Scarce Objects

Abstract

A more intuitive and secure approach to programming with objects distributed across trust boundaries is presented. The approach involves scarce objects and software to support markets in trading scarce objects “rights.”

Introduction

Scarce objects are computational objects that like physical objects are finite and excludable, and force the client to either conserve or consume (use up) their own rights to use the object. References to scarce objects are bearer certificates with two key properties: (1) they are use-once or use-N-times tokens, and (2) like digital cash they are transferred using online clearing using “spent lists” to conserve the number of these scarce object references.

Scarce objects, a.k.a. conserved objects, provide a user and programmer friendly metaphor for distributed objects interacting across trust boundaries. (To simplify the language, I will use the present tense to describe architectures and hypothetical software). Scarce objects also give us the ability to translate user preferences into sophisticated contracts, via the market translator described below. These innovations will enable us for the first time to break through the mental transaction cost barrier to micropayments and a micromarket economy.

A scarce object is a software object (or one of its methods) which uses a finite and excludable resource – be it disk space, network bandwidth, a costly information source such as a trade secret or a minimally delayed stock quotes, or a wide variety of other scarce resources used by online applications. Scarce objects constrain remote callers to invoke methods in ways that use only certain amounts of the resources and do not divulge the trade secrets. Furthermore, scarce object wrappers form the basis for an online economy of scarce objects that makes efficient use of the underlying scarce resources.

Scarce objects are also a new security model. No security model to date has been widely used for distributing objects across trust boundaries. This is due to their obscure consequences, their origins in single-TCB computing, or both. The security of scarce objects is much more readily understood, since it is based on duplicating in computational objects the essential intuitive features of physical possessions. Our brains reason in much more sophisticated ways about physical objects than about computational objects. Scarce objects are thus readily understood by programmers and end users alike. Scarce objects lower mental transaction costs, which are the main barrier to sophisticated small-scale commerce on the Net. Finally, scarce objects will solve for the first time denial of service attacks, at all layers above the primitive scarce object implementation.

The intuitive physical metaphor of scarce objects gives scarce objects the following basic properties:

- Conservation of atomic objects

- Hierarchical composition of objects (analogous to spatial composition)

Closely related to these is a social property of objects critical to the success of economies:

- A clear delineation of property rights and responsibilities. In other words, minimal externalities. Property rights specify residual control and liability over states of the world for which specific obligations or rights are not completely specified in contracts.

Property rights and contracts are highly evolved methodologies for dealing with economic objects and each other across trust boundaries. Scarce object architecture can reuse this working paradigm, because it reuses the mental model of the physical world in which this security paradigm was invented.

With scarce objects, any computation across trust boundaries will have these properties of atomicity, conservation, composition, and the accompanying clear delineation of rights and responsibilities. This model is rather restrictive compared to what we are used to within trust boundaries. However, it will much more readily keep programmers from writing obscurely insecure code, which is easy to do with either ACLs, capabilities, or cryptography. Furthermore, conservation (scarcity) and lack of externalities are the two major assumptions of microeconomics, the study of commercial transactions across trust boundaries. So the scarce objects security model allows us to inherit a rich literature of formal reasoning about such systems.

Scarce objects are, in other words, online commodities. These commodities may represent, typically, rights (or expectations) to services – the right to use an e-mail or news service (or a component of that bundle of rights, e.g. the right to use that service’s e-mail server), the right to upload or cache content, the “right” (here more like an expectation) to have e-mail read (digital postage to prevent spam), etc. Such service rights will usually be limited against the client by time or resource usage or number of invocations. When represented properly, by scarce objects, these services are conserved. Such “rights” or codified expectations are enforced against the server by reputation, by the “physics” of scarce objects, or both, in substitute for or in addition to expensive traditional legal means.

Scarce objects may also represent unique or finite relationships between people and bits – names that correspond to addresses, ownership of trademarks, authorship of content, ownership of certain rights to content (which probably does not, for security reasons, include the right to exclude others from copying the bits), etc.

Scarce objects are not a complete model of computation across trust boundaries. Indeed, there are many smart contracts that can be implemented with cryptographic protocols and/or secure hardware but not with scarce objects. What scarce objects provide is a straightforward basis for implementing, in an intuitively secure way, the anonymous commodity exchange economies formalized in microeconomics in a P2P fashion on the Internet.

