Bitcoin Fixes This

First published on Unchained Capital Blog

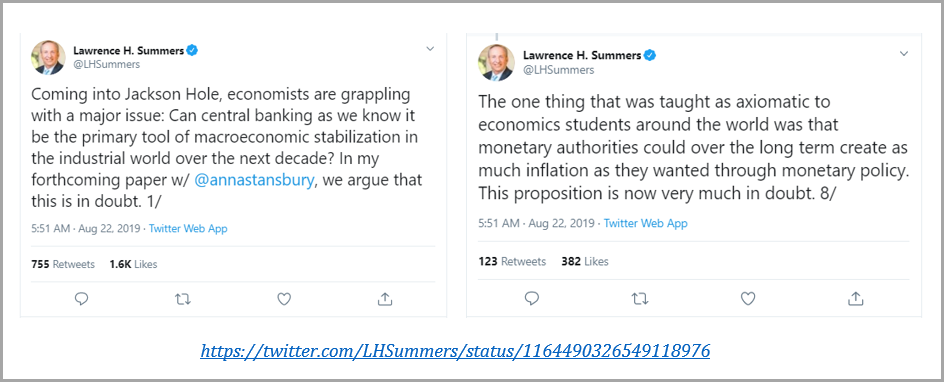

This past week marked that time of year when global central bankers, establishment economists and CNBC, et al. descend on Jackson Hole, Wyoming to discuss the systemic issues that plague our economy. Never seeming to find an answer but constantly in search of it; it is the perennial Jackson Hole dilemma. There is always much fanfare and this year was no different. The whole spectacle may have been highlighted by Lawrence Summers, former U.S. Treasury Secretary and former President of Harvard University. In a 28-part twitter thread, Summers questioned a number of foundational assumptions made by the establishment economic mainstream, of which he is a resident member. In the game of Marco Polo, Summers is getting warmer but he’s still on the wrong side of the pool. Identifying symptoms of the problem maybe, but as with most mainstream economists, the obvious question is never asked. Could the whole apparatus of central bank policy be the root cause of the problem rather than the ever-elusive solution?

The baseline question from Summers: can central banking as we know it be the primary tool of macroeconomic stabilization in the industrial world over the next decade? Summers doubts that it can, but what if the better question were: is central banking the primary cause of macroeconomic instability? Since the financial crisis, quantitative easing has been the primary tool central banks have used in an attempt to stabilize the economy and to manufacture inflation. The playbook is as follows: increase the money supply, reduce interest rates and reflate asset values such that existing debt levels can be sustained and more debt can be created.

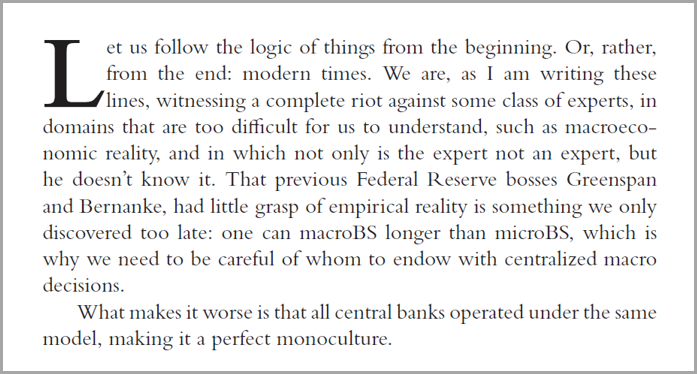

However, despite record low interest rates, the global economy has once again begun to deteriorate and the effectiveness of quantitative easing is naturally being questioned by many. As Summers notes, what has long been taught as axiomatic is now very much in doubt. Contrary to popular belief, the function of quantitative easing actually creates the instability it seeks to avoid. When understanding its base operation, it becomes clear that quantitative easing has always been a fool’s errand. As Nassim Taleb writes in the foreword to The Bitcoin Standard, the macroeconomic experts are not only not experts, they don’t know it either.

“The risk that the economy has entered a substantial downturn appears to have diminished over the past month or so.”

