Chapter 12

Paper Money

1. The Origins and Nature of Paper Money

The foregoing discussion has prepared us to deal with the most important case of fiat inflation, namely, with the production of paper money. We have already mentioned that paper money never spontaneously emerged on the free market. It was always a pet child of the government and protected by special legal privileges. We have moreover pointed out the typical sequence of events through which it is established: In a first step, the government establishes a monopoly specie system, either directly by outlawing the monetary use of the other precious metals, or indirectly through the imposition of a bimetallist system. Then it grants a monopoly legal-tender status to the notes of a privileged fractional-reserve bank. Finally, when the privileged notes have driven the other remaining means of exchange out of the market, the government allows its pet bank to decline the (contractually agreed-upon) redemption of these notes. This suspension of payments then turns the former banknotes into paper money.

This scheme fits the sequence of events in all major western countries. Fractional-reserve banknotes had emerged in the seventeenth century and experienced exponential growth rates during the eighteenth century, invariably as a form of government finance and sustained by various privileges. During the nineteenth century, the issues of several privileged banks—the later central banks—acquired monopoly legal-tender status, while the monetary use of silver was outlawed either directly (Germany, France) or indirectly through bimetallist systems (England, U.S.). To finance the unheard-of destructions of World War I, then, the central banks of France, Germany, and Great Britain suspended the redemption of their notes. Needless to say, this happened with the approval and in fact at the behest of their national governments. Only the Fed did not suspend its payments in World War I, and only the Fed redeemed its notes after World War II under the so-called Bretton Woods system, which lasted until the redemption of U.S. dollar notes was suspended in 1971 (other central banks resumed the redemption of their notes into gold in 1925–31). Since 1971, the entire world is “off the gold standard”—all countries use fiat paper monies.

It is certainly possible to imagine other feasible ways through which paper money could be introduced, but these shall not concern us here. Our point is that, as a matter of fact, paper monies have been introduced in each single case through various progressive infringements on private property, and through massive breaches of contract perpetrated by the central banks. These facts are certainly relevant for a moral evaluation of paper money. In light of them, paper money appears to be tainted by more than a fair share of original sin.

But then there is also another consideration, even more crucial for a proper economic and moral assessment of paper money. The fundamental fact is that, even now, every single paper money continues to exist only because of special legal privilege, which shields it from the competition of other paper monies as well as from the natural monies gold and silver. In particular, paper money is still legal tender and it still enjoys a monopoly on payments that have to be made to governments.[1] This leads us to the important conclusion that paper money is by its very nature a form of (fiat) inflation. It exists only because of continued legal privileges.[2] It is always and everywhere in greater supply than it would be on the free market, for the simple reason that on the market it could not sustain itself at all.

This is the only sense in which paper money can be considered to be a form of inflation. We have to emphasize this point because much ambiguity has been introduced into the debate by a number of opponents of paper money, who have criticized it with the argument that producing paper money was a form of counterfeiting.[3] But this is not the case. A monetary authority that produces its own paper money does not engage in counterfeiting. It does not claim to do or to represent anything other than what it does and represents.

It could be argued that the current notes of the Bank of England provide a counterexample. These banknotes not only feature a portrait of Queen Elizabeth, but also the imprint “I promise to pay the bearer on demand the sum of £20” (on £20 notes). Is this not a fraudulent promise? Is it not a case of counterfeiting? It is not. In actual fact the promise to pay £20 is not more than a deferential bow before the British mind, which worships the preservation of forms that have long outlived their former content. Until 1914, and then between 1925 and 1931, the Bank of England redeemed its £20 notes into a quantity of gold that was called “the sum of £20.” Today it redeems these notes into other notes of the same kind. The point is that in the old days the expression “the sum of £20” had a different legal meaning than it has today. At the time it designated some five ounces of gold.[4] Today it means something different. The suspension of payments has turned the expression “the sum of £20” into a self-referential tautology— it now designates £20 paper notes. The notes that promise payment of “the sum of £20” do no more than promise payment in like notes. This sheds of course a somewhat unflattering light on the Queen of England, who appears to make empty promises. But it is an oddity, not a lie.

