Chapter 16

International Banking Systems, 1871–1971

1. The Classical Gold Standard

By the end of the 1860s, only the U.S. and some major parts of the British Empire had been on the gold standard. In the United Kingdom, gold had been monopoly legal tender since 1821, the United States had a de facto gold standard after the Coinage Act of 1834, and Australia and Canada followed suit in the early 1850s. All other states had a silver standard, bimetallic standards, or legal-tender paper monies. Then the German victory over France in the war of 1870–71 ushered in the era known as the classical gold standard. The new German central government under Bismarck obtained a war indemnity of 5 billion francs in gold. It used the money to set up a fiat gold standard, demonetizing the silver coins that had hitherto been dominant in German lands. Four years later, the financial lackey of Bismarck’s Prussian government—the Prussian Bank—was turned into a national central bank (its new name, the Reichsbank, was a marketing coup). Thus the Germans had copied the British model, combining fiat gold with fractional-reserve banking and a central bank, whose notes obtained legal-tender status in 1909.[1]

Why gold? Why did the Germans not set up a silver standard or join a bimetallist system such as the Latin Currency Union?[2] Several factors came into play here. One might mention in particular the influence of “network externalities” that weighed in favor of gold. On the one hand, gold was the money of Great Britain, the country with the world’s largest and most sophisticated capital market. On the other hand, several major silver countries including Russia and Austria had suspended payments at the time of the German victory. Thus silver offered no advantages for the international division of labor, whereas gold did.[3] Moreover, one should not neglect that silver, the only serious competitor for gold among the commodity monies, has one grave disadvantage from the point of view of a government bent on inflationary finance. Because of its bulkiness, the use of silver entails higher transportation costs, which makes it less suitable than gold for fractional-reserve banks trying to quash systematic bank runs through cooperation.

Virtually all other Western countries now followed suit. The establishment of international “unity” in monetary affairs required no elaborate justification. It was perfectly congenial to the cosmopolitan spirit of the times, nourished by several decades of free trade and burgeoning international alliances and friendships. Thus it served as the perfect justification for a further massive intervention of national governments into the monetary systems of their countries. Legal privileges were abrogated in all other branches of industry. Monopoly was a curse word more than ever before. But it seemed to be tolerable as a means for that noble cosmopolitan end of international monetary union. By the early 1880s, the countries of the West and their colonies all over the world had adopted the British model.[4] This created the great illusion of some profound economic unity of the western world, whereas in fact the movement merely homogenized the national monetary systems. The homogeneity lasted until 1914, when the central banks suspended their payments and prepared to finance World War I by the printing press.

On the positive side, it could be claimed that the classical gold standard eliminated the exchange-rate fluctuations between gold and silver and thus boosted the international division of labor. It is somewhat difficult to evaluate the quantitative impact of this advantage. Let us therefore merely observe that exchange-rate fluctuations between gold and silver are negligible when compared to the fluctuations between our present-day paper monies.

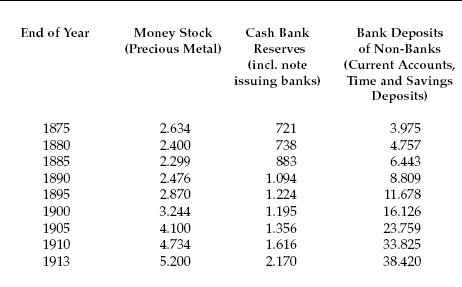

On the negative side, the classical gold standard created a considerable fiat deflation due to the demonetization of silver. From 1873–1896, prices fell more or less sharply in the countries that had adopted the gold standard first (U.K., U.S., Germany) because of the gold exports that resulted when other countries followed their example and established a gold-based currency too.[5] This in turn created pressure to reinforce the practice of fractional-reserve banking, both on the level of the central banks and on the level of the commercial banks (see Table 3). Above we have analyzed the inherent fragility of fractional-reserve systems and seen that this fact, because it is known to the bankers, incites them to postpone the crisis through cooperation. Under the classical gold standard, this was the case too.[6] Yet for the reasons we have discussed in some detail, cooperation cannot stop the dynamics of inflation inherent in the system itself. Sooner or later this process finds its limits and the fractional-reserve banking system collapses or is transformed into something else. The classical gold standard was no exception. It was spared collapse or transformation into a gold-exchange standard only because another lethal accident (WWI) killed it before it could die from its own cancer. World War I delivered the pretext for the suspension of payments. But sooner or later suspension would have become inevitable anyway. The system did not limit inflation. All of its main protagonists—the national central banks—were fractional-reserve banks, and under their auspices and protection the commercial banks happily trotted down an inflationary expansion path.

