Chapter Five

Bitcoin Is the Great Definancialization

Originally published

on 23 December 2020 in The Bitcoin Times, Edition 3

Engineered Decay

Have you ever had a financial advisor, or maybe even a parent, tell you that you need to make your money grow? This idea has been so hardwired into the minds of hard-working people all over the world that it has become practically second nature to the very idea of work.

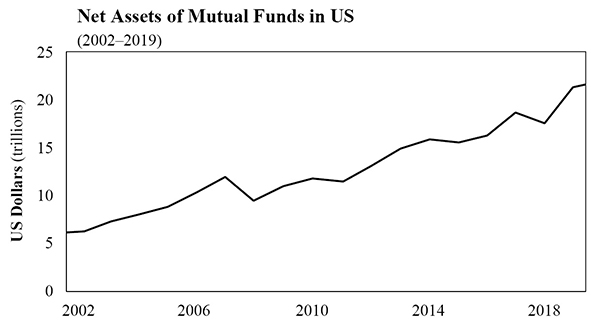

The line has been repeated so many times that it is now a de facto part of working culture. Get a salaried position, max out your 401(k) contribution (maybe your employer matches 3%!), select a few mutual funds with catchy marketing names, and watch your money grow. Most folks navigate this path on autopilot every two weeks, never questioning the wisdom nor being conscious of the risks. It is just what “smart people” do. Many now associate the activity with savings, but in reality, financialization has turned retirement savers into perpetual risk-takers. The consequence is that investing has become a second full-time job for many, if not most.

Financialization has been so errantly normalized that the lines between saving (not taking risk) and investing (taking risk) have become blurred to the extent that most people think of the two activities as being one and the same. Believing that financial engineering is a necessary path to a happy retirement might lack common sense, but it has become conventional wisdom.

Over the course of the last several decades, economies have become increasingly financialized, particularly in the developed world (and specifically the US). Increased financialization has become the necessary companion to the idea that you must make your money grow. But the idea itself only emerged in the mainstream consciousness as everyone similarly became conditioned to the unfortunate reality that money loses its value over time.

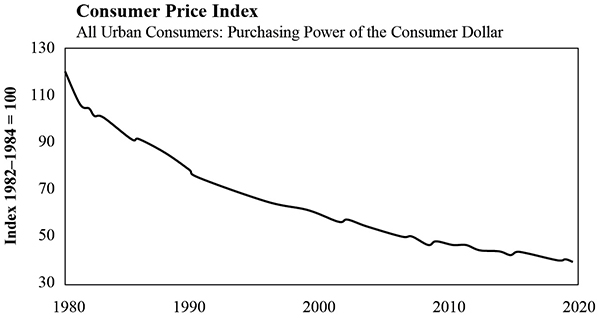

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics

Money Loses Value → Need to Make Money Grow → Need Financial Products to Make Money Grow → Repeat.

The extent to which the need even exists is largely a function of money losing its value over time. That is the starting point, and the most unfortunate part is that central banks intentionally engineer this outcome. Most global central banks target the devaluation of their local currencies by approximately 2% per year and do so by increasing the money supply. How or why is less relevant. It is a reality, and there are consequences. Rather than simply being able to save for a rainy day, future retirement funds are invested and put at constant risk, often just as a means to keep up with the very inflation manufactured by central banks.

Central banks perversely drive the demand function for such investments by devaluing money. An overfinancialized economy is the logical conclusion of monetary inflation, and it has induced perpetual risk-taking while disincentivizing savings. A system that disincentivizes saving and forces people into a position of risk-taking creates instability, and it is neither productive nor sustainable. It should be obvious to even the untrained eye that the overarching force driving the trend toward financialization, and financial engineering more broadly, is the broken incentive structure of the monetary medium that underpins all economic activity.