2. Reverse Transubstantiations

We need to extend the foregoing consideration somewhat further. It is indeed a characteristic problem of paper money that it combines traditional forms with a radically new content.

The suspension of payments that turns banknotes into paper money entails various “reverse transubstantiations”—an expression we use because the phenomenon at issue bears a certain resemblance with the central liturgical event of the Catholic mass. We have to speak of a reverse transubstantiation, however, because the transubstantiation that results from human hands in the economic sphere cannot be said to sanctify things or otherwise improve them in any sense.[5]

Suppose there is a central bank that issues legal-tender banknotes, and that its notes have a wide circulation. One day the government authorizes the bank to suspend redemption forever. The notes continue to enjoy legal-tender privileges, and the bank declares that it has no intention whatever to resume redemption at any point in the future. This transforms the former banknotes into paper money and the former central bank into a paper money producer. The former banknotes and the former bank preserve all of their external characteristics—the notes still look and smell and feel exactly as before, the buildings of the former bank still displays the inscription “Bank,” and so on—but their natures have changed. The notes are no longer certificates.[6] They just are what they are: legal tender paper slips. And the former bank is no longer a bank even though it might still call itself “XY Bank” or “Bank of Ruritania.” A bank deals with money—it offers financial intermediation, safeguarding of deposits, issuing money certificates, and so on. Some banks actually fake money certificates—fractional-reserve banks. But no bank in the proper meaning of the word ever makes money. By contrast, the producer of irredeemable legal-tender notes does make money. He is not a banker, but a money producer, in quite the same sense in which gold miners or silver miners are money producers on the free market.

Thus we see in which sense reverse transubstantiation occurs through legal acts that authorize the suspension of payments of legal-tender notes. Such acts leave all physical appearances intact; but they change the essence of the notes and of the issuer of these notes.

Our present-day world is a paper-money world. On August 15, 1971, the central bank of the world, the U.S. Federal Reserve System, suspended the redemption of its notes; and there is presently no intention whatever to ever resume their redemption into specie. The legal act that authorized the suspension of August 1971 transformed the U.S. dollar into a paper money, and by the same token it transformed the banknotes issued by all other central banks into paper money too. It is true that we still call our paper money “banknotes,” that we call the Fed a “Bank,” that the Bank of Japan has preserved its name, and that a new “bank” of the same type has been established, namely, the European Central Bank. But as a matter of fact our present day paper-money notes are no longer banknotes, and the aforementioned “banks” are not banks.[7]We stress these facts in some detail because the entire matter poses great difficulties even to experienced observers, and is one of the most widespread sources of confusion for students of monetary affairs. Of course we cannot explore at this point the interesting philosophical questions related to the phenomenon of reverse transubstantiation. We need to focus on the practical implications of paper-money production.

3. The Limits of Paper Money

One important aspect of this new reality is that institutions like the Fed cannot go bankrupt. They can print any amount of money that they might need for themselves at virtually zero cost. Consider that it takes just a drop of ink to add one or two zeros to a $100 bill! Here is the great difference between the production of paper money and the production of natural monies such as gold and silver. Miners can go bankrupt. They cannot increase their production ad libitum, because profitable gold and silver production is possible only within fairly narrow limits. As we have just seen, no such limits exist for the production of paper money.[8]

What imposes certain constraints on paper-money producers is not the danger of bankruptcy, but the danger of hyperinflation. If the purchasing power of their notes declines at such a rapid pace that it becomes ruinous to hold them in one’s purse for any length of time, then the citizens would at some point rather forgo the benefits of monetary exchange altogether than go on using these notes. That point is usually reached when the notes lose the bulk of their purchasing power by the hour—a typical phenomenon in the terminal phase of historical hyperinflations. People then stop using the currency (“flight from money”) and the economy disintegrates, especially if the government does not lift the legal-tender privilege or adopt some other emergency measure, for example, an all-round monetary reform.[9]

Hyperinflation is a rather loose limitation. In the last thirty years, national and international paper monies have been produced in extraordinary quantities, surpassing any inflationary experience of the past that did not produce a collapse. But although some minor currencies have collapsed in hyperinflations, none of the major currencies (dollar, yen, and euro) has thus far shared this fate.

