Chapter 15

Fiat Monetary Systems in the Realm of the Nation-State

1. Toward National Paper-Money Producers: European Experiences

The paper-money systems that presently dominate the scene in all countries of the world have developed out of European fractional-reserve banking starting in the seventeenth century. The driving force behind this development was government finance which found in the new institutions a ready source for ever-increasing loans.[1]

The most venerable central bank—or rather: paper money producer—of our time, the Bank of England, was established in 1694 by William Patterson, a Scottish promoter, with the express purpose of providing what was at the time the immense loan of £1,200,000 to the English crown.[2] Its charter authorized the bank to issue notes within certain statutory limitations, which were subsequently extended to allow for additional loans to the government. The bank was also granted several legal privileges, most notably the privilege of limited liability and the privilege of unilaterally suspending payments to its creditors, which the Bank had to use after a mere two years of operations. Apart from this early incident, however, the bank proved to be reliable and operated without suspending its payments in peacetime. In the following two hundred years, it thrived under the increasing patronage of the government, providing a steady flow of new loans without disrupting the convertibility of its notes.

In the early nineteenth century, Bank of England notes became legal tender, with the consequences that we described in our theoretical analysis: cartelization of the banking system and frequently recurring booms and busts. In 1844, it obtained a monopoly on the issue of banknotes.[3] And in 1914, at the behest of the king, the bank again suspended its payments, to help finance World War I with the printing press.

In other countries such as France and Germany, the development of the national monetary system took somewhat different turns, but the main elements of the British case can be readily identified: monopoly status for one precious metal (gold); privileged fractional-reserve banks in the service of government finance; legal-tender status for the notes of these banks; the consequent cartelization of the entire national banking industry; and the eventual authorization to indefinitely suspend redemption of the notes of the privileged bank, thus turning the latter into national paper-money producers.

In the case of the Bank of England, the conjunction of these elements was brought about by a rather slow process. By contrast, the privileged banks established in other countries were often quite reckless and inflated their currencies at much greater rates than the Bank of England, to still the financial appetite of their governments. Not surprisingly, they had to rely much more frequently on the suspension of payments and often experimented with legal-tender paper money. At the end of the eighteenth century, therefore, fractional-reserve banking and paper money had made great inroads in many countries. John Wheatley, a contemporary observer, summarized the events of the preceding century:

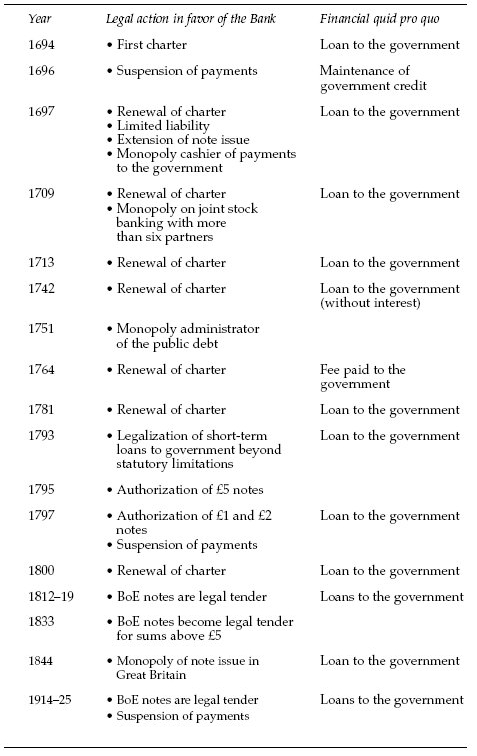

Table 2: Milestones in the Development of the Bank of England

During the first fifty years of the 18th century banks were established, or had already been founded in most of the principal cities of Europe, and the circulation of paper was more or less encouraged by all. …But the circulation of paper during this interval was intermissive and irregular; though pushed to an extreme in England and Scotland during the reign of William and part of the reign of Anne, and in France during the regency of the Duke of Orleans, yet its excess was in neither instance of long duration. …But from 1750 to 1800 the system of paper currency, however unpropitious in its commencement, was matured and perfected in every part of the civilized world. In England, Scotland, and Ireland, in France, Spain, Portugal, Italy, Austria, Prussia, Denmark, Sweden, and Russia, in America, and even in our Indian provinces, the new medium has been successfully established, and has subjected the intercourse of the world, in all its inferior as well as superior relations, to be carried on in a far greater degree by the intervention of paper than the intervention of specie.[4]

