Protecting Privacy with Electronic Cash

[Originally published in Extropy #10 Winter/Spring (vol. 4, no. 2)]

How can we defend our privacy in an era of increased computerization? Today, our lives are subject to monitoring in a host of different ways. Every credit card transaction goes into a database. Our phone calls are logged by the phone company and used for its own marketing purposes. Our checks are photocopied and archived by the banks. And new “matching” techniques combine information from multiple databases, revealing even more detail about our lives. As computer databases grow, as more transactions take place electronically, over phone systems and computer networks, the possible forms of monitoring will grow with them.[1]

Predictably, most proposed solutions to this problem involve more government. One suggestion is to pass a set of laws designed to restrict information usage: “No information shall be used for a purpose different from that for which it was originally collected.” Thus, income data collected by a bank through monitoring checking account activity could not be made available to mailing list companies; phone records could not be sold to telemarketing agencies, etc.

But this is a bad solution, for many reasons. The government is notoriously inefficient at enforcing existing laws, and the ease of collecting and using information suggests that it would be almost impossible to successfully enforce a law like this. The government also has a tendency to exempt itself from its own laws. It’s unlikely that the IRS, for example, will happily give up the use of database matching, which it uses to track down tax evaders. And, of course, the very notion of trying to restrict the uses of information requires strict restrictions on the private actions of individuals which Extropians will find unacceptable.

But there is another solution, one advocated forcefully by computer scientist David Chaum of the Center for Mathematics and Computer Science in the Netherlands. While most people concerned with this problem have looked to paternalistic government solutions, Chaum has been quietly putting together the technical basis for a new way of organizing our financial and personal information. Rather than relying on new laws and more government, Chaum looks to technical solutions. And these solutions rely on the ancient science devoted to keeping information confidential: cryptography.

Cryptography, the art of secret writing, has undergone a revolution in the last two decades, a revolution sparked by the invention of “public-key” cryptography. Seizing on this new technology, computer scientists have branched out into dozens of directions, pushing the frontiers of secrecy and confidentiality into new territory. And it is these new applications for cryptography which offer such promise for avoiding the dangers described above.

Chaum’s approach to the protection of privacy can be thought of as having three layers. The first layer is public-key cryptography, which protects the privacy of individual messages. The second layer is anonymous messaging, which allows people to communicate via electronic mail (“email”) without revealing their true identities. And the third layer is electronic money, which allows people to not only communicate but to transact business via a computer network, with the same kind of privacy you get when you use cash. If you go into a store today and make a purchase with cash, no records are left tying you personally to the transaction. With no records, there is nothing to go into a computer database. The goal of electronic cash is to allow these same kinds of private transactions to take place electronically.

(Be aware that there are other proposals for “electronic money” which are not nearly so protective of individuals’ privacy. Chaum’s proposals are intended to preserve the privacy attributes of cash, so the term “digital cash” is appropriate. But other electronic replacements for cash not only lack its privacy, but would actually facilitate computer monitoring by putting more detailed information into databases, and by discouraging the use of cash. If you see a proposal for an electronic money system, check to see whether it has the ability to preserve the privacy of financial transactions the way paper money does today. If not, realize that the proposal is designed to harm, not help, individual privacy.)

Public-Key Cryptography

The first of the three layers in the privacy-protecting electronic money system is public-key cryptography. The basic concept of public-key cryptography, invented in 1976 by Diffie and Hellman,[2] is simple. Cryptographers have traditionally described an encryption system as being composed of two parts: an encryption method and a key. The encryption method is assumed to be publicly available, but the key is kept secret. If two people want to communicate, they agree on a secret key, and use that to encrypt and decrypt the message.

Public key cryptography introduced the idea that there could be two keys rather than one. One key, the public key, is known to everyone, and is used to encrypt messages. The other key, the secret key, is known only to you, and is used to decrypt messages. Public and secret keys are created in pairs, with each public key corresponding to one secret key, and vice versa.

So, to use a public-key system, you first create a public/secret key pair. You tell all your friends your public key, while keeping your secret key secret. When they want to send to you, they encrypt the message using your public key. The resulting encrypted message is readable only by using your secret key. This means that even the person who encrypted the message can’t decrypt it! If he forgets what his original message said, and he deleted it, he has no chance of reconstructing the original. Only you can do that. This is the paradox of public-key cryptography—that a person can transform a message in such a way that they can’t un-transform it, even though they know the exact formula used to make the transformation.