4. Moral Hazard and Public Debts

The most visible consequence of the global paper-money inflation of the past thirty years is the explosion of public debt. To be true, the debts of private individuals and organizations have increased as well, and this was also as a consequence of inflation. But their growth has been insignificant compared to the growth of public debt.

Consider the situation of a private debtor. The amount of money he can borrow from other people is essentially limited by his present assets and by his expected revenue. He simply could not pay back any sum exceeding this limit. (From the economic point of view, any money “lent” to him in excess of this limit would not be a credit at all, but some form of assistance.) Private debts therefore by and large tend to grow under inflation to the extent that the growing monetary revenues warrant ever higher credits. But however strong the inflation may be, the amount of private credit granted is still limited by present assets and expected revenue.

Now contrast this state of affairs with the situation of a government. The amount of money it can borrow also depends on its present resources and expected revenue from taxation. However, its potential monetary resources are unlimited because it enjoys unlimited credit from its central bank, the national paper money producer. Central banks are public institutions with special loyalties and obligations toward their governments. As we have seen, they cannot go bankrupt, because they can create ex nihilo any amount of money without any technical or economic limitation. It follows that governments too cannot go bankrupt as long as they have the full loyalty of their central banks. Moreover, they can obtain credit far in excess of their current assets and expected revenue from taxation. Investors know that the paper money producer stands behind its government. They therefore know that government will always be able to meet any financial obligation that is denominated in the money of its central bank. As a consequence investors will be willing to buy ever more government bonds even if there is no hope that the public debt could ever be repaid out of tax revenue.

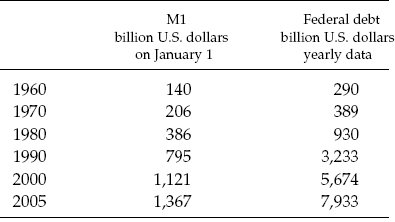

As a tendency, therefore, public debt under a paper-money system does not simply grow at the same pace as the money supply, but at a much faster rhythm. For example, in the case of the U.S., since 1971 the money supply has been increased by the factor 6, whereas the federal debt has grown by the factor 20 (see Table 1).

Those who entertain doubts about the loyalty of today’s central banks toward their governments should consider that the leadership of these institutions consists entirely of political appointees and that their much-vaunted “independence” can be abrogated by simple majorities in parliament.

Table 1: Evolution of M1 and Public Debt in the U.S.

One might object that the central banks do not in fact have the legal authorization to replenish the public purse with the printing press. But this objection misses the mark even though it is correct in a narrow technical sense. To be sure, the central banks may generally not engage in any direct manner to refinance their governments. However, they cannot be prevented from doing this in a more roundabout way, with the help of their partners in the banking sector and the financial markets. As a matter of fact, central banks increase the money supply mainly through the purchase of short-term financial titles (this is called “open-market policy”). No law prevents—or could conceivably prevent—that such purchases be tied up with an explicit or implicit obligation for the seller to give new credits to the government. In current practice it is not even necessary to impose any such obligation. Banks and investment funds are very eager buyers of government bonds.

5. Moral Hazard, Hyperinflation, and Regulation

Many economists have speculated about the feasibility of pure paper-money systems. Some argue that paper-money producers could fabricate money of better quality—more stable purchasing power—than the traditional monies, gold and silver. And they add that this would happen if paper-money producers were forced to operate on a free market.

