Chapter Three

Bitcoin Is Not Backed by Nothing

Originally published

on 27 September 2019

Popular Misbelief

The critics often clamor like a broken record that “bitcoin isn’t backed by anything.” However, contrary to popular belief, bitcoin is backed by something. In fact, it is backed by the only thing that has ever backed any form of money: the credibility of its monetary properties. Money is not a collective hallucination, nor is it merely a belief system—two common myths. Over the course of history, various goods have emerged as money, and each time, it has not been by coincidence. Instead, these goods possessed properties that made them particularly useful and differentiated as a means of exchange—typically a combination of scarcity, durability, divisibility, fungibility, and portability, among others. With each emergent form of money, inherent properties of one medium improve upon and obsolete the monetary properties of a pre-existing form of money. Every time that one good has emerged as money, another was consequently demonetized. Essentially, the relative strengths of one monetary medium outcompete that of another. Bitcoin is no different. It represents a technological advancement in the global competition for money. Bitcoin is the superior successor to gold and the fiat money systems that leveraged gold’s monetary properties.

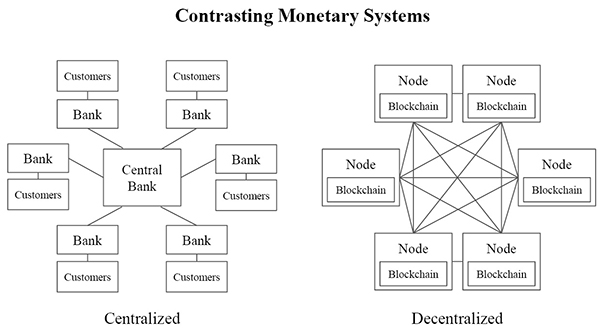

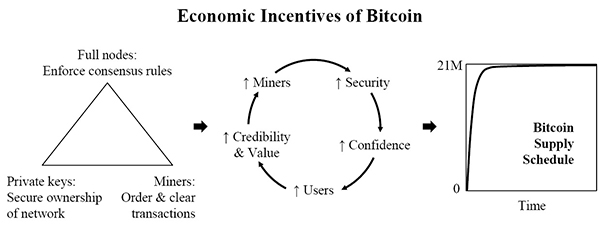

Bitcoin is finitely scarce, and it is easier to transfer than its incumbent competitors. It is also decentralized, and more resistant to censorship or corruption as a result. There will only ever be 21 million bitcoin, and each bitcoin is divisible to eight decimal points (1 one-hundred millionth). Value can be transferred to anyone and to anywhere in the world on a permissionless basis without reliance on any third-party for final settlement. In aggregate, bitcoin is outcompeting its analog predecessors based on the credibility of its monetary properties, which are vastly superior to any other form of money used today. However, the key word is credibility. The emergent monetary properties in bitcoin are secured and reinforced through a combination of cryptography, a network of decentralized nodes enforcing a common set of consensus rules, and a robust mining network ensuring the integrity and immutability of bitcoin’s transaction ledger. The currency itself is the keystone that binds the system together, creating economic incentives that allow the security columns to function as a whole. But even still, bitcoin’s monetary properties are neither absolute nor considered in a vacuum. Instead, the strength and credibility of these properties are evaluated by the market relative to the properties inherent in other monetary systems.

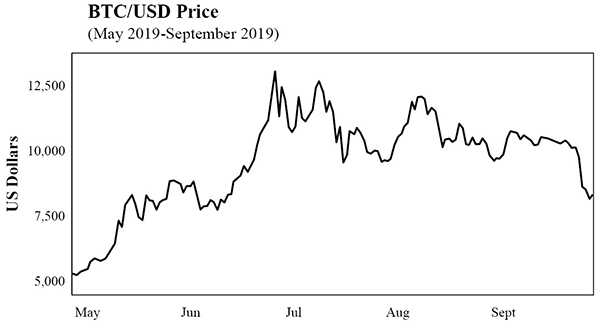

Source: Bitstamp

Recognize that every time a dollar is sold for bitcoin, the exact same number of dollars and bitcoin exist in the world. Exchanges between bitcoin and dollars have no impact, at all, on the supply of either currency. Nothing changes except the market’s preference to hold one currency versus the other. As the value of bitcoin rises, it is an indication that market participants increasingly prefer holding bitcoin over dollars. A higher price of bitcoin (in dollar terms) means more dollars must be sold to acquire an equivalent amount of bitcoin. In aggregate, it is an evaluation by the market of the relative strength of monetary properties. Price is the output. Monetary properties are the input. As individuals evaluate the monetary properties of bitcoin, the natural question becomes: which currency possesses more credible monetary properties? Bitcoin or the dollar? Well, what backs the dollar (or euro or yen, etc.) in the first place? When attempting to answer this question, the common refrain is that the dollar is backed by the government, the military (guys with guns), or taxes. However, the dollar is backed by none of these. Not the government, not the military, and not taxes. Governments tax what is valuable. A good is not valuable because it is taxed. Similarly, militaries secure what is valuable, not the other way around. Ultimately, a government cannot dictate the value of its currency. It can only control its supply and who has access.