Another area important to scarce objects is in reasoning about supply chains. In distributed objects, the call graph is the supply chain. To stretch call graphs across trust boundaries, we must replace rigid client-server relationships with dynamically adaptable customer-supplier relationships. The ideal here is to create a rich toolset of exception handling across trust boundaries. Note that credit risks are a proper subset of supply chain risks. Ka-Ping Yee recently put the supply chain problem succinctly: “be wary of return values from objects you don’t trust.”

Usage Control vs. Access Control

The scarce object architecture suggested here shares some things in common with capabilities, but it secures more kinds of resources and is far more affordable for users and programmers. Capabilities (along with ACLs) are a means of implementing access control. Access control simply deals with the first-level of issue of whether an entity has access or not to a given resource. If an entity has such access, this access is, as modelled or implemented by basic capabilities or ACLs, effectively unlimited in scope. Scarce objects, on the other hand, limit resource usage in three ways – first, by limiting the amount of resources used per invocation, second, by limiting the number of resources used per right (per ticket), and third, by limiting the number of tickets issued.

Scarce Objects and POLA

A raw distributed capability system (i.e. what Mark Miller refers to as “caps-as-data”, to distinguish from capabilities local to the TCB (“object caps”) which have strictly stronger security properties) give out capabilities of infinite duration and unlimited invocations, cannot be considered to be a true principle of least authority (POLA) system. For an object reference to implement POLA, it must be finite in every dimension. A true POLA system never gives out more authority than is necessary and proper to compute the needed function. It is never either necessary or proper to allocate infinite resources, and usually it is not necessary to allocate large resources. The scarce object architecture is the first design for object systems to achieve finite authority, and to allow small allocations for objects that need only small amounts of resources. Scarce objects are thus the first architecture to make true POLA possible.

Scarce Object Architecture

Scarce object architecture depends on a distributed object architecture that makes minimal security assumptions. A good implementation strategy may be therefore to implement this model on top of E. No sophisticated use of its distributecd capability architecture need be made to securely distribute scarce objects; rather the resource-conserving features of scarce objects can be relied on for securing resources.

A bearer right to invoke a scarce object method takes the form of a bearer certificate, or ticket. It can be generic, meaning a right to an N invocations of one of a set of similar or identical objects, or specific, meaning a right to invoke a particular object method in a unique way. Generic rights are fungible and can be transferred unlinkably, using Chaumian blinding.