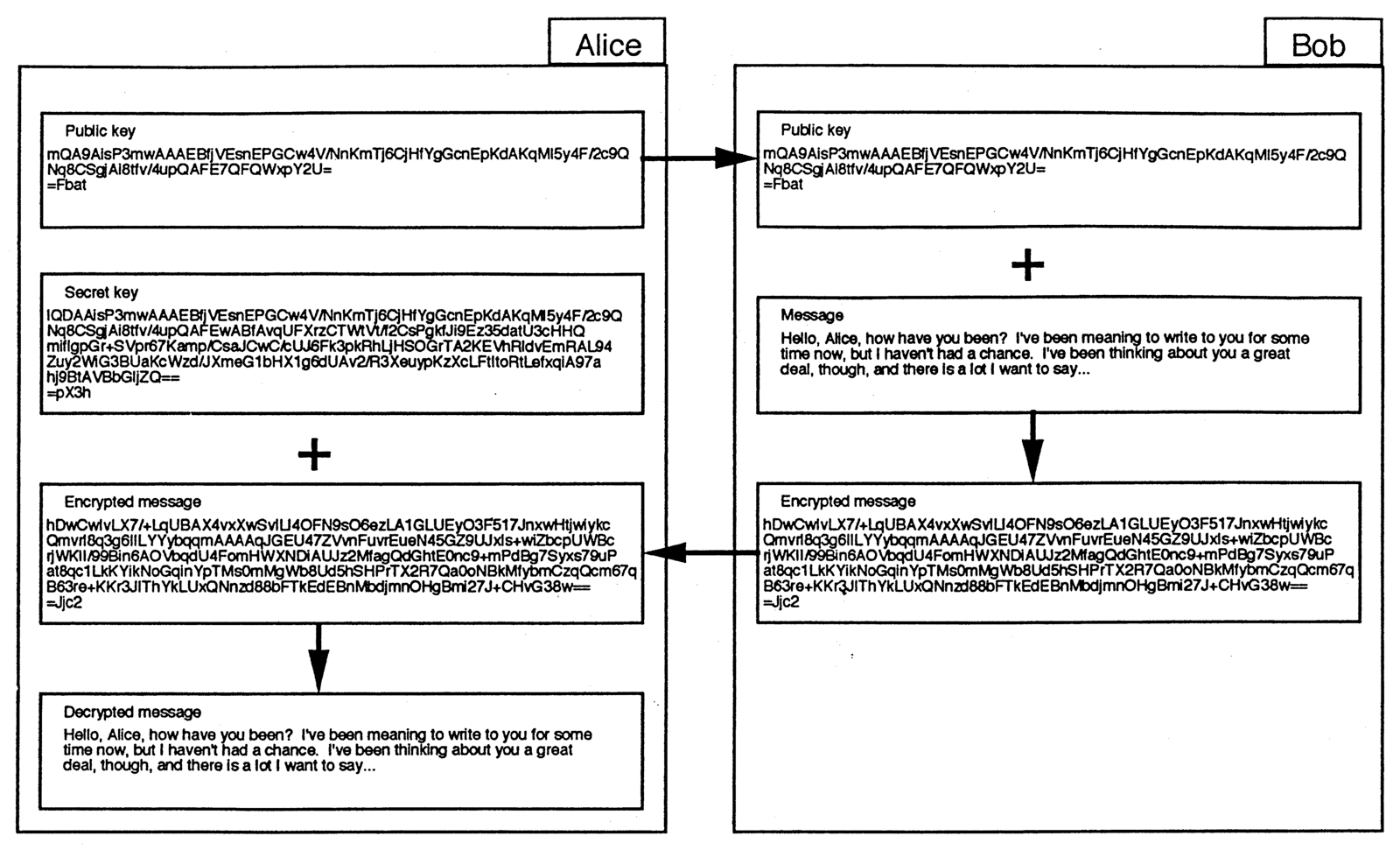

Figure 1 illustrates the steps involved in using a public-key system. (The keys and messages are based on actual output from Phillip Zimmermann’s free public-key program, PGP.) Alice, on the left, first creates a public and secret key pair, the top two boxes on that side. The top box, the public key, she sends to her friend Bob, on the right. The second box is her secret key, which she keeps private. Bob, on the right, receives and saves Alice’s public key. Then, when he wants to write to her, he composes a message, shown in the second box on that side. With a public-key encryption program like PGP, he encrypts the message using Alice’s public key, producing output such as the third box on the left. This encrypted message is what he sends to Alice, as shown in the third box leading back to the left side. Alice uses her saved secret key to decrypt the message from Bob, allowing her to reconstruct Bob’s original message, as shown as the last box on the left side.

There is no longer any need for public-key cryptography to be mysterious. There are now public-domain software packages which make it easy to experiment with public-key cryptography on your own computer, including Zimmermann’s PGP and others. See the “Access” box for information on how to get them.

Anonymous Messages

Public-key cryptography allows people to communicate electronically with privacy and security. You can send messages safe from prying eyes using these techniques. But this is just a step towards the solution to the privacy problems we face. The next step provides the second layer of privacy: anonymous messages—messages whose source and destination can’t be traced.

This is necessary because of the goal of providing in an electronic network the privacy of an ordinary cash transaction. Just as a merchant will accept cash from a customer without demanding proof of identity, we also want our electronic money system to allow similar transactions to take place, without the identity of the people involved being revealed to each other, or even to someone who is monitoring the network.

There are problems with providing anonymous messaging in current email systems. The national email networks are composed of thousands of machines, interconnected through a variety of gateways and message-passing systems. The fundamental necessity for a message to be delivered in such a system is that it be addressed appropriately. Typically an email address consists of a user’s name, and the name of the computer system which is his electronic “home”. As the message works its way through the network, routing information is added to it, to keep a record of where the message came from and what machines it passed through en route to its destination. In this system, all messages are prominently stamped with their source and destination. Providing anonymous messages in such a system at first appears impossible.