All such considerations are intellectual moonshine. The idea of stable paper money is at odds with all historical experience. And the theoretical case for that idea has no better foundation. We have already pointed out that the ideal of a stable purchasing power is a chimera, and that there are good reasons to believe that no paper money could sustain itself in a truly free competition with gold and silver. Now let us bring a further consideration into play. It is indeed very doubtful that paper-money producers, even if they thoroughly wished to stabilize the purchasing power of their product, could prevent a general economic crisis. The reason is, again, that the mere possibility of inflating the money supply creates moral hazard.

The production of gold and silver does not depend on the good will of miners and minters; and the users of gold and silver coins, as well as creditors and debtors, know this. Therefore they do not speculate on the sudden availability of additional gold and silver supplies that miraculously emerge from the depths of the mines. They make all kinds of other errors in their speculations, but not this one. Under a paper-money standard, by contrast, people do speculate on the good will of paper-money producers; and they do not do this in vain. Such speculation occurs on a large scale, because people know that paper money can be produced in virtually any quantity. It is really just a matter of good will on the side of the producers. It follows that more or less all market participants will tend to be more reckless in their speculations than they otherwise would have been—a sure recipe for wasteful use of resources and possibly also for macroeconomic collapse.

If just a few persons speculate on the assistance of the paper-money producer, they can be helped with the printing press at the expense of all other owners of money. Suppose that the money supply of an economy is three billion thalers. If one entrepreneur goes bankrupt and is helped by his friends from the central bank with three million thalers fresh from the printing press, the impact on prices might hardly be noticeable. But now suppose one thousand entrepreneurs do the same thing. The owner of the printing press then faces a hard choice. Either he helps them too, but in this case he would have to double the money supply, which could hardly fail to have dramatic negative repercussions. Or he declines the requests for assistance; then it would come to mass bankruptcy.[10]

The second alternative is of course not really an option. Political pressure on the paper-money producer to comply with the requests would be so great that he could hardly resist this pressure and hope for the continuation of peaceful business relations with the government and others. It is naïve to believe that he could impress people with his case for stable money while their businesses collapse en masse. And apart from that, the second alternative also carries great commercial risks for him. Large-scale bankruptcy is usually incompatible with a stable price level, and it is likely to reduce the exchange rate vis-à-vis other currencies.

But assume that the producer of the paper money announces with a stern voice and steely eyes that he will be steadfast in his determination to never ever (“read my lips”) issue more notes than necessary for the stabilization of purchasing power. Would this be quite as convincing as the implicit guarantees of a gold or silver standard? The answer is patent. Hence, the inescapable dilemma of a paper-money producer is that his mere presence creates moral hazard on the side of all other market participants. This in turn will make it impossible for him to avoid increasing rates of inflation in the long run, with the ultimate prospect of a runaway hyperinflation.

The West is still at the beginning of its great experiment with paper money—thirty years is not a long time for a monetary institution. But already the foregoing considerations find a ready confirmation in the economic statistics of the past thirty years, which witnessed an exponential growth of the money supply, as well as of debts private and public, in all major western countries.

Evidence for moral hazard on a mass scale could be found in the last ten years or so in the stock-exchange mania, as well as in the real-estate boom in the United Kingdom and the U.S. Here the market participants have invariably displayed the same characteristic behavior. They have evaluated the assets without regard for the price-earnings ratio, speculating entirely on finding, at some point in the future, a buyer who is even more bullish than they are now, and who will therefore consent to pay an even higher price.

Consider the current (2006) U.S. real-estate boom. Many Americans are utterly convinced that American real estate is the one sure bet in economic life. No matter what happens on the stock market or in other strata of the economy, real estate will rise. They believe themselves to have found a bonanza, and the historical figures confirm this. Of course this belief is an illusion, but the characteristic feature of a boom is precisely that people throw any critical considerations overboard. They do not realize that their money producer—the Fed—has possibly already entered the early stages of hyperinflation, and that the only reason why this has been largely invisible was that most of the new money has been exported outside of the U.S.[11] Money prices have increased tremendously above the level they would have reached without the relentless production of greenbacks, but the absolute increase of the domestic price level (as measured by CPI figures) has been relatively moderate so far. However, as soon as foreigners slow down their purchases of U.S. dollars domestic prices will start soaring, and then hyperinflation looms around the corner.