Table 3: Evolution of the Money Supply in the German Reich (in Mill. Mark)

The glory of the classical gold standard was that it demonstrated, for the last time so far, how a worldwide monetary system could emerge without political scheming and red tape between national governments. They adopted it independently of one another. There was no treaty, no conference, and no negotiation to bring it about. However, as we have seen, even in this respect the classical gold standard was rather imperfect. It did after all not result from the free choice of free citizens, but from the discretion of national governments. It gave the world a common monetary standard—gold—but this standard sprang from the coercive elimination of all alternative monies. Its ultimate effect was, not to give the citizens of the world an efficient monetary system, but to deliver a pretext for national governments to finally bring the monetary systems of their countries under their control. The classical gold standard was therefore hardly a bulwark of liberty. It was a crucial breakthrough for the societal scourge of our age— government omnipotence.

We have to stress these facts because many advocates of the free market believe the classical gold standard was something like the paradise of monetary systems. This reputation is undeserved. The classical gold standard differed only in degree, not in essence, from its successors, all of which have been widely and deservedly criticized in the literature on our subject.[7]

2. The Gold-Exchange Standard

The expression “gold-exchange standard” is usually applied to the organizational set-up of the international monetary system that existed between 1925 and 1931. But this organization was thoroughly unoriginal. It had existed before; in fact it had been part and parcel of the classical gold standard. Rather, the new system that was created in the latter half of the 1920s was characterized by the more or less explicit objective of most of its participants to strive for monetary expansion (inflation) through international cooperation.[8]

Under the classical gold standard, each central bank was responsible for making sure that its notes could be redeemed into gold. The central banks of Great Britain, France, Germany, Switzerland, and Belgium (and later of the U.S.) kept their entire reserves in gold. These reserves were supposed to be large enough for them to survive emergency situations. Things were different in the realm of the commercial fractional-reserve banks that operated within the national economies of these countries. The commercial banks usually kept the lion’s share of their reserves in the form of central banknotes and only held extremely low gold reserves. The latter were needed only for emergency situations, and in such cases the commercial banks had also learned to rely on the reserves of their central bank. In some countries, this practice predated the classical gold standard by quite a few decades. For example, it was already the practice of the English country banks in the first half of the nineteenth century. They kept Bank of England notes as part of their reserves and, in times of great strain on their gold reserves, often redeemed their own notes, not into gold, but into notes of the Bank.[9]

Under the classical gold standard, most central banks adopted exactly the same scheme. The central banks of Russia, Austria-Hungary, Japan, the Netherlands, and of the Scandinavian countries, as well as the central banks of British dominions such as South Africa and Australia redeemed their own notes not only in gold, but also in notes of the more important foreign central banks. Still other countries such as India, the Philippines, and various Latin American countries held their reserves exclusively under the form of foreign gold-denominated banknotes.[10] The purpose of the structure is patent. The pooling of gold reserves in a few reliable central banks allows a larger inflation of the worldwide note supply than would otherwise have been possible. The pitfall is that it places the entire responsibility of keeping sufficiently large reserves on a small number of “virtuous” fractional-reserve banks. The latter have a reason to accept this burden, however, because their virtue gives them political power over the other banks, especially in times of crises.

The significance of the gold-exchange standard of 1925–31 was that it elevated this practice of coordinated inflation into a principle of international monetary relations.[11] Only two banks—the American Fed and the Bank of England—were to remain true central banks, but this time they would be the central banks of the entire world. All other national central banks should keep a more or less large part of their reserves in the form of U.S. dollar notes and British pound notes. This would assure the possibility of inflationary expansion for all banks. The expansion rate would be comparatively low in the case of the central banks of the U.S. and the United Kingdom; but the latter would be repaid in terms of political power.[12]

Thus from the very outset, the gold-exchange standard was meant to encourage irresponsible behavior. Designed to facilitate inflation, it was not surprising that it lasted only six years. It collapsed when, in the wake of the 1929 financial crisis on Wall Street, various governments turned to protectionist policies (most notably in the U.S.) or imposed foreign exchange controls (as in Germany, Austria, and a number of Latin American countries), thus choking off international payments and making it impossible for the Bank of England to replenish its reserves. As a consequence, the Bank suspended payments in September 1931. The other central banks followed suit, plunging the world into a regime of fluctuating exchange rates that lasted until the end of World War II.