A few pages later, Wheatley characterized the relative market shares of banknotes and specie in the major European countries as of his writing:

In England, Scotland, and Ireland, in Denmark, and in Austria, scarcely any thing but paper is visible. In Spain, Portugal, Prussia, Sweden, and European Russia, paper has a decisive superiority. And in France, Italy, and Turkey only, the prevalence of specie is apparent.[5]

This was the situation in 1807. In the following decades, the trend continued. For example, Austria, Russia, and Italy had legal-tender paper monies for many decades in the nineteenth century. These note issues were limited in amount and did not have a full monopoly status; they circulated parallel with coins and banknotes. Eventually, most European countries suspended payments at the onset of Wold War I. From 1914 to 1925, for the first time ever in history, all major nations except for the U.S. used paper monies.

2. Toward National Paper-Money Producers: American Experiences

In the history of the North American colonies of the British Empire, the essential features of the European monetary experience can be found as well. But there are two particularities: the American champions of paper money had a more direct approach than their European cousins; and the American opponents of paper money triumphed, at least for a while, more thoroughly than any of their European friends ever would.[6]

In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the governments of the British colonies more often than not pushed straight for the issue of legal-tender paper notes rather than choosing the more indirect route of promoting privileged fractional-reserve banks. As early as 1690, the colony of Massachusetts issued paper treasury bills that were endowed with legal-tender status. This practice was replicated in five other colonies before 1711, and eventually spread to all British colonies. Among its victims were the creditors of American trade and industry, usually merchants from metropolitan Britain, who were forced to accept the often rapidly depreciating paper notes. They brought their case before Parliament which reacted vigorously starting in the 1720s. It first ordered all New England colonies to seek authorization from Britain before issuing any more legal-tender notes. In 1751, it prohibited the issue of any such notes in New England, and in 1764 prohibited the issue of any legal-tender paper in all colonies. This must have been a heavy blow to the political establishment in the British colonies of North America. It is certainly not farfetched here to see one of the roots of the American Revolution.

However, the Revolution did not bring a legal confirmation of the monetary experiments of the colonial period. Quite to the contrary, the American Constitution is, in the modern history of the West, the most radical legal break with a country’s inflationary past. The fathers of the new republic did all in their power to prevent legal-tender paper issues of the colonies (now the states) ever to be repeated again. They moreover strove to create a monetary order based on the precious metals. These objectives were deemed so important that they were addressed head-on in the very first article of the Constitution. Section 8 of Article I granted the authority to “coin Money, regulate the Value thereof, and of foreign Coin, and fix the Standard of Weights and Measures” to the federal government, not to the states. And Section 10 of Article I specifically prohibited that the states “emit Bills of Credit; make any Thing but gold and silver Coin a Tender in Payment of Debts.”

The Constitution proved to be a serious obstacle for the party of inflation, but it ultimately was breached. For the next sixty years, the battle between pro-inflation and anti-inflation forces went back and forth. The champions of inflation pushed through the charters of two “Banks of the United States” (1792–1812, 1816–1836) and their opponents made sure that the charters were not extended. In the war of 1812–14, the federal government issued legal-tender treasury notes—necessary, in the eyes of the government, for the survival of the new republic (and of course for its own survival). In the 1830s, then, the champions of sound money had their last great triumph when President Jackson refused to extend the charter of the Second Bank of the United States, withdrew all public funds from private or state (fractional-reserve) banks, and cut down the public debt from some 60 million at the beginning of his administration to a mere 33,733.05 on January 1, 1835. His successors managed to neutralize these reforms to some extent, especially by bringing the public debt back to more than $60 million within fifteen years of the end of the second Jackson administration.