History has consistently established that the experts are limited in the field of their own expertise, yet policies such as quantitative easing continue to be pursued, largely because macroeconomics and central banking is a monoculture, as Taleb describes. The mainstream policy position starts with the assumption that central banking is core to the function of an economy; then debate centers on what levers to pull and how best to manage the economy via central bank planning. Active management of the money supply via quantitative easing is taken as a given; it’s a question of how much and when, rather than if.

However, there remains an opposing economic view which argues that the very function of a central bank and the active management of the money supply is harmful to the economy. The opposing viewpoint cannot practically co-exist within a central bank because it is antithetical to the very function, which is why the monoculture exists and why a different course is never charted. Ultimately, the economic debate played out over the course of the 20th century and ended with what has become the current mainstream position. The consequence has been an economic system that relies heavily on monetary debasement and credit creation, both of which are achieved through quantitative easing.

Now that bitcoin exists, it is no longer merely the subject of an intellectual debate. Instead, we now have two competing monetary systems that present great contrasts: one attempts to create stability through active management of the money supply, while the other tolerates interim volatility in the interest of maintaining a fixed supply. For the last ten years, the bootstrapping upstart has been gaining ground on the incumbent system, as demonstrated by its adoption and steadily increasing value relative to other currencies. Opting in to bitcoin means opting out of quantitative easing, and while it may be a volatile path, the long-term trend will continue because central banks continue to pursue the very policy tool which bitcoin prevents.

While attempting to be a source of macroeconomic stabilization, central bankers inadvertently create instability through the manipulation of the money supply. By manipulating the supply of money, all global pricing mechanisms become distorted. As Hayek describes in “The Use of Knowledge in Society”, the price mechanism is the greatest distribution system of knowledge in the world. When the price mechanism becomes distorted, false signals are distributed throughout the economic system and the result is an imbalance between supply and demand which ultimately creates instability and fragility. Today, this instability has primarily been created and sustained as a function of quantitative easing. The financial crisis made it clear that the size of the credit system was both unstable and unsustainable; rather than allow the system to naturally deleverage, the Fed reflated asset prices and induced further credit expansion, such that existing debt levels could be sustained. Practically speaking, the central banking approach to solving a problem of too much debt was to induce the creation of even more debt, which was the original source of instability. Fortunately, bitcoin fixes this.

What is quantitative easing?