3. The Bretton Woods System

In July 1944, at a conference in Bretton Woods, New Hampshire, the western allies agreed on an international monetary system that should be instituted after their victory in World War II. As one might expect, the point of the new scheme was to make the production of banknotes more “flexible” (that is, expansionary) than ever before. How? The trick was to pool the gold reserves of the entire world into just one large pool. There was to be only one remaining bank that would still redeem its notes into gold—the U.S. Fed—while all the other central banks would keep the bulk of their reserves in U.S. dollars and, accordingly, redeem their own notes only into dollars.

Thus the Bretton Woods system was a gold-exchange standard writ large.[13] It was far more expansionary than its predecessors because it applied the pooling technique to a far greater extent. Under the classical gold standard, there were many gold pools in the world economy, because the different nations kept their gold pools separate from one another (in the national central banks). Under the gold-exchange standard, the number of gold pools had declined very substantially, and the point of the Bretton Woods system was to go the way of pooling almost to the end. It is true that the system did not exhaust its full potential for inflation. When it collapsed in 1971, there were still substantial gold pools in central banks other than the Fed; thus a further centralization of these resources could have kept the system going for a while. In any case, the Bretton Woods system was so far the most ambitious attempt ever to create an international monetary system through a cartel of fractional-reserve banks.

We have repeatedly highlighted the fact that pooling creates political dependency. In the present case, the other central banks and their governments became dependent on the good will of the Fed, which administered the world gold pool and which therefore had the power to allocate the world’s banknotes—U.S. dollars—at its own discretion. Thus the crucial question is: Why did the other national central banks consent to the centralization of the gold pool, and thus to the centralization of power? Part of the answer is that it might be useful to have an international monetary system (stable exchange rates among the national currencies) even if this entails some measure of dependency. But there were also other aspects that came into play in the present case.

The historical accident was that during World War I and its long aftermath, the United States became a safe haven for European gold. This predestined the Fed to be one of the two great gold pools of the gold-exchange standard in 1925–31. At the end of World War II, then, the Fed controlled the largest gold pool the world had ever seen. Fort Knox was the world’s gold pool even before the postwar system saw the light of day. The conference at Bretton Woods merely acknowledged this reality. The great majority of its delegates sought to create a postwar monetary order along the traditional lines—in which fractional-reserve central banks inflated their banknote currencies, backed up with gold reserves. This order was impossible without having the Fed as its pivot. But this meant that henceforth the monetary systems of France and Britain, and of all other member countries would be dependent on the Fed.[14]

To alleviate this dependency, the Bretton Woods conference created two international bureaucracies that have survived until the present day: the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank. The function of these institutions was to give the other major governments some impact on the global allocation of inflation. Without them, the Fed alone would have picked the first recipients of new banknotes; it alone would have granted or declined credit in times of runs on the national central bank. Through the IMF and the World Bank, a somewhat more collegial principle was introduced into the direction of the postwar monetary order. The boards of the two bureaucracies included representatives from all major western allies, and they provided short-term (IMF) and long-term (World Bank) loans to “member states in difficulties”—that is, primarily to the board members themselves in case of self-inflicted emergencies.

These institutions made the Bretton Woods system politically acceptable to the postwar junior partners of the United States government. But they could not of course turn the system itself into a viable operation. Like its predecessors, it was designed to increase the inflationary potential for all cartel members. Restraint was not a part of its mission, and the very anchor of the system—the Fed—was particularly ruthless in its inflation of the dollar supply. It was therefore just a question of time until the gold reserves of the Fed would be exhausted, forcing the Fed to suspend payments. This point was reached on August 15, 1971 when U.S. President Nixon “closed the gold window.”