Venezuela, Argentina, and Turkey all have governments, militaries, and the authority to tax, yet the currencies of each have deteriorated significantly over the past five years. While it’s not sufficient to prove the counterfactual, each is an example that contradicts the idea that a currency derives its value as a function of government. Each and every occurrence of hyperinflation should be evidence enough of the inherent flaws in fiat monetary systems, but unfortunately it is not. Rather than acknowledging hyperinflation as the logical end game of all fiat systems, most simply believe hyperinflation to be evidence of monetary mismanagement. This simplistic view ignores first principles, as well as the dynamics that ensure monetary debasement in fiat systems. While the dollar is structurally more resilient as the global reserve currency, the underpinning of all fiat money is functionally the same, and the dollar is merely the strongest of a weak lot. As with all currencies, bitcoin is competing with the dollar based on the relative strengths of its monetary properties. A baseline understanding of one is necessary to then compare and evaluate the other. After all, the competition is relative.

Why Does the Dollar Have Value?

The value of the dollar did not emerge on the free market. Instead, it emerged as a fractional representation of gold (and silver, initially). Essentially, the dollar was a solution to the limitations that existed in the convertibility and transferability of gold, having no inherent monetary properties of its own. From the onset, the dollar as a currency system was always based on trust: deposit gold at a bank, accept dollars in return, and trust that dollars could be converted back to gold at a fixed amount in the future. Gold’s limitation and ultimate failure as money is the dollar system, and without gold, the dollar would have never existed in its current construct. Here is a quick review of the dollar’s history with gold:

| 1900 | The Gold Standard Act established gold as the only metal convertible to dollars at $20.67 per oz. |

| 1913 | The Federal Reserve was created as part of the Federal Reserve Act. |

| 1933 | President Roosevelt banned gold hoarding via Executive Order 6102, requiring conversion to dollars at $20.67 per oz. or face penalties. |

| 1934 | The Gold Reserve Act devalued the dollar by ~40% to $35 per oz. of gold. |

| 1944 | The Bretton Woods Agreement formalized gold-dollar convertibility at $35 per oz. and established fixed exchange ratios with other currencies. |

| 1971 | President Nixon ended dollar-gold convertibility, ending Bretton Woods. Dollar value changed to $38 per oz. of gold. |

| 1973 | US government repriced gold to $42 per oz. |

| 1976 | US government decoupled the dollar's value from gold entirely. |

Over the course of the twentieth century, the dollar transitioned from a reserve-backed currency to a debt-backed currency. While most people never stop to consider why the dollar has value in the post-gold era, the most common explanation remains that it is either a collective hallucination (i.e., the dollar has value simply because we all believe it does) or that it is a function of the government, the military, and taxes. Neither explanation has any basis in logic, nor is it the fundamental reason why the dollar retains value. Hundreds of millions of Americans are not all collectively hallucinating, and the dollar does not have value because of the military or the government’s ability to tax. Instead, today, the dollar maintains its value as a function of debt and the relative scarcity of dollars to dollar-denominated debt. In the dollar world, everything is a function of the credit system. The mechanisms that fund the government (taxes and deficit spending) are both dependent on the credit system, and the credit system is what allows the dollar to function in its current construct.

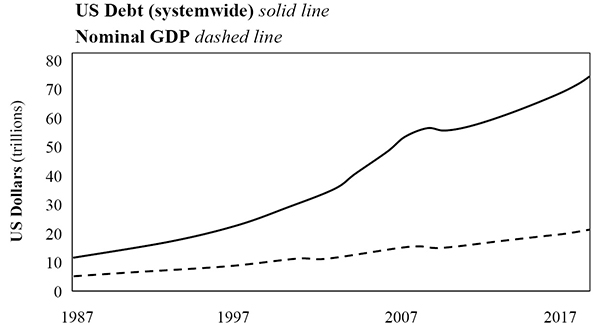

Source: Federal Reserve Economic Data (FRED)

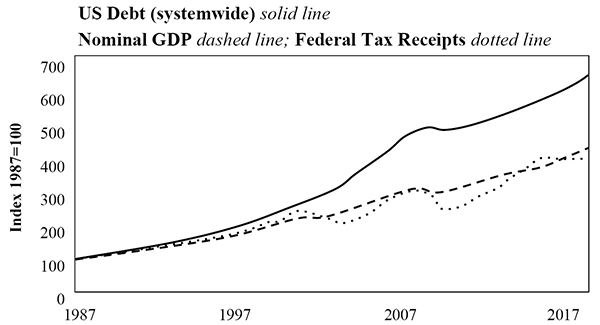

The size of the credit system is several times larger than US nominal GDP, and it is orders of magnitude larger than the base money supply. Because of the credit system’s relative size, economic activity in the US is largely coordinated through the allocation and expansion of credit. The chart below indexes the rate of change of the credit system compared to the rate of change of both nominal GDP and federal tax receipts (from 1987 to today). In the Fed’s system, credit expansion drives nominal GDP, which ultimately dictates the nominal level of federal tax receipts.