Chaum has proposed two separate systems for overcoming this problem.[3] I will focus here on what he calls a “Mix” as it is simpler and more appropriate for the application of anonymous electronic mail. The notion of a Mix is simple. It is basically a message forwarding service. An analogy with ordinary paper mail may be helpful. Imagine that you want to send a letter to a friend, but in such a way that even someone monitoring your outgoing mail would not know that you were doing this. One solution would be to put your letter into an envelope addressed to your friend, then to place this envelope inside a larger envelope which you would send to someone else, along with a note asking them to forward the letter to your friend. This would hide the true destination of your mail from someone who was watching your outgoing envelopes.

Chaum’s Mixes use this basic idea, but applied to email and improved with public-key cryptography. A Mix is a computer program capable of receiving email. It receives messages which contain requests for remailing to another address, and basically just strips off these remailing instructions and forwards the messages as requested. Chaum adds security by having a different public key for each Mix. Now, instead of just sending the message with its forwarding request, the message plus forwarding info is encrypted with the Mix’s public key before being sent to the Mix. The Mix simply decrypts the incoming message with its secret key, revealing the forwarding information, and sends the message on.

To protect the privacy of the sender, the Mix removes information about the original sender of the message before sending it. For even greater security, it’s possible for the original sender to specify a “Cascade” of Mixes, a whole chain of Mixes that the message should go through before finally being sent to its destination. That way even if one of the Mixes is corrupt, it still can’t determine who is sending to whom.

Using Mixes, then, the basic requirement for anonymous mail is met. A message en route in the network does not have to reveal its source and destination. It may be coming from a Mix, going to a Mix, or some combination of these.