The event concluded a period of one hundred years in which three great cartels of central banks had flooded the western world with their banknotes without nominally abandoning the gold standard. Each new cartel was created in such a way as to allow for more inflation than its predecessor, and the Bretton Woods cartel eventually collapsed because it too did not create enough inflation to satisfy the appetites of its members. There has been no other monetary system since that encompassed the entire world.

4. Appendix: The IMF and the World Bank After Bretton Woods

With the demise of the system of Bretton Woods, it would have been only natural to abolish its institutions: the IMF and the World Bank. But large bureaucracies do not die a quick death, especially if they can manage to adopt a new mission. By the late 1970s, the new mission of those two bureaucracies turned out to be the support of Third World countries through short-term and long-term loans.

Thus the IMF and the World Bank do not have anything to do anymore with global monetary organization. And strictly speaking they do not have anything to do anymore with banking either, at least if we understand banking in the narrow commercial meaning of the word. Both institutions are today, in actual fact, large machines for the mere redistribution of income from the taxpaying citizens of the developed countries to irresponsible governments of undeveloped countries.[15]

Many people let themselves be deluded about the IMF and the World Bank because they tend to evaluate financial institutions in light of their (declared) intentions rather than in light of their true nature. They assimilate the IMF into some sort of collective charity, and chide it for not being generous enough whenever the management insists on granting additional credit only under certain conditions (usually a change of economic policy in the recipient country). But the fact is that both bureaucracies do not obtain their funds on the free market, but out of government budgets. They spend taxpayer money, not money that anybody has entrusted to them. They are therefore not “banks,” certainly not in the commercial sense of the word. And they are not charities in the sense in which private organizations administer charity.

Responsible governments can obtain loans on the free market, and in fact do obtain such loans all the time. Poverty of the nation is not an obstacle, as many examples show, especially from Southeast Asia. It is true that certain governments are unable to find creditors—in particular those that do not pay back loans, or that nationalize foreign investments, or that regulate or tax investors to such an extent that profitable production becomes impossible. Such governments can only obtain “political credit” through intergovernmental organizations such as the IMF and the World Bank. Irresponsible governments make life in their countries miserable. As long as they have the backing of the citizens, they can stay in power. But in most cases they have this backing only as long as they can hand out material benefits, which they themselves obtain through taxation and expropriation. As soon as there is nothing more for them to loot, the population turns against them. This is where the political credit facilities of the IMF and the World Bank come into play. Their effect is to keep corrupt and irresponsible governments in business longer than they otherwise would be. Bokassa, Mobutu, Nkruma, Somoza and other dictators would not have stayed in power as long as they did without the financial support of those institutions.[16] The political price to be paid for these political loans usually consists in cooperative behavior in other fields, for example, when it comes to the establishment of Western military bases in these countries, or to international trade agreements, or to special privileges for a few large “multinational” corporations.

The Catholic Church has avidly endorsed the integration of all countries into the international division of labor, as a condition for economic and social development.[17] But leaders from the Third World have only very recently begun to demand the abolition of the protectionism that is so pervasive in the developed countries. Could it be that the effect of political credit was to mute for a long time any opposition to Northern protectionism in the underdeveloped South?

Free trade and private property are not some sort of legal privilege to the sole benefit of a small number of “haves” and to the exclusion of the great majority of have-nots. The case is exactly the reverse, as many economists have demonstrated: the have-nots stand to benefit most from a social order based on the undiluted respect of property rights. Governments that systematically expropriate investors and oppose free trade— be it out of ignorance or malice—ruin their citizens, and especially the poor. Organizations that support such governments create misery and death. It follows that political-credit organizations such as the World Bank and the IMF are needless at best—because responsible government would obtain credit anyway—and positively harmful in their actual operation. Support for them is hard to square with concern for the well-being of the poor.

See Herbert Rittmann, Deutsche Geldgeschichte seit 1914 (Munich: Klinkhardt & Biermann, 1986), chap. 1; Bernd Sprenger, Das Geld der Deutschen (Paderborn: Schöningh, 1995), chap. 10. ↩︎

The Latin Currency Union had been created in 1865 by the governments of France, Italy, Switzerland, and Belgium. Later members included Greece and Romania. The idea of the Union was to establish a common coin system for all member countries. It lasted, nominally, until 1926. In fact, it was abandoned in 1914 with the near-universal suspension of payments. ↩︎