But the great breakthrough for the inflation party came only with Abraham Lincoln and the War Between the States. Starting in 1862, the federal government again issued a legal-tender paper money, the so-called greenbacks, to finance its war against the seceding Southern states. This experiment ended in 1875, when the government turned the greenbacks into credit money, by announcing that as from 1879 they would be redeemed into gold.[7] Meanwhile, in 1863–65, the Lincoln administration had created a new system of privileged “national banks” that were authorized to issue notes backed by federal government debt, while the notes of all other banks were penalized by a 10 percent federal tax. As a consequence American banking was centralized around the privileged national banks, most notably, the reserve banks of New York City.

In 1913, then, the American banking system finally received a central bank on the European model. The U.S. was the last great nation to introduce central banking. The original interpretation of the Constitution had prevented a quicker procedure for more than a century, but the written word was unable to stem the tide of concentrated financial interests and their pro-inflation public relations campaigns.

The point of the preceding remarks on the early modern monetary history of the West is to highlight the long tradition of our current inflationary regime. It is not the case that monetary affairs were rosy until 1914, when the great inflation of the twentieth century set in. It is true that in our time inflation is incomparably greater than in any previous period, especially due to the current monopoly of paper money. But the roots of our present calamities are much older. This concerns not only the institutional underpinnings, which reach back to the seventeenth century. It also concerns the concrete forms of inflation. Neither paper money, nor today’s other major inflationary practices are inventions of the twentieth century. And even the much-vaunted gold standard, which reigned for a few decades before World War I, was not quite as golden as it appears in many narratives.

3. The Problem of the Foreign Exchanges

While national legislation prompted the cartelization of the fractional-reserve banking industry within the boundaries of the nation, no such mechanism existed for a long time in international economic relations. Thus until after World War I, the bulk of international payments were made in specie. But in the four or five decades before the outbreak of that war, the foundations were laid for the later establishment of international monetary systems.

All of these systems until the present day have been essentially cartels among national governments, respectively between national monetary authorities (usually the central banks). Two phases can be distinguished: (1) a phase of banking cartels, which lasted for the century between the end of the Franco-German war in 1871 and the dissolution of the Bretton Woods system in 1971; and (2) a phase of cartels among national paper-money producers, which started in 1971 and is still with us. The next two chapters will deal with them in turn. At this point, let us merely observe that none of these cartels has so far been compulsory. It remains to be seen whether the future development of international political relations will bring about any changes.

For an overview see Vera Smith, The Rationale of Central Banking (Indianapolis: Liberty Fund, 1990), chaps. 1 to 6; Norbert Olszak, Histoire des banques centrales (Paris: Presses Universitaires de France, 1998). ↩︎

On the history of the Bank of England see John H. Clapham, The Bank of England: A History, 1694–1914 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, [1944] 1970). ↩︎

Other note-issuing banks that already existed in 1844 were allowed to continue their business within their statutory limitations. Most of them eventually decided to switch the business model and became checking banks. ↩︎

Wheatley, The Theory of Money and Principles of Commerce (London: Bulmer, 1807), pp. 279–80. Wheatley’s statement on the “intercourse of the world” concerns especially international wholesale trade. Things were often quite different in daily retail transactions. On the case of the German lands, see Bernd Sprenger, Das Geld der Deutschen, 2nd ed. (Paderborn: Schöningh, 1995), pp. 153–54. ↩︎

Wheatley, The Theory of Money and Principles of Commerce, p. 287. ↩︎

On the history of American money and banking until the early twentieth century see William Gouge, A Short History of Paper Money and Banking in the United States (reprint, New York: Augustus M. Kelley, [1833] 1968), part II; William G. Sumner, History of Banking in the United States (New York: Augustus M. Kelley, [1896] 1971); Barton Hepburn, History of Coinage and Currency in the United States and the Perennial Contest for Sound Money (London: Macmillan, 1903); Bray Hammond, Banks and Politics in America (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1957); Donald Kemmerer and Clyde Jones, American Economic History (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1959); Murray N. Rothbard, A History of Money and Banking in the United States (Auburn, Ala.: Ludwig von Mises Institute, 2002). ↩︎

At this point, the U.S. Supreme Court had first ruled against the legality of legal-tender privileges for paper (1870) and then revised its decision in subsequent cases (1871 and 1874). See Donald Kemmerer and C. Clyde Jones, American Economic History (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1959), p. 356. ↩︎