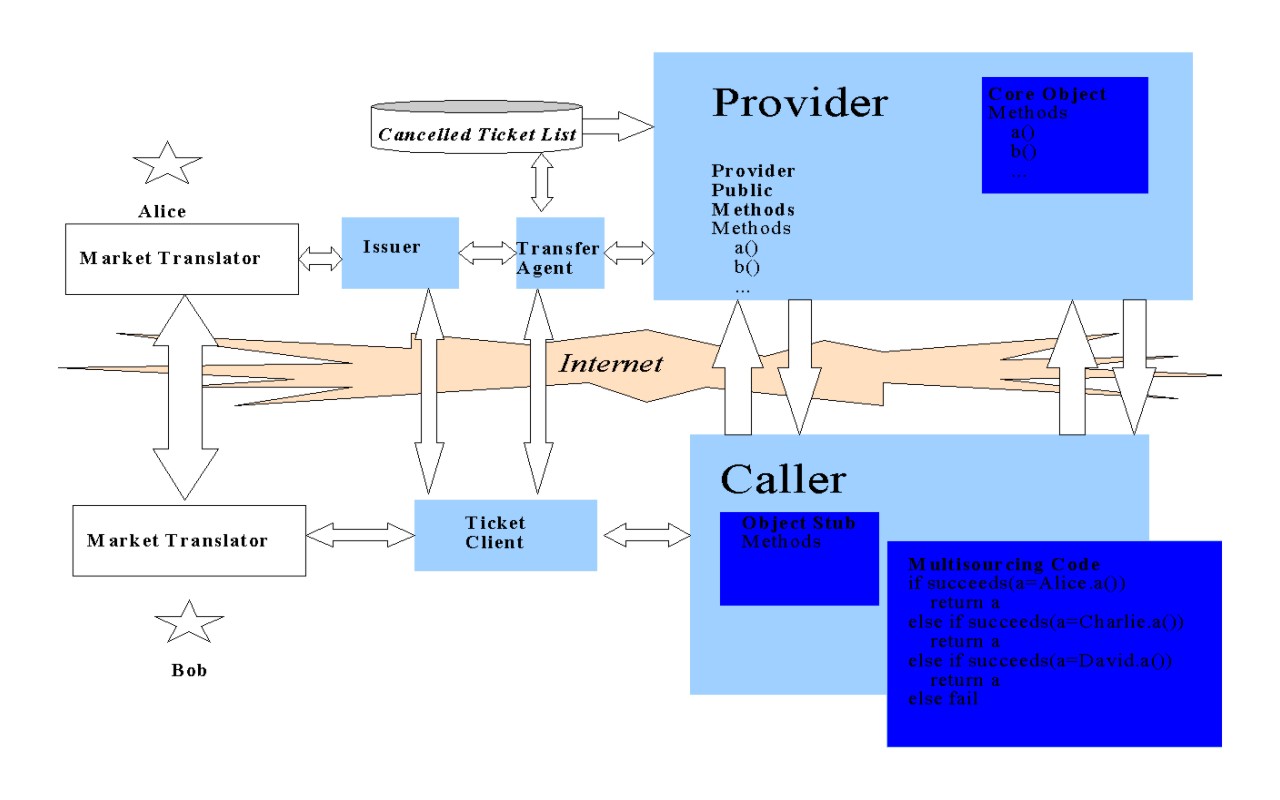

The general steps to build a scarce object are (1) define a normal object, then (2) wrap it in a layer that protects its public methods using tickets. Our sketch of the architecture here describes how this wrapping layer can work.

The wrapping layer involves three different servers: a transfer agent (TA), a Provider, and an Issuer. The Issuer and TA operate like an accountless digital cash mint. The Issuer signs tickets. The TA clears the transfer of tickets for generic rights. Both the Issuer and TA have copies of the private keys (“plates”) corresponding to each issue of generic right. A particular kind of generic right (e.g., a particular denomination of digital coin) can have multiple issues, usually ordered sequentially. Digital cash is a special case: money is the most generic of rights. Here is another example of a generic right, or class of fungible objects: “A queriable SQL database with up to 10 MB of storage, and certain standard response time guaruntees”.

It is a design option whether to combine the Issuer and TA into a single server (thereby reduce exposure of the private key) or keep them separate (thereby enable certain personell controls based on separation of duties). Distributed servers, described below, are an even better way to increase the trustworthiness of Issuers and TAs.

The Provider is responsible for actually holding the object, which can contain unique state. It publishes a signed description of its scarce object method, describing a particular kind of generic right (e.g. in the form of design-by-contract pre- and post-conditions). The issuer and transfer agent then create plate(s) and prepare to issue tickets for the method.

Any or all of these component servers can be distributed, using the methods described here and here. A distributed signature is used to issue tickets (M out of N must sign using a distributed private key for a verifiable signature to be produced). Such distribution greatly reduces exposure to breach of trust and thus lowers the mental transaction costs of reputation tracking.

To implement exclusive transfers, the TA keeps a list of cancelled ticket numbers. A ticket is cancelled whenever it is transferred or used. The Provider instructs the TA when a ticket has been used, or alternatively they both write to a shared list of cleared tickets.

The TA and Issuer see only classes of fungible objects. The Provider and users see particular instances with unique state. In the above example of a database generic right, the Provider sees a database filled with unique information while the TA and Issuer see only the generic description of the database object invocation methods.

In contrast to the servers, the remote user of a scarce object wraps his object invocation stub with calls that trade for needed tickets (again using a market translator), send the tickets as needed with method invocations to those methods’ Provider(s). In some (hopefully many) cases sufficiently identical generic services will be provided by competitors. Where this occurs a “ticket client” may also “shop around” in the sense that if the pre- or post-conditions of the method invocation fail, or if the invocation is otherwise detected as faulty, the ticket client will retry by invoking the competitor’s method.

The Provider server is almost just another ticket client to the TA, which like other clients can transfer or receive tickets. It special role is in informing the TA when tickets have been used thus should be cancelled (or, altrneatively, writing the cancelled ticket number directly to a list of cancelled ticket numbers that it shares with the TA). Only the Issuer can create tickets, and only the Provider can consume them.

At the core of the Provider is the raw object itself, the set of methods that provide the defined services for scarce object clients. The Provider is the wrapper around this object. Besides its gatekeeping, ticket verification, and ticket consumption functions, the Provider can keep track of and inform the Issuer regarding resource usage.

The Issuer in turn is the interface to the micromarket functions, especially the market translator described below. The Issuer may, for example, via a market translator, which incorporates the preferences of the person who operates the Provider, negotiate barter deals in which certain tickets are issued and exchanged for certain other tickets giving rights to invoke the counterparty’s or a third party’s scarce object methods. The negotiations might also be multi-party, i.e. auctions, and secondary exchanges for generic rights may also be developed for scarce object tickets. In turn, the market translator, to enable automated (low mental transaction cost) bartering operations, depends on the existence of reasonably liquid online exchanges of generic scarce object rights.