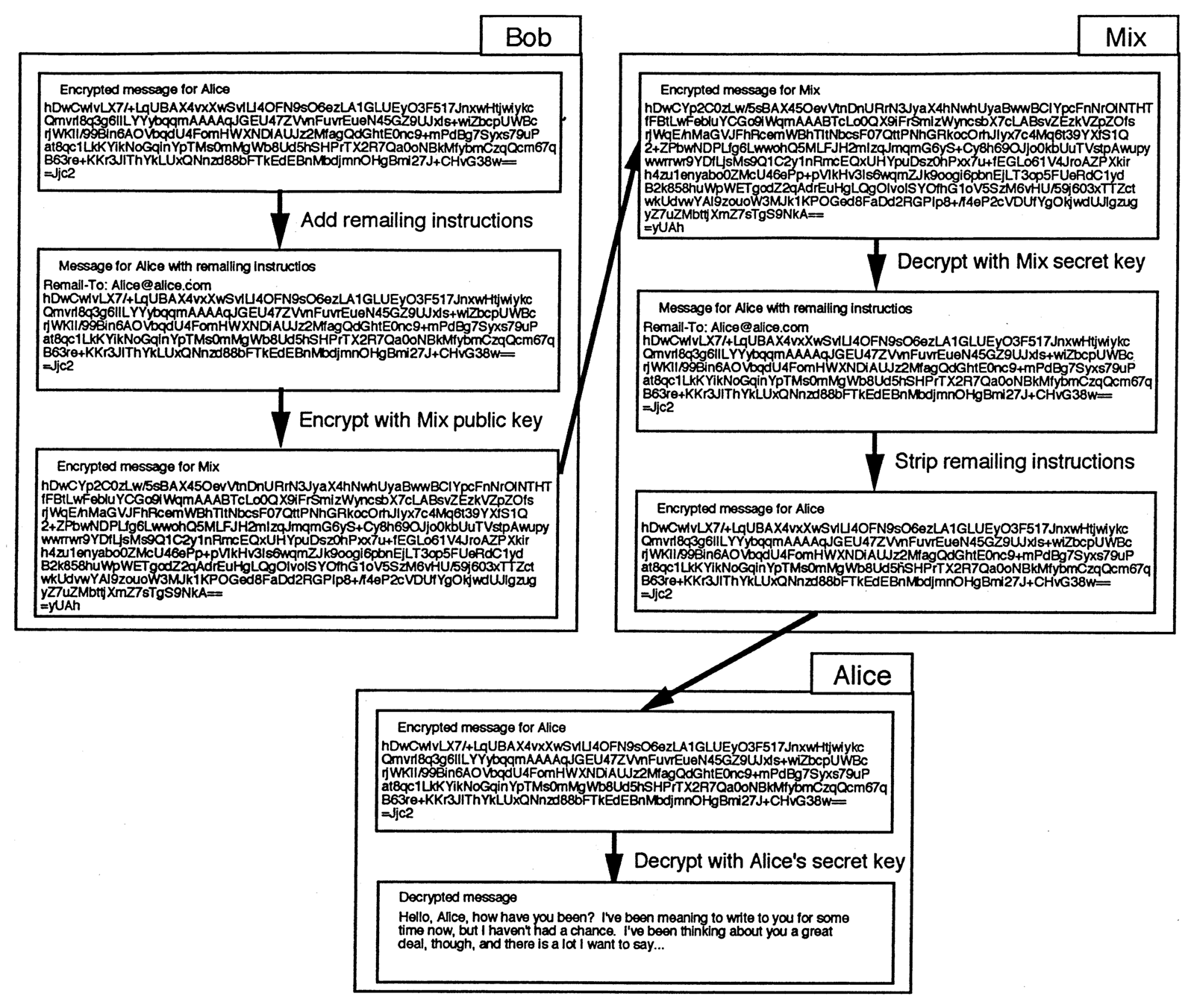

Figure 2 shows an example of an anonymous message as it is forwarded through a Mix, using public-key cryptography to protect its privacy. As in Figure 1, Bob wants to send his encrypted message to Alice, but this time he wants to use a Mix to provide more confidentiality. Starting with the encrypted message from Figure 1, Bob (on the left, this time) first adds remailing instructions which will be interpreted by the Mix. These will include Alice’s email address in some format specified by the Mix. (This example uses a simplified form of commands currently being used in experimental remailers.) Then he encrypts the whole message with the Mix’s public key and sends it to the Mix.

Upon receipt, the Mix reverses the steps which Bob applied. It decrypts the message using its own secret key, then strips off the remailing instructions which Bob added. The resulting message (which the Mix can’t read, being encrypted using Alice’s secret key) is then forwarded to Alice as specified in the remailing instructions. As before, Alice receives and decrypts the message using her secret key. But this time, the message path has been protected by the Mix, and the fact that Alice and Bob are communicating is kept confidential.

Anonymous Return Addresses

We need something more advanced than message anonymity for truly private messaging, though. These anonymous messages are basically “one-way”. I can send you a message, with the source and destination hidden, and when you receive the message you won’t have any way of knowing who sent it. This means that you can’t reply to me. We need the ability to have such replies.

Here, we have a seemingly paradoxical requirement: being able to reply to someone without knowing either who they are or what their email address is. Chaum shows how this can be solved using public-key cryptography and Mixes. The basic idea is what Chaum calls an Anonymous Return Address (ARA). In its simplest form, I create an ARA by taking my regular email address and encrypting it with the public key of a particular Mix—call it MixA for this example. I send this resulting block of encrypted text along with my message to you, through a Cascade of Mixes.

Now, when you receive the message, you see no return address, but you do see the block of text that is the ARA. You can reply to me without knowing who I am by sending your reply back to MixA, along with the ARA itself. MixA decrypts the ARA using its secret key, getting back my original email address that I encrypted. Using this email address, it is able to forward the mail to me. I was able to receive this message from you, although you have no knowledge of my true identity.