Source: Federal Reserve Economic Data (FRED)

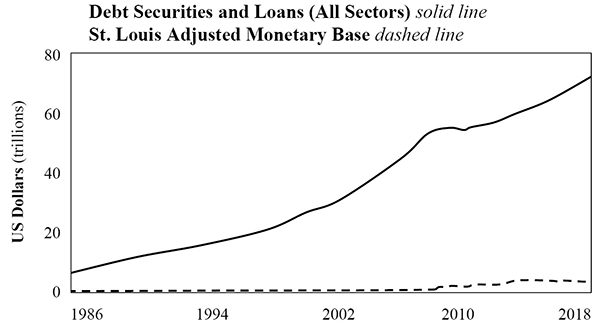

As of the time of writing, there is $73 trillion of dollar-denominated debt (fixed maturity / fixed liability) in the US credit system,[5] but there are only $1.6 trillion actual dollars in the banking system.[6] Dollar debt creates future demand for dollars, and in the Fed’s system, each dollar is leveraged approximately 40:1. If you borrow dollars today, you will need to source dollars in the future to repay that debt, and currently, each dollar in the banking system is owed 40 times over. The relationship between the size of the credit system relative to the amount of dollars creates scarcity in the dollar. In aggregate, everyone needs dollars to repay dollar-denominated credit.

Source: Federal Reserve Economic Data (FRED)

The system as a whole owes far more dollars in debt than actually exist in circulation, creating an environment in which there is always a very high present demand for dollars. If consumers did not repay debt, homes would face foreclosure, and cars could be repossessed. If a corporation did not repay debt, company assets would be forfeited to creditors via a bankruptcy process, and equity could be entirely wiped out. If a government did not repay debt, basic government functions would be shut down due to lack of funding. In most cases, the consequence of not securing the future dollars necessary to repay debt means losing the shirt on your back. Debt creates the ultimate incentive to demand dollars. So long as dollars are scarce relative to the amount of outstanding debt, the dollar remains relatively stable and in very high demand. The Fed incentivizes credit creation by artificially reducing the cost of credit, which then creates the source of future demand for the underlying currency—like a drug dealer getting addicts hooked on drugs, creating future dependency. In this case, the drug is debt, and it forces everyone, on average, to stay on the dollar hamster wheel.

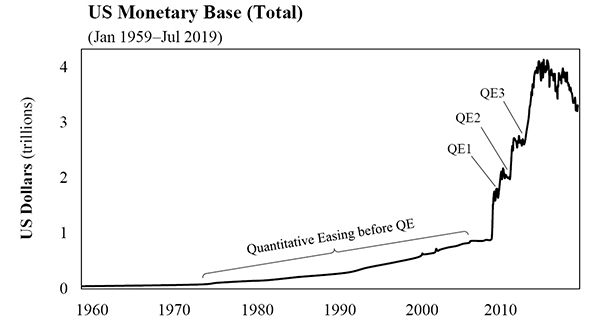

The problem for the Fed’s economy (and the dollar) is that it depends on the functioning of a highly leveraged credit system. And in order to sustain the amount of debt in the system, the Fed has to systematically increase the supply of actual dollars. Otherwise, the credit system would collapse. This is what quantitative easing is and why it exists (see Bitcoin Fixes This). Increasing the amount of base dollars has the immediate effect of deleveraging the credit system, but it has the longer-term effect of inducing more credit expansion. It also has the effect of devaluing the dollar gradually over time. This is all by design. Credit is ultimately what backs the dollar because what the credit actually represents is claims on real assets and, consequently, people’s livelihoods. “Come with dollars in the future, or risk losing your house” is an incredible incentive to work for dollars.

The relationship between dollars and dollar credit keeps the Fed’s game in play, and central bankers believe this can go on forever. Too much debt? Create more dollars. With more dollars, create more debt until there is too much, and so on. Ultimately, in the Fed’s system (or any central bank’s), the currency is the release valve. Because there is $73 trillion of debt and only $1.6 trillion actual dollars in the US banking system, more dollars will have to be added to the system to support the debt. The scarcity of dollars relative to the demand for dollars is what gives the dollar its value. Nothing more, nothing less. Nothing else backs the dollar. And while the dynamics of the credit system create relative scarcity of the dollar, it is also what ensures dollars will become less and less scarce on an absolute basis.

