes more apparent over time.

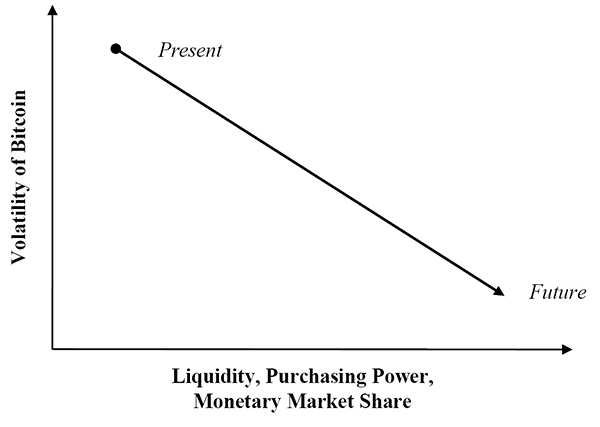

But remember, scarcity for scarcity’s sake is not the goal of any money. Instead, the money that provides the greatest constant will facilitate exchange most effectively. The monetary good with the greatest relative scarcity will best preserve value between present and future exchanges over time. The relative price and relative value of all other goods is the information desired from the coordination function of money, and in every exchange, each individual is incentivized to maximize present value into the future. Finite scarcity in bitcoin provides the greatest assurance that value exchanged in the present will be preserved into the future. As more and more individuals collectively identify that bitcoin is the monetary good with the greatest relative scarcity, stability in its price will become an emergent property.

The Greatest Measurement Tool—Divisibility

While scarcity is the bedrock of a monetary good, not all scarce goods are functional as money. To effectively communicate value, a monetary good must be a relative constant, easy to measure, and functional in exchange—all three in aggregate. Naturally, goods that are easy to measure or otherwise serve as measurement tools are not necessarily effective in the exchange of value. A ruler may be an effective measurement tool, but rulers are not scarce, nor can they be easily divided or aggregated into larger and smaller units to facilitate exchange. A monetary good being scarce and measurable allows for the measurement of all other goods. However, the ability to easily subdivide and transfer a monetary unit provides practical utility in exchange, without which a particular good would not be used as a standard to measure value. Bitcoin combines finite scarcity with the ability to subdivide each whole unit down to eight decimal points (0.00000001 or one 100,000,000th of a bitcoin) and transfer any amount of value, however large or small. Just as scarcity for scarcity’s sake is not necessarily valuable in the context of money, neither is the property of divisibility. It is the combination that becomes valuable in the context of money, particularly when each subdivided unit is fungible (i.e., essentially interchangeable, with each part indistinguishable from another). These properties jointly allow bitcoin to be both a perfect constant and an effective measure of value to facilitate exchange.

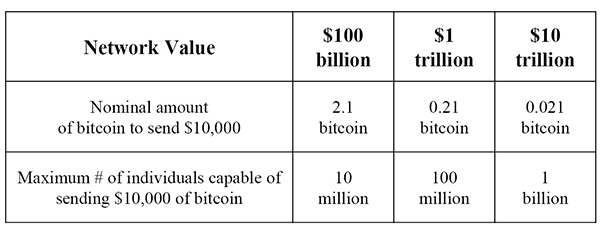

In the code, one bitcoin is represented as 100,000,000 sub-units, with the smallest unit referred to as a satoshi (or sat for short). Technically, one bitcoin is 100,000,000 sats. While one bitcoin equates to approximately $9,000 as of the time of writing, one satoshi equals one-twentieth of a penny. In essence, anyone can exchange any amount of value for bitcoin. Bitcoin, as with any money, is functional for one purpose, to store value between a series of exchanges. Receive bitcoin for value produced today, save, and spend bitcoin in the future in exchange for value produced by others. Bitcoin will perform the same function regardless of the amount. The practical consequence of divisibility is that bitcoin can measure any and all value, allowing it to support any and all adoption. Individuals produce a wide range of value, and divisibility allows all individuals to utilize bitcoin as a savings mechanism, whether it be to store $50 or $50,000 worth of value. For a monetary good to be an effective exchange tool, it must be able to measure the range of value produced by all individuals—something bitcoin does flawlessly. The ability to divide and transfer any amount of bitcoin makes it accessible to all individuals and, ultimately, all goods produced, regardless of how much value is attributable to each.