At a fundamental level, there is nothing inherently wrong with joint-stock companies, bond offerings, or any pooled investment vehicle for that matter. While individual investment vehicles may be structurally flawed, there can be (and often is) value created through pooled investment vehicles and capital allocation functions. Pooled risk is not the issue, nor is the existence of financial assets. Instead, the fundamental problem is the degree to which the economy has become financialized as an unintended consequence of otherwise rational responses to a broken and manipulated monetary structure.

What happens when hundreds of millions of market participants realize that their money is artificially, yet intentionally, engineered to lose 2% of its value every year? It is either accept the inevitable decay or try to keep up with inflation by taking incremental risk, and the overwhelming majority of people have been conditioned to the latter. The consequence is that money must be invested, meaning it must be put at risk of loss. Because monetary debasement never abates, this cycle persists. Essentially, people take risk in their day job and are then trained to put any money they do manage to save right back at risk, just to keep up with inflation, if nothing more. It is the definition of a hamster wheel—running hard just to stay in the same place. It may be absurd, but this is the present reality. And it is not without consequence.

Savings vs. Risk

While the relationship between savings and risk is often misunderstood, risk must be taken in order for any individual to accumulate savings in the first place. Risk comes in the form of dedicating time and energy to some pursuit that others value (and must continue to value) in order to be compensated (and continue to be compensated). It starts with education, training, and ultimately perfecting a craft over time that others value. That is risk-taking. Investing time and energy in an attempt to earn a living and to produce value for others requires accepting high degrees of future uncertainty. If successful, it ends with a classroom of students, a product on a shelf, a world-class performance, a full day of hard manual labor, or anything else that others value. The risk is taken on the front end with the hope and expectation that someone else will compensate you for your time spent and value delivered.

Compensation typically comes in the form of money because money, as an economic good, allows individuals to convert their own value into a wide range of value created by others. In a world in which money is not manipulated, monetary savings would best be described as the difference between the value one has produced for others and the value one has consumed from others. Savings is simply consumption or investment deferred into the future. Said another way, savings represents the excess of what one has produced but not yet consumed. That, however, is not the world that exists today. With modern money, there is a fly in the ointment.

Central banks create more and more money, which causes savings to be perpetually devalued. The entire incentive structure of money is manipulated, including the integrity of the scorecard that tracks who has created and consumed what value. Any value created today is ensured to purchase less in the future as central banks arbitrarily allocate more units of the currency. Money is intended to store value, not lose value. But with monetary economics engineered by central banks, everyone is unwittingly forced into the position of taking risk as a means to continuously replace savings as it is debased. Rather than benefiting from risks already taken, everyone is forced to take incremental risk.

Forcing risk-taking on practically all individuals within an economic system is not natural, nor is it fundamental to the functioning of an economy. It is precisely the opposite, and it is detrimental to the stability of the system as a whole. As an economic function, risk-taking itself is productive, necessary, and inevitable. The unhealthy part is specifically when individuals are forced (consciously or not) into taking risk as a byproduct of central banks manufacturing money to lose value. Risk-taking is productive when it is intentional, voluntary, and undertaken in the pursuit of accumulating capital. While deciphering between productive investment and that which is induced by monetary inflation is inherently gray, you know it when you see it. Productive investment occurs naturally as market participants work to improve their own lives and the lives of those around them. The incentives to take risk in a free market already exist. There is nothing to be gained, and a lot to lose, through central bank intervention.

Risk-taking becomes counterproductive when it is born more out of a hostage-taking situation than free will. That should be intuitive. But it is exactly what occurs when investment is induced by monetary debasement. Recognize that 100% of all future investment (and consumption, for that matter) comes from savings. Manipulating monetary incentives and specifically creating a disincentive to save merely distorts the timing and terms of future investment. It forces the hand of savers everywhere and unnecessarily lights a shortened fuse on all monetary savings. It inevitably creates a game of hot potato, with no one wanting to hold money because it loses value when the opposite should be true. What kind of investment do you think a world like this would produce? The melting ice cube that is central bank currency has induced a cycle of perpetual risk-taking, whereby the majority of all savings are almost immediately put back at risk and invested in financial assets. This occurs either directly at the hands of an individual or indirectly by a deposit-taking financial institution. Made worse, the two operations have become so confused and conflated that most people consider investments, particularly those in financial assets, as savings.