Too Much Debt → Create More Money → More Debt → Too Much Debt

Source: Federal Reserve Economic Data (FRED)

As with any form of money, scarcity is the principal property that backs the dollar. But the dollar is only scarce relative to the amount of dollar-denominated debt that exists. And it now has real competition in the form of bitcoin. The dollar system and its lack of inherent monetary properties provides a stark contrast to the monetary properties emergent and inherent in bitcoin. Dollar scarcity is relative. Bitcoin scarcity is absolute. The dollar system is based on trust. Bitcoin is not. The dollar’s supply is governed by a central bank, whereas bitcoin’s supply is governed by a consensus of market participants. The supply of dollars will always be wed to the size of its credit system, whereas the supply of bitcoin is entirely divorced from the function of credit. And the marginal cost to create dollars is zero, whereas the cost to create bitcoin is tangible and ever-increasing. Ultimately, bitcoin’s monetary properties are emergent and increasingly unmanipulable, whereas the dollar is inherently and increasingly manipulable. And everything true of the dollar is true of any central bank’s currency.

Money and Digital Scarcity

When evaluating bitcoin as money, the hardest mental hurdle to overcome is often its digital nature. Bitcoin is not tangible, and on the surface, it is not intuitive. How could something that is entirely digital be money? The dollar is mostly digital, yet it remains far more tangible than bitcoin in the minds of most. While the digital dollar emerged from its paper predecessor and physical dollars remain in circulation, bitcoin is natively digital. With the dollar, there is a physical bill that anchors your mental model in the tangible world. With bitcoin, there is not. Bitcoin possesses far more credible monetary properties than the dollar, but the dollar has always been money. While the dollar may be anchored in time and the physical world, the supply of dollars has no limits. Bitcoin, on the other hand, is finitely scarce.

Remember that the dollar does not have any inherent monetary properties. No unique properties ground the dollar as a stable form of money, other than its relative scarcity to the amount of dollar-denominated debt. Instead, the dollar leveraged the monetary properties of gold in its ascent to global reserve status. As a result, when evaluating bitcoin, the principles-based question to consider is whether bitcoin shares the quintessential properties that caused gold to emerge as money. Did gold emerge as money because it was physical or because it possessed transcendent properties beyond being physical? Of all the physical objects in the world, why gold? Gold emerged as money not because it was physical but instead because its aggregate set of properties was unique and particularly well suited for storing and exchanging value. Most importantly, gold is scarce, fungible, and highly durable. While gold possessed many properties that made it superior to any money that came before it, its fatal flaw was that it was difficult to transport and susceptible to centralization, which is ultimately why the dollar emerged as its transactional counterpart.

As a thought experiment, imagine there was a base metal as scarce as gold but with the following properties:

- boring grey in colour

- not a good conductor of electricity

- not particularly strong, but not ductile or easily malleable either

- not useful for any practical or ornamental purpose

and one special, magical property:

- can be transported over a communications channel

Bitcoin shares the monetary properties that caused gold to emerge as a monetary medium, but it also improves upon gold’s flaws. While gold is relatively scarce, bitcoin is finitely scarce, and both are extremely durable. While gold is fungible, it is difficult to assay. Bitcoin is fungible and easy to assay. Gold is difficult to transfer and highly centralized. Bitcoin is easy to transfer and highly decentralized. Essentially, bitcoin possesses all the desirable traits of both physical gold and the digital dollar combined in one, but without the critical flaws of either. When evaluating monetary mediums, first principles are fundamental anchor points. Ignore the conclusion or end point, and start by asking yourself: if bitcoin were actually scarce and finite, ignoring that it is digital, could that be an effective measure of value and ultimately a store of value? Is scarcity a sufficiently powerful property to allow bitcoin to emerge as money, regardless of whether the form of that scarcity is digital?

As a tool, money is used to measure and exchange value. It is the good that coordinates all other economic activity, and scarcity is money’s most important and foundational property. Scarcity relative to more abundant consumption goods and capital goods is what allows money to collectively store, measure, and exchange value. The absolute quantity of money is less important than its properties of being scarce, measurable, and capable of being transferred in exchange for goods and services. Despite being digital, bitcoin is designed to provide absolute scarcity, which is why it has the potential to be such an effective form of money (and measure of value). There will only ever be 21 million bitcoin. It provides a medium with finite scarcity that can be easily transferred. Dollars may seem easy to transfer, but the Fed created $100 billion new dollars just last week, with the click of a button. That is approximately $5,000 for every bitcoin that will ever exist, created in just a week (and by only one central bank). Since the Great Financial Crisis, the Federal Reserve, the Bank of Japan, and the European Central Bank have collectively created $10 trillion worth of new money, the equivalent of approximately $500,000 per bitcoin. Despite dollars, euros, yen, and bitcoin all being digital, bitcoin is the only medium that is tangibly scarce and the only one with inherent monetary properties.