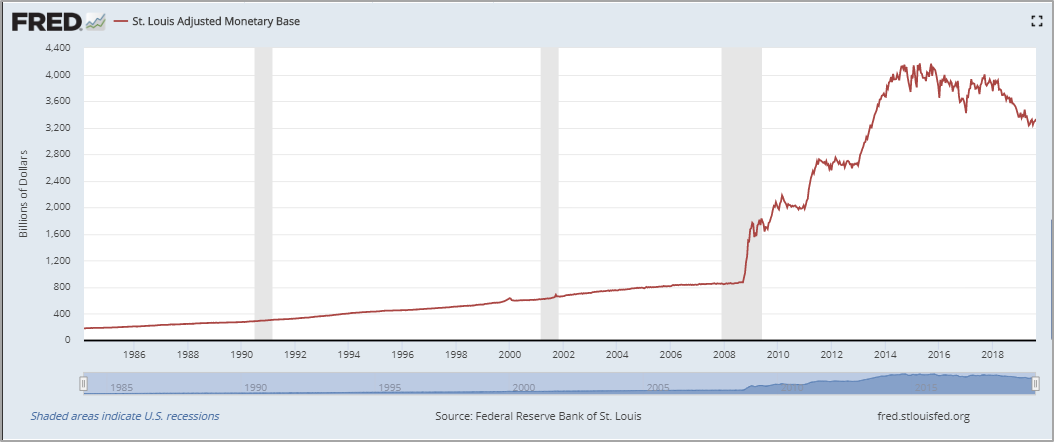

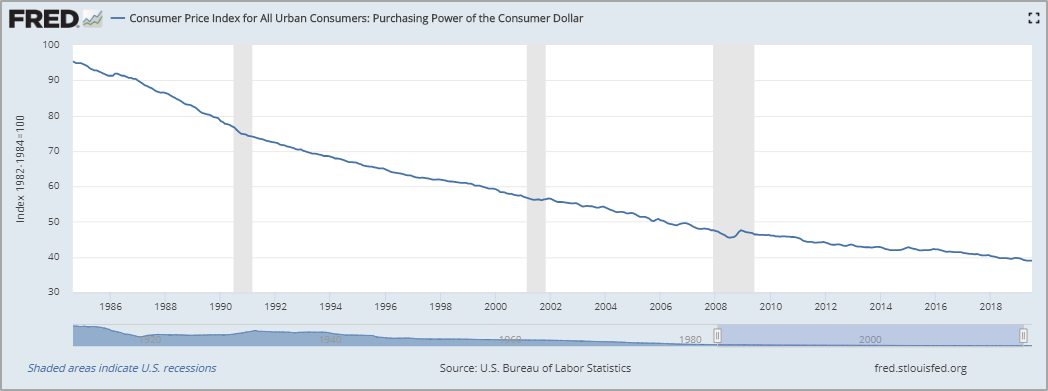

In the most simplistic terms, quantitative easing is a technical term that describes how the Federal Reserve creates new dollars. It isn’t technically “printing money,” but it is functionally the same. The Fed digitally creates new digital dollars on a ledger (literally out of thin air) and uses those dollars to purchase financial assets, such as U.S. treasuries (government debt) or mortgage-backed securities. Following the financial crisis, the Fed introduced $3.6 trillion new dollars into the banking system via QE, quintupling the size of its balance sheet. As a net effect, more dollars exist within the banking system in the form of bank reserves and those reserves can then be used to lend or to purchase other assets. In simple terms, more dollars exist, which causes the value of each individual dollar to decrease.

Quantitative easing is the root cause of why your dollar purchases less tomorrow; however, the effects of quantitative easing are transmitted gradually through the economy via the expansion of the credit system. Said another way, quantitative easing is designed to allow banks to expand credit; for every dollar that is created through quantitative easing, the credit system can expand by multiples of each dollar added. This incremental credit (think auto loans, mortgages, student loans, etc.) is then used to purchase goods in the real economy, which causes the prices of goods to rise and the value of the dollar to decline on a relative basis.

Does quantitative easing work?

The short answer is no. While many believe that quantitative easing was necessary, it merely kicked the can down the road and guaranteed more QE would be necessary in the future. The root cause of the crisis was a financial system that had become far too leveraged. At the time of the financial crisis, every dollar in the banking system had been leveraged and lent 150:1 (see Fed Z.1 & H.8 reports). There was too much debt and too few dollars, and the degree of leverage was only made possible as an indirect function of the Fed sustaining economic imbalances. With every recessionary business cycle in the decades leading up to the crisis, the Fed increased the supply of dollars to lower interest rates and to induce credit expansion. Rather than allow the system to course correct as a natural market function, the Fed’s continual response was to reflate asset values by increasing the money supply such that existing debt levels could be sustained and more credit could be created.

Through this function, the Fed inadvertently created the instability that existed in the financial system in 2008 because it created the environment which allowed for an unsustainable degree of system leverage to accumulate over the course of decades. While it has pursued similar policies for decades, the financial crisis created an environment that triggered a more drastic response from the Fed. Practically speaking, the Fed needed a bigger boat and in response to the market turmoil, it increased the supply of dollars by $3.6 trillion in order to stave off an impending financial collapse. This time was different; while the subprime crisis steals the headlines, the real issue was the cumulative effect of sustained imbalances in the credit system which had accumulated over many cycles and the overall degree of system leverage.

In the Fed’s economy, the credit system has become the marginal price mechanism. And because the Fed has a mandate to maintain price stability, it must implicitly maintain the size of the credit system in order to sustain general price levels. During the financial crisis, the credit system began to contract and asset price levels rapidly declined in a disorderly fashion. In order to reverse the impact, the Fed was forced to drastically increase the money supply (quantitative easing) in an effort to maintain the size of the credit system. Even after the height of the crisis, the Fed determined it was necessary to add trillions more in new dollars to continue to support a languishing system, despite acknowledging the limitations of its monetary policy tools. This is the Fed’s catch-22; even when it seemingly knows betters, the Fed’s default position is to err on the side of more quantitative easing, not less.