Without question, investments (in financial assets or otherwise) are not the equivalent of savings, and there is nothing normal or natural about risk-taking induced by the disincentive to save created by central banks. Anyone with common sense and real-world experience understands that. Still, it doesn’t change the fact that money loses its value every year (because it does), and knowledge of that fact very rationally dictates behavior. Everyone has been forced to accept a manufactured dilemma. The idea that you must make your money grow is one of the greatest lies ever told. It isn’t true at all. Central banks have created that false dilemma. The greatest trick that central banks ever pulled was convincing the world that individuals must perpetually take risk just to preserve value already created (and saved). It is insane, and the only practical solution is to find a better form of money that eliminates the negative asymmetry inherent to systemic currency debasement. That is what bitcoin represents. A better form of money that provides all individuals with a credible path to opt out and get off the hamster wheel.

The Great Financialization

Whether one considers the game to be inherently rigged or simply acknowledges the reality of persistent monetary debasement, economies everywhere have been forced to adapt to a world in which money loses its value. While the intention is to induce investment and spur growth in aggregate demand (i.e., the total demand for goods and services within an economy), there are always unintended consequences when economic incentives become manipulated by exogenous forces. Even the greatest cynic probably wishes that the world’s problems could be solved by printing money. However, rather than print money and have problems magically disappear, the proverbial can has just been kicked further and further down the road. Economies have been structurally and permanently altered as a function of money creation.

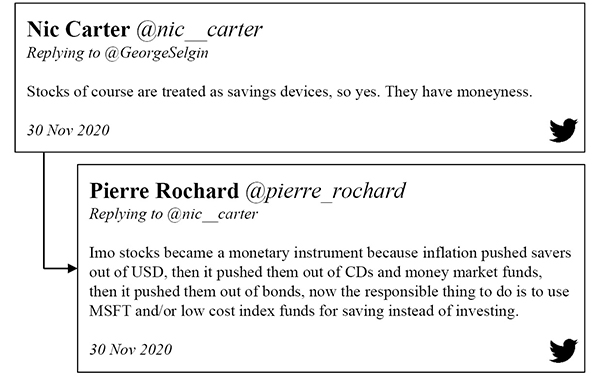

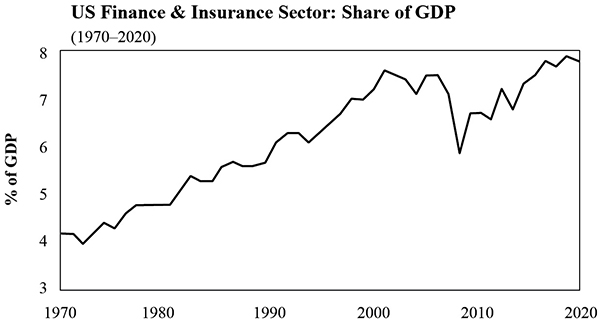

The Fed may have thought it could print money as a means to induce productive investment, but what it actually produced was malinvestment and a massively overfinancialized economy. Economies have become increasingly financialized as a direct result of monetary debasement and a manipulated cost of credit, which was an intended derivative of monetary debasement. One would have to be blind not to see the causal and interconnected relationship—a money manufactured to lose its value, a disincentive to hold money, artificially cheap credit, and the rapid expansion of financial assets, including debt instruments within the credit system.