However, it is insufficient to simply claim that bitcoin is finitely scarce. Nor should anyone accept this as fact. It is important to understand how and why that is the case. Credibility is the key. How does bitcoin credibly enforce its fixed supply? Why can’t more than 21 million bitcoin be created? Why can’t bitcoin be copied? While there are many pieces to the puzzle, three key architectural elements allow bitcoin to function with a reliably fixed supply when woven together with the economic incentives of the currency itself:

- Network consensus and full nodes: enforce a common set of governing rules

- Mining and proof-of-work: validate transaction history and anchor bitcoin security in the physical world

- Private keys: secure the unit of value and ensure ownership is independent from validation

What Secures Bitcoin—Network Consensus and Full Nodes

Twenty-one million is not just a number guaranteed by software. Instead, bitcoin’s fixed 21 million supply is governed by a consensus mechanism, and all market participants have an economic incentive to enforce the rules of the bitcoin network. While a consensus of the bitcoin network could theoretically determine to increase the supply of bitcoin such that it exceeds 21 million, an overwhelming majority of bitcoin users would have to collectively agree to debase their own currency to do so. In practice, a global and decentralized network of rational economic actors, operating within a voluntary, opt-in currency system, would not collectively and overwhelmingly form a consensus to debase the currency that they have all independently and voluntarily determined to use as a store of wealth. This economic incentive underpins and reinforces bitcoin’s technical architecture and network effect.

In bitcoin, a full node is a computer or server that maintains a full version of the bitcoin blockchain. Full nodes independently aggregate a version of the blockchain based on a common set of network consensus rules. While not everyone that holds bitcoin runs a full node, everyone is able to do so, and each node validates all bitcoin transactions and all blocks. By running a full node, anyone can access the bitcoin network and broadcast transactions (or blocks) on a permissionless basis. And nodes do not trust any other nodes. Instead, each node independently verifies the complete history of bitcoin transactions based on a common set of rules, allowing the network to converge on a consistent and accurate version of history on a trustless basis—that is consensus.

The bitcoin network removes trust in any centralized third party through this mechanism, which hardens the credibility of its fixed supply. All nodes maintain a history of all transactions, allowing each node to determine whether any future transaction is valid. In aggregate, bitcoin represents the most secure computing network in the world because anyone can access it, and no one trusts anyone. The network is decentralized, and there are no single points of failure. Each node is also a redundancy to every other node, from a record-keeping and validation perspective. Every node represents a check and balance on the rest of the network, and without a central source of truth, the network is resistant to attack and corruption. Any node could fail or could become corrupted, and the rest of the network would remain unimpacted. The more nodes that exist, the more decentralized bitcoin becomes, which increases redundancy and makes the network harder and harder to corrupt or censor.

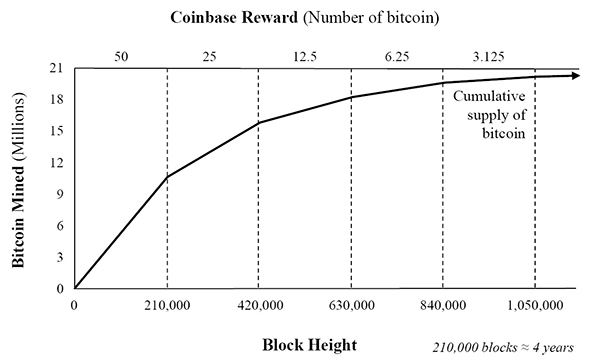

Each full node enforces the consensus rules of the network, a critical element of which is the currency’s fixed supply. Each bitcoin block includes a predefined number of bitcoin to be issued, and each bitcoin transaction must have originated from a previously valid block in order to be valid. Every 210,000 blocks, the bitcoin issued in each valid block is cut in half until the amount of bitcoin issued ultimately reaches zero in approximately 2140, creating an asymptotic, capped supply schedule. Because each node independently validates every transaction and each block, the network collectively enforces the fixed 21 million supply. If any node were to broadcast an invalid transaction or block, the rest of the network would reject it and that node would fall out of consensus. Essentially, any node could attempt to create excess bitcoin, but every other node has an interest in ensuring the supply of bitcoin is consistent with the predefined fixed limit. Otherwise, the currency would be arbitrarily debased at the direct expense of the rest of the network. No one has an incentive to allow others to arbitrarily create money, and everyone has the incentive to prevent it from happening.