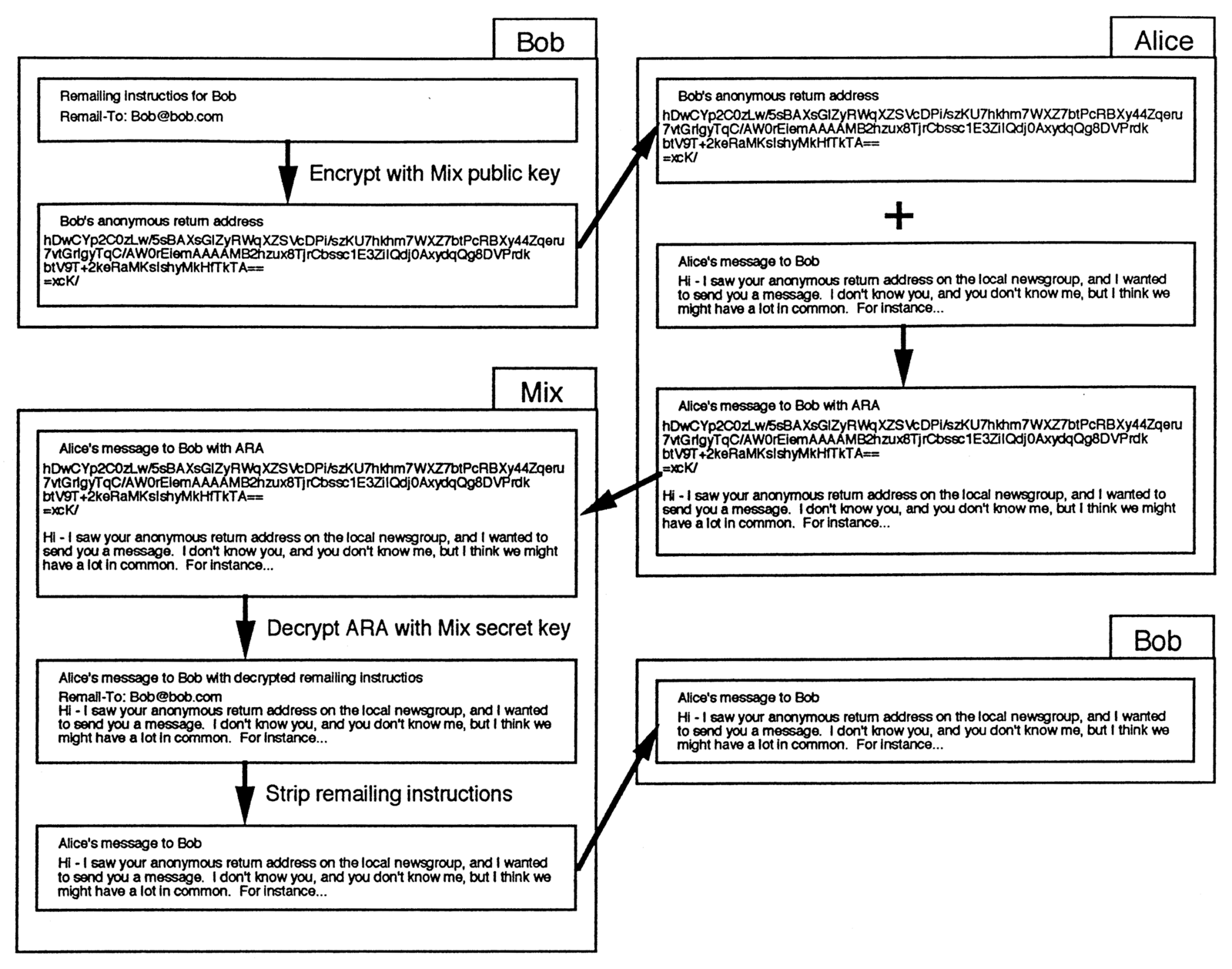

Figure 3 shows this process graphically. Bob, in the upper left, creates his ARA by encrypting a remailing command, similar to what was used in Figure 2, with the Mix’s public key. He then includes this ARA in messages which he anonymously sends or publicly posts. In the example, Alice sees Bob’s ARA and wishes to respond to him, even though she doesn’t know his email address. She composes her message, in the second box on the right, then combines her message with Bob’s ARA. The combined message is sent to the Mix. The Mix now uses its secret key to decrypt the ARA portion of the message, revealing the remailing instructions which Bob encrypted to create the ARA. The remainder of the process is just as in Figure 3. The Mix strips off the remailing request and forwards the message to Bob’s address, as shown.

These tools open many possibilities. With Mixes, Cascades, and ARAs, people can communicate without knowing other people’s true identities. You can make an anonymous posting to a public message board, include your ARA, and receive replies from scores of people who don’t know who you are. Some of them may reply anonymously and include their own ARAs. People can end up communicating with each other with none of them knowing the true identity of any of the others.

(Some “Chat” or “CB Simulator” systems today offer the illusion of such anonymous communication, but in most cases the system operators can easily break through the cover of handles and pseudonyms and discover true identities. With a Cascade of Mixes, no single Mix can establish this relationship. As long as even one Mix of the Cascade remains uncorrupted, your identity is safe.)

Digital Pseudonyms

Anonymous messages bring the usefulness of “digital pseudonyms,” another concept from Chaum. With no identification of the source of messages, there would seem to be no way of verifying that two messages came from the same person. There could be a problem with imposters pretending to be other people, resulting in utter confusion. To solve this problem, we need another concept from public-key cryptography: the “digital signature.”

As described above, public-key cryptography allows messages encrypted with my public key to be decrypted with my secret key. However, it works the other way around as well. Messages can be encrypted with my secret key and then decrypted only with my public key. This property is what is used to implement the digital signature. If I encrypt a document with my secret key, anyone can decrypt it with my public key. And since my secret key is secret, only I can do this type of encryption. That means that if a document can be decrypted with my public key, then I, and only I, must have encrypted it with my secret key. This is considered a digital signature, in the sense that it is a proof that I was the one who “signed” (that is, encrypted) the document.

The digital signature concept can also be used to solve the imposter problem by allowing for “digital pseudonyms.” My digital pseudonym is simply a public/secret key pair, where, as usual, I let the public part be known. Typically, I’d publicize it along with my ARA. Now, to prove that a given message is from me and no one else, I sign the message using the secret key of my digital pseudonym. Any set of messages signed by that same digital pseudonym is therefore known to come from me, because only I know the secret key. People may not know who I am, but I can still maintain a stable public persona on the computer nets via my digital pseudonym. And there is no danger of anyone else successfully masquerading as me.

With public-key cryptography, Mixes, and digital pseudonyms, we have all we need for a network of people communicating privately and anonymously. Now, we need a way for them to transact business while maintaining these conditions.

Electronic Money

The next step, the third layer in our description, is digital cash—electronic money. Cash, ordinary folding paper money, is one of the last bastions of privacy in our financial lives. And many of the problems described above—the losses of privacy, the increase in computerized information—could be avoided if cash could be used more easily. But cash has many disadvantages. It can be lost, or stolen, and it’s not safe to carry in large quantities. Also, it is useless for purchases made electronically, over the phone or (in the future) over computer networks. Digital cash is designed to combine the advantages of electronic payment systems—the safety and the convenience—with the advantages of paper money—the privacy and anonymity.

Once again, we are faced with paradoxes in the notion of digital cash. Since digital cash may be sent by email and other electronic methods, it must basically be an information pattern—in concrete terms, some pattern of letters and numbers. How could such a string of characters have value, in the same sense that the dollar bill in your wallet does? What about counterfeiting? Couldn’t another copy of the character string be created trivially? What prevents a person from “spending” the same money twice?