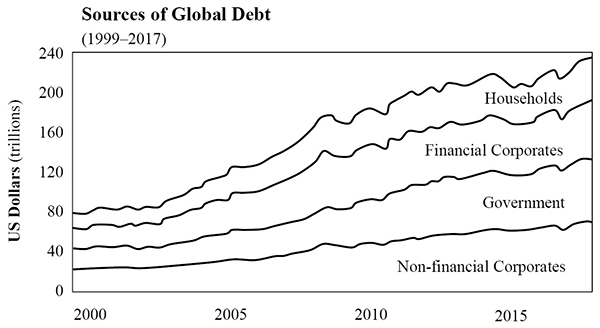

Source: Institute of International Finance

The banking and wealth management industries have metastasized by this same function. It is like a drug dealer who creates his own market by giving the first hit away for free. Drug dealers create their own demand by getting the addict hooked. The dynamic is similar between the Fed and financialization via monetary debasement. The Fed created a problem, and then a treatment for the problem was necessary. By manufacturing money to lose value, markets for financial products emerged that otherwise would not. Products have been created to help people financially engineer their way out of the very hole created by the Fed. The need arises to take risk in an attempt to produce returns to replace what is lost via monetary inflation.

Source: Statista.com

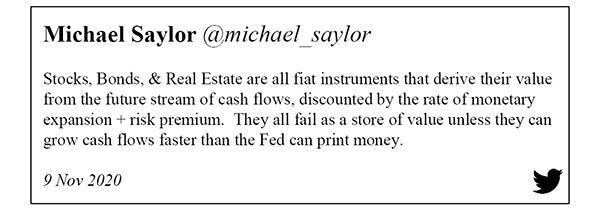

The financial sector has captured a larger percentage of the economy over time because there is greater demand for financial services in a world in which money cannot reliably be expected to store value. Stocks, corporate bonds, treasuries, sovereign bonds, mutual funds, equity ETFs, bond ETFs, leveraged ETFs, triple leveraged ETFs, fractional shares, mortgage-backed securities, CDOs, CLOs, CDS, CDX, synthetic CDS/CDX, etc.—all of these products represent the financialization of the economy, and they become more relevant (and in greater demand) when the monetary function is broken.

Source: Federal Reserve Economic Data (FRED), US Bureau of Economic Analysis

Each incremental shift to pool, package, and repackage risk can be tied back to an intentionally broken monetary incentive structure and the manufactured need to make money grow. Again, this is not to say that certain financial products or capital structures do not create value. Instead, the problem is the degree to which financial products are utilized and the extent to which risk has been layered on top of risk, resulting from the broken monetary incentives.

While the vast majority of all market participants have been lulled to sleep as the Fed has normalized an annual inflation target of 2%, consider the consequence of that policy over a decade or two decades. It represents a compounded 20% and 35% loss of monetary savings over ten or twenty years, respectively. What would one expect to occur if an entire society, individually and collectively, were put in the position of needing to recreate or replace 20% to 35% of their savings just to stay in the same place or get back to even?

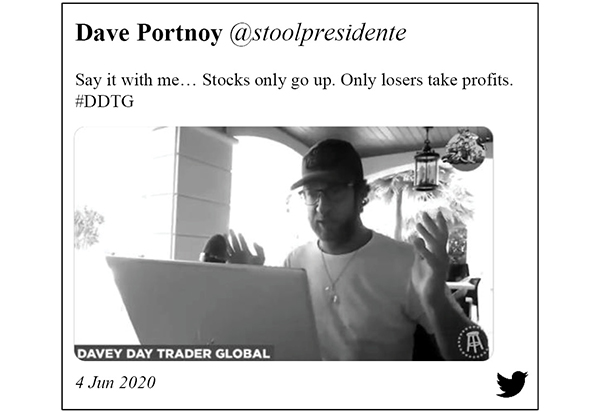

The aggregate impact is massive widespread malinvestment: investment in activities that would not have occurred if people were not forced into a position of taking ill-advised risk merely to replace the expected future loss of current savings. At an individual level, it’s the doctor, nurse, engineer, teacher, butcher, grocer, or builder turned financial investor, plowing the majority of their savings into Wall Street financial products that bear risk while perceiving there to be none. Over time, stocks only go up, real estate only goes up, and interest rates only go down.