“I’m perfectly willing to accept the argument that monetary policy is not the main tool, that this is not the main thing wrong with the economy, but it’s our duty to do what we can, to be palliative, to help where we can, even if we can’t solve fiscal, structural, and other problems.”

“I don’t think it is literally the case that monetary policy is completely ineffective. I think we can see the effects on financial markets, which in turn must be affecting wealth, confidence, and some other determinants of spending and production. To the extent that transmission is weaker, that could be used to argue for more stimulus rather than less stimulus.”

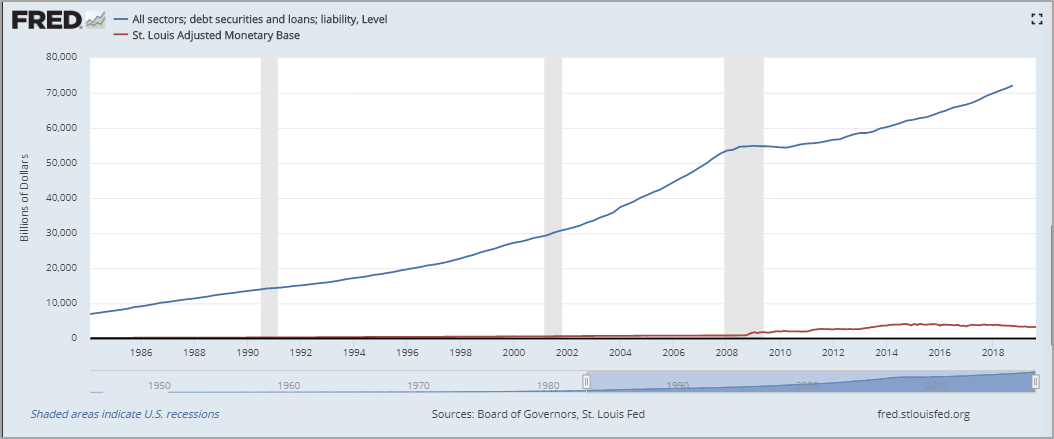

By responding with quantitative easing, the Fed induced a credit system already saddled with too much debt to expand massively. Today, the U.S. credit system supports approximately 73 trillion of fixed maturity debt (system wide), which represents an increase of 20 trillion (+40%) above pre-crisis levels (Fed Z.1 report, pg. 7). This debt is stacked against only $1.7 trillion of actual dollars that exist within the banking system (Fed H.8 report). As a consequence, there remains far too much debt and too few dollars. Because QE induces the creation of trillions more in debt, it is more like heroin than an antibiotic; the more that is applied to a financial system, the more dependent on it that system becomes and the worse off when it is removed.

Bitcoin Fixes This

Prior to 2009, everyone was forced to opt-in to this system, and there was not a viable off-ramp. This is ultimately the option that bitcoin provides, and it exists largely as a response mechanism to global QE. There is no more simple explanation to the question of why bitcoin exists. While bitcoin would have presented a superior alternative even in the absence of quantitative easing, the global monetary debasement which occurred in response to the crisis sharpens the contrast. It is this contrast that makes the mere existence of bitcoin far more intuitive than it otherwise may be. Bitcoin literally exists because some highly intelligent individuals identified a problem and set the wheels in motion to create a solution. However, bitcoin practically exists because it presents a fundamentally better solution to the problem of money.

Because of the leverage that remains inherent in the existing financial system, future QE is not merely a possibility; it is a certainty. Future QE from the Fed, and central banks all over the world, is a “when” not “if” question. The credit system was unstable and unsustainable in 2008. As a function of QE, it has expanded massively and now supports $20 trillion more debt in the U.S. alone. Every time the Fed, or any central bank, announces subsequent rounds of QE, that is the reinforcing market signal of why bitcoin exists. It is the choice between holding a form of currency that is continually and systematically debased by central banks or a form of currency with a fixed supply that is unmanipulatable. Bitcoin is the check, balance and ultimate opt out path to the problem QE presents.