In the A/B test of monetary competition, if A>B, any amount of A will perform the function of money better than any amount of B. Over time, A will increase in purchasing power relative to B, whether for $50 or $50,000 worth of value. Never be confused by a list of cryptocurrencies trading on Coinbase that look like a better deal because the price is “cheap” whereas bitcoin appears “expensive.” Remember that bitcoin can be divided into smaller or larger units to store more or less value. One bitcoin is an inherently arbitrary unit, as is one unit of any currency. The market test is whether A is more functional as money than B. It is an intersubjective decision, and while the market is communicating which network it believes performs the monetary function more effectively through price and value, network value is the output—not the input. The input is each individual evaluating the properties of the monetary good itself relative to others. If bitcoin is A in your evaluation, then there is no “too expensive.” Bitcoin may be overvalued or undervalued at any point in time, but each individual that adopts bitcoin increases the value of the network (recall the discussion on trading partners and network connections). And the ability to be divided easily into very small units allows a practically limitless number of individuals to convert and communicate value through the network. If A is greater than B, and if A can support unlimited adoption, it eventually obsoletes the need for network B entirely.

As individuals independently evaluate this A/B test, more people ultimately adopt bitcoin, and bitcoin becomes divided into smaller and smaller units (on average). This is the result of increasing demand combined with a fixed supply, and the value of the network actually increases as a function of this process. As a network, bitcoin becomes more valuable as it is valued by more people. Essentially, 0.1 bitcoin = $1,000 is more valuable than 1.0 bitcoin = $1,000, despite each being worth the same measured in dollar terms. More exchange becomes possible as bitcoin becomes more valuable, with value being the output of more and more people choosing to adopt bitcoin as an exchange intermediary. Each individual owns a smaller and smaller nominal amount of currency, but each equivalent unit’s purchasing power increases over time. With each exchange, every individual is conveying their own value onto the network and is doing so at the direct expense of a competing monetary network. This process determines a new price specific to the value created and measured by each individual. As a result, bitcoin accumulates more information derived from a more diverse set of trading partners.

While prices today may not yet be quoted in bitcoin terms, a pricing system is forming every time an individual converts value into bitcoin. Even if dollars are an indirect intermediary, value produced somewhere in the world, distinct to a particular individual, is expressed as a unit of bitcoin. As more and more people choose to do so and increasingly on a per-individual basis, that value converts to a smaller and smaller unit of bitcoin (on average). The consequence is that more people can use a smaller and smaller denomination of bitcoin to transfer an equivalent amount of value, and as bitcoin is measured by more people—and more goods are priced or valued in bitcoin terms—its ability to measure relative value only increases. Since bitcoin can measure all value and can support adoption by a limitless number of individuals, it practically obsoletes the need for any other value-transfer network over the long term. Finite scarcity combined with divisibility creates an extremely powerful exchange intermediary. Bitcoin has the lowest terminal rate of change possible due to its absolute scarcity, and it can be divided into a fraction of a penny—which combined, will allow it to measure value far more precisely than any other currency.

The Greatest Exchange Tool—Transferability

With this baseline, the real knockout punch is the fact that bitcoin can be transferred, on an irrevocable basis, over a communication channel without needing a trusted third party as an intermediary. This is fundamentally different from digital payments in fiat systems, which depend entirely on trusted intermediaries. In aggregate, bitcoin is a greater constant than any other form of money, is highly divisible and measurable, and is capable of being transferred over the internet with reliable final settlement. Try to identify a single other good that could possibly share these properties: finite scarcity (greatest constant) + divisibility and fungibility (measurement) + the ability to send over a communication channel (ease of transfer). This is what every other monetary good is up against as it competes for the convergent role of money. The only way to truly appreciate the power of such a rare dynamic is by experiencing it firsthand. Any individual can access the network on a permissionless basis by running a bitcoin node on a home computer. The ability to power up a computer anywhere in the world and transfer a finitely scarce resource to any other individual without permission or reliance on a trusted third party is empowering. That hundreds of millions of people can do this in unison without anyone needing to trust other participants in the network is near-impossible to fully comprehend.