Separately, anyone within or outside the network could copy bitcoin’s software to create a different version of bitcoin. But any currency units created by such a copy would be considered invalid by the nodes operating within the bitcoin network because the units would not have originated from a previously valid bitcoin block. Nor would anyone accept the currency as bitcoin. Each bitcoin node independently validates whether a bitcoin is a bitcoin. It would be like trying to pass off Monopoly money as dollars. No one would accept it as bitcoin, nor would it share the emergent properties or infrastructure of the bitcoin network. Running a bitcoin full node allows anyone to instantly assay whether a bitcoin is valid, and any copy of bitcoin would be immediately identified as counterfeit and invalid. The consensus of nodes determines the valid state of the network within a closed-loop system. When anything occurs outside its walls—anything inconsistent with its consensus rules—it’s as if it never happened.

What Secures Bitcoin—Mining and Proof-of-Work

As part of the consensus mechanism, certain nodes (referred to as miners) also perform bitcoin’s proof-of-work function to add new bitcoin blocks to the blockchain. This function validates the complete history of transactions and clears pending transactions. The process of mining is ultimately what anchors bitcoin security in the physical world. To solve blocks, miners must perform trillions of cryptographic computations, which requires expending significant energy resources. Once a block is solved, it is proposed to the rest of the network for validation. All nodes (including other miners) verify whether a block is valid based on the common set of network consensus rules discussed previously. If any transaction in the block is invalid, the entire block is invalid. Separately, if a proposed block does not build on the latest valid block (i.e., the longest version of the block chain), the block is also invalid.

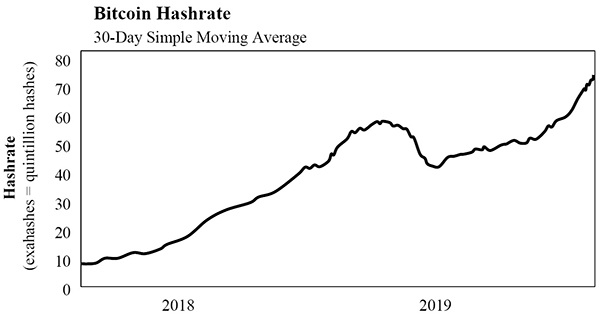

For context, at 90 exahashes per second, approximately 9 gigawatts of power distributed throughout the world currently secures the bitcoin network, which equates to ~$11 million per day (~$4 billion per year) of energy at a marginal cost of 5 cents per kWh (rough estimates). Blocks are solved on average every ten minutes, which translates to approximately 144 blocks per day. Across the network, each block currently requires approximately $75,000 in energy expenditure to solve, and the reward per block is approximately $100,000 (12.5 new bitcoin x $8,000 per bitcoin as of the time of writing, excluding transaction fees). The higher the cost to solve a block, the more costly the network is to attack. The cost to solve a block represents the tangible resources it requires to write history to the bitcoin transaction ledger, which functionally clears transactions for final settlement. As the network grows, the network becomes more fragmented, and the economic value compensated to miners in aggregate increases. From a game-theory perspective, more competition and greater opportunity cost make it harder to collude, and all network nodes validate the work performed by miners, which serves as a check and balance.

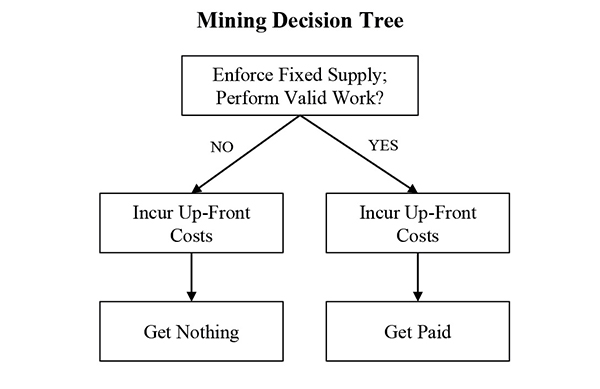

Source: bitinfocharts.com

Recall that a predefined number of bitcoin are issued in each valid block (that is, until the 21 million limit is reached). The bitcoin issued in each block combined with network transaction fees represent the compensation to miners for performing the proof-of-work function. Importantly, the miners are paid exclusively in bitcoin to secure the network. As part of the block construction and proposal process, miners include the predefined number of bitcoin—consistent with the fixed supply schedule—to be issued as compensation for expending tangible, real-world resources to secure the network. If a miner were to include an amount of bitcoin greater than the predefined supply schedule as compensation, the rest of the network would reject the block as invalid. As part of the security function, miners must validate and enforce the fixed supply of the currency in order to be compensated. Miners have material skin in the game in the form of up-front capital costs (and energy expenditure), and invalid work is not rewarded or compensated.