The TA generates ticket supply only at the behest of the Issuer, and destroys it only at the behest of the Provider. All its own transfers conserve the supply of a particular generic right. The Provider is also responsible for the delivery of service to the client that satisfies the service description (contract, e.g. pre and post conditions), at which time the Provider “deposits” the generic ticket(s), i.e. adds them to the cancelled list.

The Provider issues along with the initial generic rights ticket a signed affadavit, machine or human readable, describing aspects of the object which may be non-exlusive and unique, along with that instance’s ticket number and the public key(s) of the generic right(s) for which it is valid. For example, it might say “a database containing quotes of these two dozen listed stocks as of 12:22 pm Monday”, without actually containing those quotes. Often such description is worth more when bundled with generic exclusive rights, such as the right to a fast response time. The specific rights can elaborate in unique ways upon the generic rights, as long as these elaborations are not taken to define exclusive rights. The generic rights let the TAs garuntee exclusivity to users and conservation of resources to Providers, while the specific rights describe the unique state to any desired degree of elaboration. The Provider must be prepared to service any specific promise it has issued, as long as it is accompanied by the proper conserved generic tickets.

This method of composing specific and generic rights, transferred as a bundle but with exlusive generic atoms cleared by different TAs, allows arbitrarily sophisticated rights bundles, referring to objects with arbitrarily unique state, to be transferred unlinkably. A wide variety of derivatives and combinations are possible. The only restriction is that obtaining rights to specific exclusive resources must either be deferred to the consumption phase, or transferred with online clearing via expensive communications mix.

If the Provider wished to garuntee exclusivity to a specific right, transfer seems to require an expensive communications mix between Provider and transferee, rather than a cheap blinded ticket. For example, “Deep Space Station 60 from 0500-0900 Sunday” or “a lock on autoexec.bat now” demands exclusivity to a specific right, and thus seems to require a communications mix to unlinkably transfer. On the other hand, “A one hour block on DSS-60 in May” and “the right to lock autoexec.bat at some point” are generic and can be transferred privately with the much less expensive blinding, given a sufficient population of other ticket for this class of generic right transfered between the issuance and consumption of a given ticket.

Clients can deal with the TA without a communications mix. They deal with the Provider via a communications mix. If both the initial and final holders failed to do this, the Provider could link them. If just the final holder failed to do so, the Provider could identify him as the actual user of the resource. Thus for full privacy generic transfers are cheap, and nonexclusive transfers are cheap, while specific exsclusive transfers and actually using the object seem to require the expensive communications mix.

Here’s a review of our architecture:

- Composable conserved atomic objects (scarce objects proper):

- Tickets (bearer contracts) are digital certificates, issued by trusted or distributed issuers. Each kind of ticket represents a specific and limited right to a scarce object – for example the right to invoke a method on that object (i.e., use a service provided by that object) up to N times, or up to a certain resource usage limit. Tickets are an essential part of the “object wrapper” that makes a scarce object look and act scarce.

- Distributed issuers, which maintain property titles for certain bearer contracts, namespaces, and other otherwise insecurely conserved publically identifiable entities.

- Design by contract (e.g., detailed specification and testing of pre- and post- conditions) as a central rather than optional part of object programming.

- An advanced scarce object infrastructure may also include:

- Exception handling as bankruptcy or contract breach procedure, to convert rigid client-server relationships into mutually beneficial and dynamically reconfigurable (competitive) customer-supplier relationships, suitable for object invocation across trust boundaries.

- Reputation tracking of the behavior of supply chains. Cryptographic protocols, such as those used to create unforgeable and confidentially auditable transaction logs, can be used to improve the privacy vs. reputation information tradeoff, as long as they are hidden under an intuitively clear metaphor for the reputation of supply chain behavior.

Scarce objects, by creating a simpler and far more intuitive model of computation across trust boundaries, can make the distribution of objects on the global Internet a reality, just as the simplification of hypertext into HTML made the Web a reality.

Diagram of Proposed Scarce Object Architecture

Shopping for Scarce Objects – The Market Translator

The mental transaction cost problem is one that underlies all markets – the mental effort it takes to shop – to map private preferences to prices to decide whether a bundle of rights is worth the cost. In particular this problem presents a severe barrier to micropayments and market-based resource allocation for networks and computers.