Bitcoin is often described as digital gold, but this does not do it justice. Bitcoin combines the strengths of physical gold and the strengths of the digital dollar without the limitations of either. Gold is scarce but difficult to divide and transfer. The dollar is easy to transfer but lacks scarcity. Bitcoin is finitely scarce, easy to divide, and easy to transfer. In their current forms, gold as well as all fiat monetary systems depend on trust, whereas bitcoin is trustless. Bitcoin has optimized for the strengths and weaknesses of both, which is fundamentally why the market is converging (and will continue to converge) on bitcoin to fulfill the function of money.

Bitcoin Obsoletes All Other Money

If any individual comes to the following three conclusions, that individual is going to more consciously seek out the best form of money.

- Money is a basic necessity.

- Money is not a collective hallucination.

- Economic systems converge on a single form of money.

Money is the economic good that preserves value into the future and allows individuals to convert their own time and skills into a range of choice so great that prior generations would find it difficult to imagine. Freedom is ultimately what a reliable form of money provides: freedom to pursue individual interests (specialization) and convert the output of that value into the value created by others (trade). Whether individuals consciously ask themselves these questions or not, they will be forced to answer them through their actions. Even those who do not will also arrive at the same answer as those who do. The conscious and the subconscious arrive at the same place because the fundamental truths do not change, and the function of money is singular: to intermediate a series of present and future exchanges by providing the baseline to communicate subjective value among a broad group of individuals who stand to benefit from trade and specialization. Money is a basic necessity. It is not a collective hallucination. And there are discernible properties that make certain goods more or less functional in exchange, which is an inherently intersubjective problem.

Owning bitcoin is becoming the cost of entry to what will likely be the largest and most diverse economy ever to exist. Bitcoin is global, and it is accessible on a permissionless basis. Because bitcoin becomes the common language of value for all participants, anyone that is a part of the network will be able to communicate and ultimately trade with other network participants. The more trading partners there are in the network, the greater the value each unit provides to currency holders. While there will likely always be jurisdictional friction that impedes trade, access to the same common currency removes the root source of friction in the communication and exchange of value, and bitcoin’s fixed supply will allow its pricing mechanism to accumulate and communicate information with the least distortion relative to any other form of money. And as more individuals choose to store value in bitcoin, its fixed supply becomes more credible and its pricing mechanism more reliable and relevant. New adopters of a monetary network contribute value and realize value as a function of adoption, which is why it is not possible to be late to bitcoin, nor will bitcoin ever be too expensive.

At the end of the day, it does not matter how complicated bitcoin may seem. The decision to adopt bitcoin becomes an A/B test. The need for money is real, and individuals will converge on the form of money that best fulfills the function of exchange. No other currency in the world can ever be more scarce than bitcoin, and scarcity will act as a gravitational force, driving adoption and the communication of value. Today, most billionaires do not understand bitcoin. Bitcoin is an equal opportunity mind-bender. But even those who do not understand bitcoin will come to rely upon it. There are many fundamental questions. Bitcoin is volatile, seemingly slow, faces challenges to scaling, is not commonly used for payments, consumes a lot of energy, etc. Stability is an emergent property that will follow from broader adoption, and all other perceived limitations will be solved as a function of the value that is derived from finite scarcity combined with the ability to measure, divide, and transfer value. That is the innovation of bitcoin. Currency A has a fixed supply, while Currency B does not. Currency A continues to increase in value relative to Currency B. Currency A also continues to increase in purchasing power relative to goods and services, while Currency B does the opposite. Which one do I want? A or B? Choose wisely because the opportunity cost is your time and value. In practice, it all comes down to common sense and survival instincts. Bitcoin obsoletes all other money because economic systems converge on a single currency, and bitcoin has the most credible monetary properties.