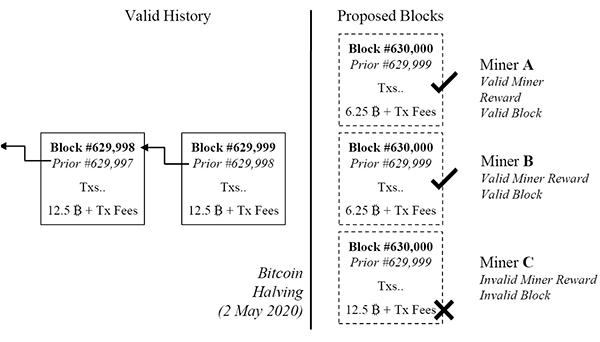

For a technical example, the valid reward paid to miners is halved every 210,000 blocks with the next halving of issuance scheduled to occur at block 630,000 (or approximately in May 2020). At that time and scheduled block, the valid reward will be reduced from 12.5 bitcoin to 6.25 bitcoin per block. Thereafter, if any miner includes an invalid reward (an amount greater than 6.25 bitcoin), the rest of the network will reject it as invalid. The halving event is important not just because the supply of newly issued bitcoin is reduced, but also because it demonstrates that the economic incentives of the network continue to effectively coordinate and enforce the fixed supply of the currency on an entirely decentralized basis. If any miner ever attempts to cheat, it will be maximally penalized by the rest of the network. Nothing other than the economic incentives of the network coordinate this behavior. That it occurs on a decentralized basis without the coordination of any central authority reinforces the security of the network.

Because mining is decentralized and because all miners are constantly competing with all other miners, it is not practical for miners to collude. Separately, all nodes validate the work performed by miners, instantly and at practically no cost, which creates a very powerful check and balance that is divorced from the mining function itself. Miners are not the only constituents validating the work of other miners. Blocks are costly to solve but easy to validate by the entire network. In aggregate, this is a fundamental differentiator between bitcoin and the monetary systems with which bitcoin competes, whether gold or the dollar. And the compensation paid to miners for securing the network and enforcing the network’s fixed supply is exclusively in the form of bitcoin, which further aligns incentives. Individual miners do not have an incentive to allow other miners to arbitrarily create more money, and there is an active disincentive to undermine the credibility of the currency that a miner is being paid to secure, especially given the sole compensation is in units of the very same currency. The economic incentives of the currency (compensation) are so strong and the penalty is both so severe and so easily enforced that miners are maximally incentivized to perform valid work. By introducing tangible cost to the mining process, by incorporating the supply schedule in the validation process (which all nodes verify), and by divorcing the mining function from ownership of the network, the network as a whole reliably and constantly enforces the fixed supply (21 million) of the currency on a trustless basis.

What Secures Bitcoin—Private Keys and Equal Rights

While miners construct, solve, and propose blocks and while nodes check and validate work performed by miners, private keys control access to the unit of value itself. Private keys control the rights to the 21 million bitcoin (technically only 18.0 million have been mined to date). In bitcoin, there are no identities. Bitcoin knows nothing of the outside world. The bitcoin network validates signatures and keys. That’s all. Only someone in control of a private key can create a valid bitcoin transaction by creating a valid signature. Valid transactions are included in blocks, which are solved by miners and validated by each node, but only those in possession of private keys can produce valid transactions.

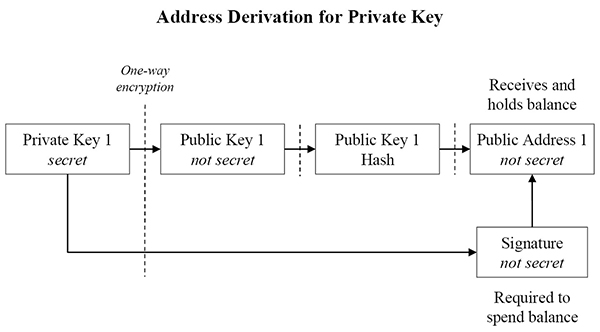

When a valid transaction is broadcast, bitcoin is spent (or transferred) to specific bitcoin public addresses. Public addresses are derived from public keys, which are derived from private keys. Public keys and public addresses can be calculated using a private key, but a private key cannot be calculated from a public key or public address. It is a one-way function secured by advanced cryptography. Public keys and public addresses can be shared without revealing anything about the private keys. When a bitcoin is spent to a public address, it is essentially locked in a safe, and to unlock the safe to spend the bitcoin, a valid signature must be produced by the corresponding private key (every public key and address has a unique private key). The owner of the private key produces a unique signature, without revealing the secret itself. The rest of the network can verify that the holder of the private key produced a valid signature, without actually knowing any details of the private key itself. Public and private key pairs are the foundation of bitcoin. And ultimately, private keys control access rights to the economic value of the network—the units of currency.