The market translator is aimed squarely at solving, for the first time, this problem for Internet commerce. A market translator both enables and depends on online micromarkets to automate resource allocation among scarce objects. It will do so by enabling the following:

- Expression of preferences – and their translation into codified expectations, or rights and duties – with both user-friendly GUIs (“source language”) and a formal contract language (“target language”), and translation between them.

- The bundling and recombination of sophisticated structures of rights.

- The input of user preferences, and their translation from human expressible to computer readable form.

The Problem

The problem of “translating” between bearer contracts (which represent and secure rights to scarce objects) can be cast as a problem of translating between monetary currencies. For our purposes, a “currency” in a scarce object economy is simply any kind of bearer contract used for holding and transferring wealth, rather than for consumption by the holder. It is thus a “collectible” (or “intermediate commodity”, to use Carl Menger’s term). The market translator, incidentally, makes the O(n^2) prices in a barter economy, versus O(n) in a monetary economy, a far less important distinction.

So let’s look at currencies. Let’s say small businessman Alice is negotiating cyberspace contracts with Bob, Charlie, etc. Typical of international contracts, terms can be denominated in a variety of ways. These are potentially unreliable: Joe-Bob’s remailer postage, U.S. Federal Reserve Notes in their 1970s mode (or in 2003), Seychelles gold cache warehouse receipts, “Asian Tiger” currencies in 1997, and so on.

Unreliable currencies can play havoc with:

- contractual terms of long duration

- long term accounting of one's own budget in a consistent manner.

Each problem interferes with potential solutions to the other. On the one hand, picking one single best currency for all contracts concentrates risk. In some cases there is nothing close to a reliable currency, and in any case diversification is preferable. Without hedging Alice remains exposed to risks that more sophisticated traders can easily hedge.

Another way of looking at it: there are no issuers in the world who are 100% trustworthy and 100% reliable. Lacking a security protocol to ensure that a currency retains its value, Alice needs risk management.

On the other hand Alice, to plan her (personal and/or small business) budget and properly express her preferences, needs a simple, consistent long-term unit of account. Budgeting with a single fluctuating currency is bad enough, but if Alice denominates different expenditures and revenues in different currencies, her budget becomes an inconsistent mess. It’s also unreasonable to ask a non-financial professional to worry about the finer points of exchange rates, hedging, etc.

What is Alice to do? Old answer: Alice either hires, at a cost of both money and privacy, an accountant or financial planner, and may gain a few crude improvements. Mostly, she’s out of luck: small businessmen have left most international trade to big corporations, whose finance officers partake in sophisticated hedging strategies.

Proposed new answer: use a market translator to help Alice draft her contracts. This market translator should be useful for both normal law-enforced contracts and untraceable self-enforcing contracts, where the latter are feasible. In the following post I will sketch how a market translator can work.

A Solution

Automatic currency conversion, as done today by some credit cards and ATM machines, is a useful primitive kind of market translation. The casual reader (and user) can think of the market translator (MT) as a fancy kind of automated currency convertor, and get the basic gist of it. The MT serves to convert, hedge, and in general restructure the payment terms contracts negotiated in any manner.

Our main novelty is to account for personal budgets, not in terms of any external standard of value, but rather in terms of personal accounting units (PAUs). PAUs correspond to what Alice can express of her personal utility. The MT determines Alice’s static and and temporal preferences from the budget Alice already maintains (for example, her small business budget in Quicken). Additional preference specification forms may be provided beyond those of a normal budgeting program. For example, Alice’s software preference settings, her behavior with keyboard and mouse, and similar clues might be usefully interpreted as economic preferences, for example with regard to where to allocate scarce screen real estate and network bandwidth.

For convenience Alice’s PAU might correspond to the local currency most commonly used by Alice. If most of Alice’s budget items deal with online contracts negotiated via MT, then using the local currency is by no means necessary, and is undesirable if that currency is unstable.

Here is a diagram showing Alice and Bob negotiating a contract using their market translators:

Alice Bob

Draft Contract, "source" Draft Contract, "source"

(Alice PAUs) (Bob PAUs)

^ ^

| |

MT MT

| |

v v

Draft Contract, "target" <-----> Draft Contract, "target"

One mode in which the MT can be used is to have Bob offer a take-it-or-leave-it binary contract, corresponding to the current retail practice of take-it-or-leave-it prices. In the mode pictured above, Alice and Bob negotiate back and forth. The negotation of the source contract terms will usually be manual. The “source language” will typically be a human readable GUI, while the “target” will be a standard formal contract language. If Alice and Bob can input preferences leading to automated negotiations, then a “shopping bot” and “catalog bot” respectively may be used. This is a layer above and beyond the scope of the MT. The MT is only a “shopping bot” in the restricted but important area of contracts composed of atomic bearer contracts – rights to scarce objects – to the extent that the price relationships between these bearer contracts are available from quoted markets.