In the past, governments have tried to counter this trend through regulations. Moral hazard first became visible in the banking industry, and today this industry is indeed very strongly regulated.[12] The banks must keep certain minimum amounts of equity and reserves, they must observe a great number of rules in granting credit, their executives must have certain qualifications, and so on. Yet these stipulations trim the branches without attacking the root. They seek to curb certain known excesses that spring from moral hazard, but they do not eradicate moral hazard itself. As we have seen, moral hazard is implied in the very existence of paper money. Because a paper-money producer can bail out virtually anybody, the citizens become reckless in their speculations; they count on him to bail them out, especially when many other people do the same thing. To fight such behavior effectively, one must abolish paper money. Regulations merely drive the reckless behavior into new channels.

One might advocate the pragmatic stance of fighting moral hazard on an ad-hoc basis wherever it shows up. Thus one would regulate one industry after another, until the entire economy is caught up in a web of micro-regulations. This would of course provide some sort of order, but it would be the order of a cemetery. Nobody could make any (potentially reckless!) investment decisions anymore. Everything would have to follow rules set up by the legislature. In short, the only way to fight moral hazard without destroying its source, fiat inflation, is to subject the economy to a Soviet-style central plan.

Central planning or hyperinflation (or some mix between the two)—this is what the future holds for an economy under paper money. The only third way is to abolish paper money altogether and to return to a sound monetary order.

6. The Ethics of Paper Money

We need not dwell much on the ethics of paper money. In the light of our foregoing discussion, the case should be clear. Notice first of all that a good moral case against paper money can be made on the mere ground of its illegitimate origins. Paper money has never been introduced through voluntary cooperation. In all known cases it has been introduced through coercion and compulsion, sometimes with the threat of the death penalty.

And as we have seen, there are good reasons to believe that paper money by its very nature involves the violation of property rights through monopoly and legal-tender privileges. But at any rate it is a matter of fact that, at present, all paper monies of the world continue to be protected through such legal privileges in their countries of origin. We have argued that these privileges cannot be justified, certainly not in the case of money, because there is no need for fiat inflation. It follows that our present-day paper monies, which thrive on these privileges, are morally inadmissible.

The production of paper money has posed formidable obstacles to appropriate ethical judgement. The opponents of paper money among the economists usually claim that the production of paper money is inflation—as though the distinction between money production and inflation could be made along purely physical lines. But this view is problematic because it comes close to condemning the production of money per se. The relevant fact about our present-day paper monies is not that they are paper monies, but that they are fiat paper monies. Their continued production could possibly be justified, even though they have been introduced by illegitimate means. But their imposition by law cannot be justified, as we have argued in some detail.

One of the few weaknesses in Ludwig von Mises’s theory of money concerns this point. Mises states: “It can hardly be contested that fiat money in the strict sense of the word is theoretically conceivable. The theory of value proves the possibility of its existence” (Theory of Money and Credit, [Indianapolis: Liberty Fund, 1980], p. 75, see also p. 125). Notice that the expression “fiat money” in Mises’s book is a translation of the original expression “Zeichengeld” which translates literally as “sign money.” In fact, the essence of fiat money according to Mises is special legal earmarking to facilitate evaluation by money users. It has nothing to do with the invasion of the property rights of these money users. Fiat money “comprises things with a special legal qualification” (ibid., p. 74). All that the government does here is “to single out certain pieces of metal or paper from all the other things of the same kind so that they can be subjected to a process of valuation independent of that of the rest” (ibid.). In the light of the fact that Mises was wrong on this issue, it is certainly excusable that other writers have let themselves be drawn into certain excesses that derive from that same error. A case in point is Michael Novak, who celebrates the nonmaterial character of modern paper monies in his Spirit of Democratic Capitalism (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1982), pp. 348–49. But to really make this point, one would have to prove (1) that the use of gold and silver coins inherently precludes moral and spiritual virtues, and (2) that the lack of a “material” dimension in paper money is inherently praiseworthy from a moral and spiritual point of view. No such proof has been delivered, and it is safe to predict that it will never be delivered. As we have argued, the case is exactly the reverse of what Novak and others assume. The very materiality of gold, silver, and other precious metals makes them especially suitable as money in free society; whereas it is the very nonmateriality of paper money that requires constant coercion to keep them in circulation. ↩︎