It doesn’t matter whether someone has one-tenth of a bitcoin or ten thousand bitcoin. Either and each are secured and validated by the same mechanism and by the same rules. Everyone has equal rights. Regardless of the economic value, each bitcoin (and bitcoin address) is treated identically within the bitcoin network. If a valid signature is produced, the transaction is valid, and it will be added to the blockchain (if a transaction fee is paid). If an invalid signature is produced, the network will reject it as invalid. It does not matter how powerful or how weak any participant may be. Bitcoin is apolitical. All it validates are keys and signatures. Someone with more bitcoin may be able to pay a higher fee to have a transaction prioritized, but all transactions are validated based on the same set of consensus rules. Miners prioritize transactions based on value and profitability, nothing else. If a transaction is equally valuable, it will be prioritized based on a time sequence. But importantly, the mining function, which clears transactions, is divorced from ownership. Bitcoin is not a democracy. Ownership is controlled by keys, and every bitcoin transaction is evaluated based on the same criteria within the network. It is either valid or it is not. And every bitcoin must have originated within a block consistent with the 21 million supply schedule in order to be valid.

This is why users controlling keys is such an important and significant ethos in bitcoin. Bitcoin are finitely scarce, and private keys are the gatekeeper to the transfer of every bitcoin. The saying goes: not your keys, not your bitcoin. If a bank or other third party controls your keys, that entity is in control of your access to the bitcoin network, and it would be very easy to restrict access or seize funds in such a scenario. While many people choose to trust a bank-like entity, the security model of bitcoin is unique. Not only can each user control their own private keys, but each user who does can also access the network on a permissionless basis and transfer funds to anyone anywhere in the world. In aggregate, users controlling private keys decentralize the control of the network’s economic value, which increases the security of the network as a whole. The more distributed network ownership and access is, the more challenging it becomes to corrupt or co-opt the network. Separately, by holding a private key, it becomes extremely difficult for anyone to restrict access or seize funds held by any individual. Every bitcoin in circulation is secured by a private key. Miners and nodes may enforce that only 21 million bitcoin will ever exist, but the valid bitcoin that do exist in circulation are ultimately controlled and secured by a private key.

Bitcoin Versus

In summary, the supply of bitcoin is governed by a network consensus mechanism, and miners perform a proof-of-work function that grounds bitcoin’s security in the physical world. As part of the security function, miners get paid in bitcoin to solve blocks, which validate history and clear pending bitcoin transactions. If a miner attempts to compensate itself in an amount inconsistent with bitcoin’s fixed supply, the rest of the network will reject the miner’s work as invalid. The supply of the currency is integrated into bitcoin’s security model, and real-world energy resources must be expended for miners to be compensated. Still yet, every node within the network validates the work performed by all miners, such that no one can cheat without a material risk of penalty. Bitcoin’s consensus mechanism and validation process ultimately governs the transfer of ownership of the network, but ownership of the network is controlled and protected by individual private keys held by users of the network.

Set aside any preconceived notions of what money is, and imagine a currency system that has a credibly enforced fixed supply. A form of money that cannot be printed and is finite in supply. Anyone in the world can connect to the network on a permissionless basis and anyone can send transactions to anyone, anywhere in the world. Everyone can also independently and easily validate the supply of the currency as well as ownership across the network. Imagine a global economy where billions of people, disparately located throughout the world, can transact across one common decentralized network, and everyone can arrive at the same consensus of the ownership of the network, without the coordination of any central party. How valuable would that network be? Bitcoin is valuable because it is finite, and it is finite because it is valuable—because a currency with a fixed supply is worth securing. The economic incentives and governance model of the network reinforce each other. The cumulative effect is a decentralized and trustless monetary system with a fixed supply that is global in reach and accessible by anyone.

Bitcoin is distinct from all other digital forms of money, including the dollar, because it has inherent and emergent monetary properties. While the supply of bitcoin remains fixed and finitely scarce, central banks will be forced to create more money in order to sustain the legacy credit system. Bitcoin will become more attractive as market participants figure out that future rounds of quantitative easing are not just a possibility but a necessity to sustain an inferior form of money. Before bitcoin, everyone was forced to opt in to this system by default. Now that bitcoin exists, there is a viable alternative. Each time the Fed returns with more quantitative easing to sustain the credit system, more and more individuals will discover that the monetary properties of bitcoin are vastly superior to the legacy system. Is A better than B? That is the test. In the global competition for money, bitcoin has inherent monetary properties that the fiat monetary system lacks. Ultimately, bitcoin is backed by something, and it’s the only thing that backs any form of money: the credibility of its monetary properties.

-

Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (US), “All Sectors; Debt Securities and Loans; Liability, Level [TCMDO],” retrieved from Federal Reserve Economic Data (FRED), Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, 21 August 2019. ↩

-

Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (US), H.4.1: Factors Affecting Reserve Balances of Depository Institutions and Condition Statement of Federal Reserve Banks, Federal Reserve Statistical Release, 26 September 2019. ↩

-

Satoshi Nakamoto, “Re: Bitcoin Does NOT Violate Mises’ Regression Theorem,” BitcoinTalk, Satoshi Nakamoto Institute, 27 August 2010. ↩