See Leland B. Yeager, International Monetary Relations (New York: Harper & Row, 1966), pp. 252–58; Barry Eichengreen, Globalizing Capital, 2nd ed. (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1998), chap. 2, especially the section on the introduction of the international gold standard. ↩︎

The only exception was India, which adopted the gold standard in 1898. Russia made the step in 1897. China alone among the major countries remained on a silver standard. ↩︎

We have emphasized in the present work that there is nothing wrong with falling prices per se, and the period under consideration is in fact the best illustration of this claim. Growth rates were very substantial in the countries struck by the deflation. The point is that the fiat deflation brought forced hardship for those who would have fared better under a competitive regime that tolerated other types of specie than gold. ↩︎

See Guilo Gallarotti, The Anatomy of an International Monetary Regime: the Classical Gold Standard, 1880–1914 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995), pp. 78–85. ↩︎

See for example Yeager, International Monetary Relations, pp. 260–65; Henry Hazlitt, The Inflation Crisis, and How to Resolve It (Irvington-on-Hudson, N.Y.: Foundation for Economic Education, [1978] 1995), pp. 173f.; Rothbard, A History of Money and Banking in the United States (Auburn, Ala.: Ludwig von Mises Institute, 2002), pp. 159–69. See also the references in Barry Eichengreen, Globalizing Capital (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press), chap. 2. ↩︎

On the gold-exchange standard see Yeager, International Monetary Relations, pp. 277–90; Murray N. Rothbard, “The Gold-Exchange Standard in the Interwar Years,” Kevin Dowd and Richard H. Timberlak, eds., Money and the Nation State (New Brunswick, N.J.: Transaction, 1998), pp. 105–65. ↩︎

This practice was widespread even before the notes of the Bank of England became legal tender in 1833, mainly due to the introduction of a monopoly status for gold after 1821. ↩︎

See the overview in Eichengreen, Globalizing Capital, chap. 2, section on phases of the gold standard. ↩︎

Governments agreed on this principle at the Genoa Conference, held from April 10 to May 19, 1922. See Rothbard, “The Gold-Exchange Standard in the Interwar Years,” p. 130; Carole Fink, The Genoa Conference: European Diplomacy, 1921–1922 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1984). ↩︎

One of the few countries that abstained from participation in this system was France. The main motivation was to avoid political dependency on the Anglo-Saxon countries. The Banque de France had herself for a long time pursued the policy of dependence-creation vis-à-vis foreign banks. ↩︎

On the Bretton Woods system see in particular Jacques Rueff, The Monetary Sin of the West (New York: Macmillan, 1972); Henry Hazlitt, From Bretton Woods to World Inflation (Chicago: Regnery, 1984); Eichengreen, Globalizing Capital, chap. 4; Leland Yeager, “From Gold to the Ecu: The International Monetary System in Retrospect,” Kevin Dowd and Richard H. Timberlake, eds., Money and the Nation State (New Brunswick, N.J.: Transaction, 1998), pp. 88–92. ↩︎

This was one of the reasons why the government of the United Kingdom—under the leadership of Lord Keynes—pushed for a radically different postwar constitution at the Bretton Woods conference. Rather than pushing for more fractional-reserve banking, it proposed the establishment of a fiat paper money for the entire world. It expected to have greater influence on the allocation of the world paper money than it could hope to have on the allocation of U.S. dollars. ↩︎

See Roland Vaubel, “The Political Economy of the International Monetary Fund,” R. Vaubel and T.D. Willets, eds., The Political Economy of International Organizations: A Public Choice Approach (Boulder, Colo.: Westview Press, 1991), pp. 204–44; Alan Walters, Do We Need the IMF and the World Bank? (London: Institute of Economic Affairs, 1994); Jörg Guido Hülsmann, “Pourquoi le FMI nuit-il aux Africains?” Labyrinthe 16 (Autumn 2003). ↩︎

See George Ayittey, Africa in Chaos (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1998), pp. 270ff., where the author discusses the cases of Zambia, Rwanda, Somalia, Algeria, and Mozambique. ↩︎

See in particular the Second Vatican Council on Gaudium et Spes (1965); John Paul II, Sollicitudo Rei Socialis (1988); idem, Centesimus Annus (1991). Paul VI’s Populorum Progression (1967), which dealt with development economics, focused on the more problematic aspects of international trade. ↩︎