The MT acts like a computer language compiler. But it translates both ways, and in real time as Alice and Bob negotiate payment terms. So, for example, Alice changes a term in her contract, proposing to pay fewer Alice-PAUs for Bob’s services. Her MT translates this into a series of payments and hedges: a sophisticated synthetic contract as obscure to Alice and Bob as binary code is to many programmers these days. This synthetic is constructed out of liquid market securities (bearer contracts) and derivatives of low transaction cost. A synthetic contract is naturally represented as a composite object, a part-whole hierarchy composing primitive contractual “atoms”, such as securities and derivatives.

Bob’s MT reverse-translates the actual market terms into Bob-PAUs. Although they each agree to different looking amounts of payment, the visible structure besides amounts and the complete underlying contract is the same. They can be confident that when their preferences have been satisfied, their minds have met and they can commit to the contract.

As a result, both Alice and Bob see the contract in terms of their own consistent personal utility units. All consideration of exchange rates, inflation risks, and so on is handled by the MT.

Alice and Bob’s MTs can make side conversions, hedges, and restructurings to balance their portfolios. These side hedges are not revealed to each other. Any binary terms which can be side hedged can be made almost arbitrarily distant from what Alice and Bob prefer financially. Thus Alice and Bob need not reveal their financial preferences to each other.

(Note: For contracts with delayed payment terms, Alice and Bob determining the credit risk caused by each others’ credit exposures is an important problem, but beyond the scope of the MT as I have described it).

The whole set of Alice’s contracts with all her counterparties constitutes her complete portfolio – not merely a segregated investment portfolio, but a complete portfolio encompassing all her finances. This portfolio is is represented as a composite of composite contracts, and forms the basis for all of Alice’s financial planning, and for the automated portfolio rebalancing activity of the MT.

The main data structure representing the contracts for analytical purposes is the chance/choice decision tree. This tree has two kinds of nodes, “chance” nodes which iterate through all material possibilities, and “choice” nodes where the optimal choice is made. The result is the expected value of a set of contractual terms. The trees can represent a large number of contracts with low resolution (lots of pruning and heuristics), or a simple contract with high resolution (all possibilities considered). Desktop computers are or will soon be fast enough to search through thousands of contingencies, and synthetic contracts composed of hundreds of atomic contracts, with delays less than Internet latencies. So the binary contract can be a very sophisticated synthetic, as long as its analysis is fully automated, and still conserve mental transaction costs.

Conclusion

The MT relies on online, automated exchanges hosting liquid markets for fixed income securities and derivatives. These markets reveal the information the MT needs to properly hedge currencies. Market makers and arbitrageurs maintain these markets, ensuring the most accurate information on risk premiums, yield curves, and so on is available to MTs. Some information not automatically derivable from market prices might be made available online by financial consultants, in a standard format, downloadable by MTs for a fee.

The source contract is normally negotiated and closed manually, as per normal shopping. The MT is a a “shopping bot”, but only in the very restricted but important realm of finance related to payment terms. Since

- Alice has sufficiently input her financial preferences for risk and time value, via her budget program and/or specialized forms, and these preferences apply to all the payment terms used by the MT,

- All the information necessary to determine the risk posed by a payment term is available online (usually in the form of market prices for securties and derivatives, but also from online financial consultants who publish financial news in MT-readable format), and

- By assumption all the hedging securities and derivatives can be automatically purchased or sold by the MT,

there should be no need for manual intervention in the hedging translation process. If such manual intervention is required, the system very quickly loses its appeal for most users.

If the preference or market information is not available, or the securities and derivatives exchanges are not available, the market translator can revert back to simple automated currency conversion.

The market translator thus solves a vexing problem faced by multinational small business, the hedging of payment terms using potentially unreliable currencies. More generally, the market translator built on a scarce object architecture will lower the mental transaction cost barrier to micropayments and micromarkets. It will translate skills and preferences into microrights and microduties for use in fine-grained allocation of resources and services – whether online e-mail accounts, online game collectibles, screen real estate, network bandwidth and caching, or a variety of other network objects which, thanks to scarce object architecture, become economic objects.