To answer these questions we turn again to public-key cryptography. Realize, though, that electronic money is an active area of research in cryptography. Many people have proposed different systems for electronic cash, each of which has its own advantages and disadvantages. I will present here a simplified concept to give a feel for the problems and solutions which exist.[4]

One way to think of digital cash is by analogy to the early days of paper money. At one time, paper money was not the monopoly of governments that it is today. Instead, paper money was “bank notes”, often given as receipts for the deposit of gold or similar “real money” in bank vaults. These notes would carry a description of what they were worth, such as, “Redeemable for one ounce of gold.” A particular bank note could be redeemed at the issuing bank for its face value. People used these bank notes as we use paper money today. They were valuable because they were backed by materials of value in the bank vaults.

In a sense, then, a bank note can be viewed as a signed document, a promise to perform a redemption for the bearer who presents it at the bank. This suggests a way of thinking of digital money. Instead of a paper note with an engraved signature, we instead would use an electronic mail message with a digital signature.

An electronic bank could, like the banks of old, have valuable materials in its vaults. Today, these would likely be dollars or other government currency, but they could be gold or other commodities. Using these as backing, it would issue bank notes. These would be electronic messages, digitally signed by the bank’s secret key, promising to transfer a specified sum to the account of whomever presented the note to the bank (or, if desired, to redeem the note in dollars or other valuables).

Here is how it might work. You open an account with an electronic bank, depositing some money as in any bank. The bank then credits your account with your initial balance. Now, suppose you are going to want to make an electronic payment to me. Prior to any transactions, you would send a message to the bank, requesting one or more bank notes in specified denominations. (This is exactly analogous to withdrawing cash from your regular bank account.) The bank debits your account, creates new bank note messages, and sends them to you. They are sent to you as signed messages, encrypted with the bank’s secret key. When decrypted with the bank’s public key, which everyone knows, a one-dollar digital bank note would say, in effect, “This note is worth $1.00, payable on demand.” It would also include a unique serial number, like the serial number on a dollar bill.

The serial number is important; as we’ll see below, it is used by the bank to make sure that a particular note is accepted for deposit only once. But putting serial numbers on the bank notes hurts anonymity; the bank can remember which account a bank note was withdrawn from, and then when it is deposited the bank will know that the depositor is doing business with the withdrawer. To avoid this, Chaum introduces a clever mathematical trick (too complex to describe here) which allows the serial number to be randomly changed as the note is withdrawn from the bank. The bank note still retains its proper form and value, but the serial number is different from the one the bank saw. This allows the bank to check that the same note isn’t deposited more than once, while making it impossible for the bank to determine who withdrew any note that is deposited.