The point has apparently been stressed already in the nineteenth century by the German legal scholar Thöl. See Karl Heinrich Rau, Grundsätze der Volkswirtschaftslehre, 7th ed. (Leipzig & Heidelberg, 1863), §295, annotation (d), p. 373. ↩︎

See in particular Murray N. Rothbard, The Mystery of Banking (New York: Richardson & Snyder, 1983), pp. 51–52 and passim; Gary North, Honest Money (Ft. Worth, Texas: Dominion Press, 1986), chap. 9; Thomas Woods, The Church and the Market (Lanham, Md.: Lexington Books, 2005), p. 97; Friedrich Beutter, Zur sittlichen Beurteilung von Inflationen (Freiburg: Herder, 1965), pp. 157, 173. Beutter also qualifies inflation as theft; see ibid., 91, 154. ↩︎

1 ounce of gold was defined as 3 pounds, 17 shillings, 10.5 pence, or £3.89. ↩︎

I owe the expression “reverse transubstantiation” to Professor Jeffrey Herbener. For a number of years, I have used in classroom the expression “economic transubstantiation.” But this is a euphemism. ↩︎

The imprints on coins and banknotes no longer certify ownership of a certain amount of precious metal. Rather, they certify the legitimate origin of these coins and banknotes. Also, present-day coins are no longer certificates; they are not even token money as they were in previous times. ↩︎

More precisely, we would have to say that the nature of present-day “banknotes” is different from the nature of pre-suspension banknotes; and that the nature of present-day central banks is different from the nature these institutions had before the suspension. ↩︎

A few years ago, the present chairman of the U.S. central bank emphasized this possibility, and the willingness of the authorities to make use of it, if need be, to dispel deflation fears. He said:

↩︎Like gold, U.S. dollars have value only to the extent that they are strictly limited in supply. But the U.S. government has a technology, called a printing press (or, today, its electronic equivalent), that allows it to produce as many U.S. dollars as it wishes at essentially no cost. By increasing the number of U.S. dollars in circulation, or even by credibly threatening to do so, the U.S. government can also reduce the value of a dollar in terms of goods and services, which is equivalent to raising the prices in dollars of those goods and services. We conclude that, under a paper-money system, a determined government can always generate higher spending and hence positive inflation. (Ben Bernanke, “Deflation: Making Sure ‘It’ Doesn’t Happen Here” [Remarks before the National Economists Club, Washington, D.C., 21 November 2002])

Notice again that all historical hyperinflations have been inflations of paper money. See Peter Bernholz, Monetary Regimes and Inflation (Cheltenham, U.K.: Edward Elgar, 2003). ↩︎

We can neglect at this point all considerations about the intertemporal misallocation of resources that such mass speculation might entail. See Jörg Guido Hülsmann, “Toward a General Theory of Error Cycles,” Quarterly Journal of Austrian Economics 1, no. 4 (1998). ↩︎

According to the Federal Reserve Board, between 1995 and 2005 the Fed increased its note issues at an annual pace of 6.6 percent (compare: under a gold standard, annual production has hardly ever added more than 2 percent to the existing gold stock). The Board estimates that between one-half and two-thirds of all U.S. dollar notes are held abroad. See http://www.federalreserve.gov/paymentsystems/coin/default.htm (update of March 14, 2006). ↩︎

The same thing holds true for financial markets and labor markets. Other markets that are also strongly affected by moral hazard springing from paper money have so far escaped heavy regulation. Notable cases in point are real estate markets. ↩︎