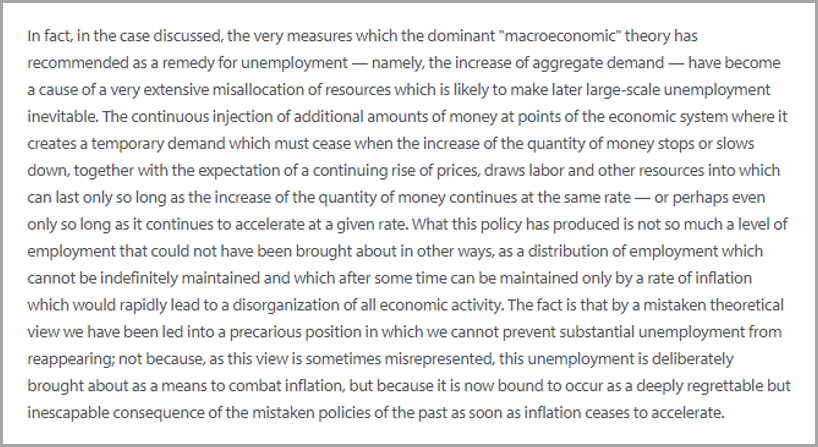

In “The Pretense of Knowledge”, a speech delivered by Friedrich Hayek at the ceremony awarding him the Nobel Prize in economics in 1974, he articulates the first principles of why the disparate knowledge of all market participants is greater than that which any single mind possesses. It is through this reasoning that he explains why the dominant macroeconomic theory and monetary policy which guides central banks is inherently flawed. And, why the policy tools used by central banks, particularly quantitative easing, create more harm than good. I highly recommend reading the full speech as it provides the counter-narrative to the monoculture of today’s economic policy making. Our current system entrusts the allocation of trillions of dollars to just a few individuals. It is not that these individuals lack a significant amount of knowledge; instead, it is that any small group of individuals necessarily possesses far less knowledge than the hundreds of millions of individuals that actually make up an economy.

By attempting to manage an economy through the manipulation of the money supply, the knowledge of many is not only replaced by that of a few; instead, the collective knowledge base as a whole becomes distorted. The mechanisms that govern supply and demand can no longer function efficiently, which creates imbalances that can only be sustained so long as the market remains manipulated. In the end, the ultimate negative impact to the economy is far greater than it otherwise would have been in the absence of central bank intervention. The financial crisis is patient zero and the quantitative easing response has only left us in a more precarious situation today. The first order impact is the devaluation of the currency, but the ultimate impact is the deterioration of the underlying economic structure. Bitcoin is designed to fix this but no one should expect a seamless or painless transition away from a system saddled with decades of accumulated imbalances.

Bitcoin creates a system that allows for undistorted economic activity, and it achieves this through a fixed monetary supply, which is ultimately governed by a market consensus mechanism. It is through this consensus mechanism that bitcoin dispenses with the need for conscious control of central bankers, instead relying on the distributed knowledge of all market participants. It is also completely voluntary. If you like your financial system, you can keep it (for now at least). However, monetary systems tend to one medium so if a critical mass converge on bitcoin as the most credible long-term store of value, it may become less of a choice in the future. As individuals increasingly opt in to bitcoin, it will only make the issues present in the existing system more evident, which likely accelerates the need for quantitative easing. The greater the inclination to store wealth in bitcoin, the lower the demand to store wealth in the assets that support the existing credit system. In essence, an increasing shift to bitcoin will directly impact the system-wide credit impulse, which will accelerate the need for the legacy financial system to rely on quantitative easing to sustain itself.

Bitcoin may be the sly round about way around the Fed’s economic system, but it comes at the direct expense of the legacy system. And, the interim consequence of the shift to bitcoin may very well be macroeconomic volatility. Bitcoin may be mistakenly blamed for the ills of the legacy system but really, withdrawal is just a painful and necessary process. The Jackson Hole crowd may not like this; however, positive externalities will be waiting on the other side. And besides, it’s in the hands of the free market now.

“I don’t believe we shall ever have a good money again before we take the thing out of the hands of government, that is, we can’t take them violently out of the hands of government, all we can do is by some sly roundabout way introduce something that they can’t stop.”

Views presented are expressly my own and not those of Unchained Capital or my colleagues. Special thanks to Phil Geiger, Adam Tzagournis and Will Cole for reviewing and for providing valuable feedback. If interested in reading more about quantitative easing and the financial crisis, I wrote a longer research piece in 2017 on the subject (see here).