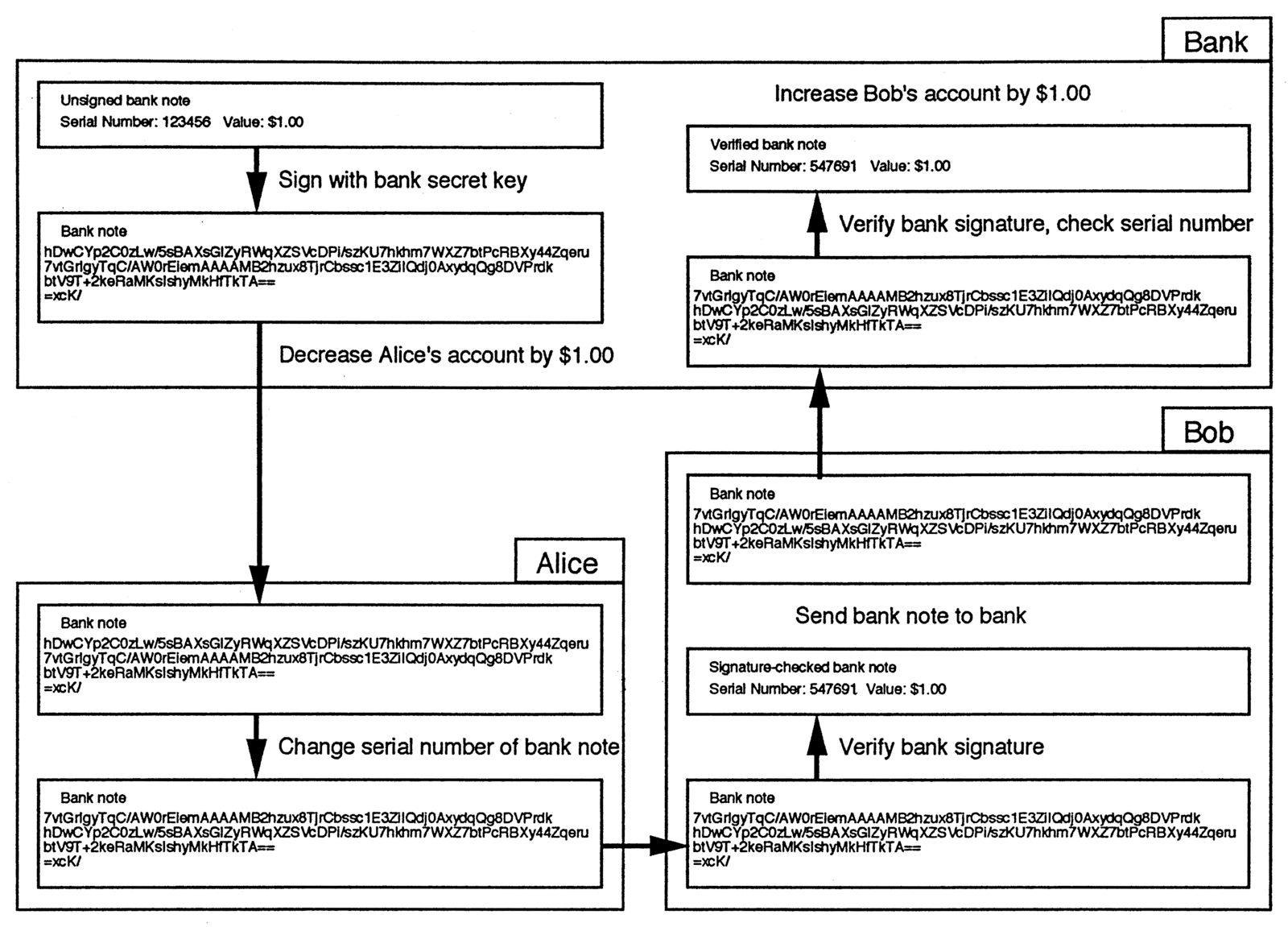

When you are ready to purchase something from me, you simply email me the appropriate bank note messages. I can check that they are legitimate bank notes by using the bank’s public key to verify its signature. I then email the notes to the bank, which checks that the account numbers on the notes have not been deposited before this. If they are valid bank notes, the bank credits my account for the face value of the notes. Your account was decreased when you withdrew the bank notes, which you held like cash, and mine was increased when I sent them to the bank. The result is similar to how it would work if you withdrew (paper) cash from the bank, mailed it to me, and I deposited the cash in my own account.

Figure 4 shows a similar transaction between Alice and Bob. The bank, in the upper left corner, creates a digital bank note by signing a message which specifies the serial number and value of the note, and sends it to Alice. Alice, as she withdraws it, uses Chaum’s technique to alter the serial number so that the bank will not recognize the note as being from this withdrawal. She then pays Bob electronically by sending the bank note to him. Bob checks the note’s validity by decrypting using the bank’s public key to check its signature. He then sends the note to the bank, which checks the serial number to confirm that this bank note hasn’t been spent before. The serial number is different from that in Alice’s withdrawal, preventing the bank from linking the two transactions.

With this simple picture in mind, we can begin to answer some of the objections listed above. Bank notes cannot be forged because only the bank knows the secret key that is used to issue them. Other people will therefore not be able to create bank notes of their own. Also, anyone can check that a bank note is not a forgery by verifying the bank’s digital signature on the note. As for the copying issue, preventing a person from spending the same bank note more than once, this is handled by checking with the bank to see if the serial number on the note had been used before before accepting a bank note as payment. If it had been, the note would not be accepted. Any attempt to re-use a bank note will be detected because the serial number will be a duplicate of one used before. This means, too, that once you “spend” your digital cash by emailing it to someone, you should delete it from your computer, as it will be of no further value to you.

This simple scheme gives some of the flavor of electronic cash, but it still has awkward features. The need to check with the bank for each transaction may be inconvenient in many environments. And the fixed denominations of the bank notes described here, the inability to split them into smaller pieces, will also limit their usefulness. Chaum and others have proposed more complex systems which solve these problems in different ways.[5] With these more advanced systems, the anonymity, privacy, and convenience of cash transactions can be achieved even in a purely electronic environment.

Electronic Money in Practice

Having described the three layers of privacy protection, we can now see how electronic transactions can maintain individual privacy. Public-key cryptography protects the confidentiality of messages, as well as playing a key role in the other layers. Anonymous messaging further allows people to communicate without revealing more about themselves than they choose. And electronic money combines the anonymity of cash with the convenience of electronic payments. David Chaum has described variations of these techniques that can extend privacy protection to many other areas of our lives as well.[6]

Although my description of digital cash has been in terms of computer networks with email message transactions, it can be applied on a more local scale as well. With credit card sized computers, digital cash could just as easily be used to pay for groceries at the local supermarket as to order software from an anonymous supplier on the computer networks. “Smart card” computers using digital cash could replace credit or debit cards for many purposes. The same types of messages would be used, with the interaction being between your smart card and the merchant’s card reader.

On the nets themselves, any goods or services which are primarily information-based would be natural candidates for digital cash purchases. Today this might include things such as software, electronic magazines, even electronic books. In the future, with higher-bandwidth networks, it may be possible to purchase music and video recordings across the nets.

As another example, digital cash and anonymous remailers (such as Chaum’s Mixes) have a synergistic relationship; that is, each directly benefits the other. Without anonymous remailers, digital cash would be pointless, as the desired confidentiality would be lost with each transaction, with message source and destination blatantly displayed in the electronic mail messages. And in the other direction, digital cash can be used to support anonymous remailing services. There could be a wide range of Mix services available on the nets; some would be free, and presumably offer relatively simple services, but others would charge, and would offer more service or more expensive security precautions. Such for-profit remailers could be paid for by digital cash.

What are the prospects for the eventual implementation of digital cash systems and the other technologies described here? Some experiments are already beginning. David Chaum has started a company, DigiCash, based in Amsterdam, which is attempting to set up an electronic money system on a small scale. As with any new business concept, though, especially in the conservative financial community, it will take time before a new system like this is widely used.

The many laws and regulations covering the banking and financial services industries in most Western nations will undoubtedly slow the acceptance of digital cash. Some have predicted that the initial success of electronic money may be in the form of a technically illegal “black market” where crypto-hackers buy and sell information, using cryptography to protect against government crackdowns.

In the nearer term, the tools are in place now for people to begin experimenting with the other concepts discussed here. Public-key cryptography is becoming a reality on the computer networks. And experimental remailers with integrated public-key cryptosystems are already in use on a small scale. Digital-pseudonym-based anonymous message posting should begin happening within the next year. The field is moving rapidly, and privacy advocates around the world hurry to bring these systems into existence before governments and other larger institutions can react. See the “Access” box for information on how you can play a part in this quiet revolution.

We are on a path which, if nothing changes, will lead to a world with the potential for greater government power, intrusion, and control. We can change this if technologies can revolutionize the relationship between individuals and organizations, putting them both on an equal footing for the first time. Cryptography can make possible a world in which people have control over information about themselves, not because government has granted them that control, but because only they possess the cryptographic keys to reveal that information. This is the world we are working to create.

Notes

- For a review of the status of current monitoring technology, see [Clarke88]. ↩

- See [Diffie 76]. ↩

- The “Mix” is described in [Chaum 81]. Chaum’s other solution, the “DC-Net”, is described in [Chaum 88A]. ↩

- The electronic money scheme I describe is a simplification of Chaum’s first proposal in [Chaum 88B]. ↩

- For more proposals about electronic cash, see: [Even 83], [Chaum 85], [Okamoto 89], [Okamoto 90], [Hayes 90], and [Chaum 90]. ↩

- See [Chaum 85] and [Chaum 92]. ↩

References

[Chaum 81] Chaum, D., Untraceable Electronic Mail, Return Addresses and Digital Pseudonyms. Communications of the ACM, vol. 24, n. 2, p. 84-88, February, 1981.

[Chaum 85] Chaum, D., Security without Identification: Transaction Systems to make Big Brother Obsolete. Communications of the ACM, vol. 28, n. 10, p. 1030-1044, October, 1985.

[Chaum 88A] Chaum, D., The Dining Cryptographers Problem: Unconditional Sender and Recipient Untraceability. Journal of Cryptology, vol. 1, p. 65-75, 1988.

[Chaum 88B] Chaum, D., Fiat, A., Naor, M., Untraceable electronic cash. In: Advances in Cryptology - CRYPTO 88, p. 319-327, 1988.

[Chaum 90] Chaum, D., Showing Credentials without Identification: Transferring Signatures between Unconditionally Unlinkable Pseudonyms. In: Advances in Cryptology - AUSCRYPT ’90, p. 246-64, 1990.

[Chaum 92] Chaum, D., Achieving Electronic Privacy. Scientific American, vol. 267, n. 2, p. 96-101, August, 1992.

[Clarke 88] Clarke, R., Information Technology and Dataveillance. Communications of the ACM, vol. 31, n. 5, p. 498-512, May, 1988.

[Diffie 76] Diffie, W., Hellman, M., New Directions in Cryptography. IEEE Transactions on Information Theory, November, 1976, p. 644.

[Even 83] Even, S., Goldreich, O., Electronic Wallet. In: Advances in Cryptology - CRYPTO ’83, p. 383-386, 1983.

[Hayes 90] Hayes, B., Anonymous One-Time Signatures and Flexible Untraceable Electronic Cash. In: AusCrypt ’90, p. 294-305, 1990.

[Okamoto 89] Okamoto, T., Ohta, K., Disposable Zero-Knowledge Authenticators and Their Application to Untraceable Electronic Cash. In: Advances in Cryptology - CRYPTO ’89, p. 481-496, 1989.

[Okamoto 90] Okamoto, T., Ohta, K., Universal Electronic Cash. In: Advances in Cryptology - CRYPTO ’90, p. 324-337, 1990.

Access

Public-Key Cryptography

Phillip Zimmermann’s free program PGP (“Pretty Good Privacy”) is a widely available implementation of public key cryptography. It features high speed and has excellent key management, and operates on many systems, including PC compatibles, Macintoshes, and most Unix-based workstations. At publication time, version 2.1 was current. Readers with Internet access should be able to find PGP on such hosts as princeton.edu (/pub/pgp20) and pencil.cs.missouri.edu (/pub/crypt). Many of the larger bulletin-board systems carry PGP as well. Send email to Hugh Miller at <[email protected]> for current information, or check the Usenet newsgroup alt.security.pgp.

Mark Riordan’s free program RIPEM was in beta test at press time, with a release expected soon. Contact the author at <[email protected]> for information about availability.

The Internet PEM (“Privacy Enhanced Mail”) standard was due to be completed soon at press time. PEM uses a key-management hierarchy in which users register their public keys with a centralized organization. Free software implementing the basic public-key algorithms was expected to be available soon after the standard is finalized. Mail to <[email protected]> for more information on availability.

Anonymous Remailers

An email discussion group exists which is devoted to the topics of encryption, remailers, digital cash, and other topics related to these. Experimental anonymous remailers are under developement at press time and should be widely available soon. Contact <[email protected]> for information.