How or why is a mystery to the Davey Day Traders of the world (for the record, the author is a Dave Portnoy fan), and it matters not. It is just how the world is perceived to work, and everyone acts accordingly. Rest assured. It will all end badly. Most individuals have come to believe that investments in financial assets are just a better (and necessary) way to save, which dictates behavior. A “diversified portfolio” has become so synonymous with savings that it is neither perceived to bear risk nor associated with actively taking risk. While this couldn’t be further from the truth, the choice is either to take risk via financial investments or to leave savings in a monetary medium that is sure to purchase less and less in the future. It is an unnerving game that everyone is forced to play. It is where “damned if you do” meets “damned if you don’t.”

Consequences of a Disincentive to Save

A negative feedback loop exists in a world where money is engineered to lose value by design. By eliminating the very possibility of saving money as a winning proposition, all outcomes skew far more negative in aggregate. Just holding money is a losing hand by default. So is perpetual risk-taking as a forced substitute. Effectively, all hands become losing hands when the possibility of winning by saving money is removed. Recall that each individual possessing money has already taken risks to get it in the first place. A positive incentive to save (and not invest) is not equivalent to rewarding people for not taking risk. It is quite the opposite. It is rewarding people who have already taken risk with the option of merely holding money without the express promise of its purchasing power declining in the future.

In a free market, money might increase or decrease in value over a particular time horizon. But guaranteeing that money will lose value creates an extremely negative outcome where the majority of participants within an economy lack actual savings. Because money loses its value, opportunity cost is often believed to be a one-way street: spend your money now because it will purchase less tomorrow. The very idea of holding cash (formerly known as saving) has been conditioned in mainstream financial circles to be a near-crazy proposition. How crazy is that? While money is intended to store value, no one wants to hold it because today’s predominant currencies do the opposite. Rather than seek out a better form of money, everyone just invests instead!

I still think that cash is trash relative to other alternatives, particularly those that will retain their value or increase their value during reflationary periods.

Even the most revered Wall Street investors are susceptible to getting caught up in the madness and can act a fool. Risk-taking for inflation’s sake is no better than buying lottery tickets, but that is the consequence of creating a disincentive to save. Economic opportunity cost becomes harder to measure and evaluate when monetary incentives are broken. Today, purchasing financial assets is rationalized merely because the dollar is expected to lose its value. But the consequence extends far beyond savings and investment. Every economic decision becomes impaired when money is not fulfilling its intended purpose of storing value.

All spending versus savings decisions, including day-to-day consumption, become negatively biased when money persistently loses value. By reintroducing a more explicit opportunity cost to spending money (i.e., an incentive to save), everyone’s risk calculus necessarily changes. Every economic decision becomes sharper when money fulfills its proper function of storing value. When a monetary medium can be credibly expected at minimum to maintain its value, if not increase, every spend-versus-save decision becomes more focused and is made with greater scrutiny when governed and informed by a better-aligned incentive structure.

One of the greatest mistakes is to judge policies and programs by their intentions rather than their results.

Keynesian economists fear such a world, believing that investments would not be made if an incentive to save existed. The flawed theory asserts that if people are incentivized to “hoard” money, no one will ever spend money, and “necessary” investments will not be made. If no one spends and risk-taking investments are not made, unemployment will rise! It truly is an economic theory reserved for the classroom. While counterintuitive to Keynesians, risk will be taken and money will be spent in a world that incentivizes savings.

Not only that, but the quality of consumption and investment will both benefit from undistorted price signals and with the opportunity cost of money more clearly priced by a free market. When all spending decisions are evaluated against the expectation of potentially greater purchasing power in the future (rather than less), investments will be steered toward the most productive activities, and day-to-day consumption will be filtered with greater scrutiny.

Conversely, when the decision point of investment is heavily influenced by an aversion to holding dollars, the result is financialization. Similarly, when consumption preferences are guided by the expectation that money will lose its value rather than increase in value, investments are made that cater toward those distorted preferences. Short-term incentives beat out long-term incentives. Incumbents are advantaged over new entrants, and the economy stagnates, which fuels financialization, centralization, and financial engineering rather than productive investment. It is cause and effect, intended behavior with unintended but predictable consequences.

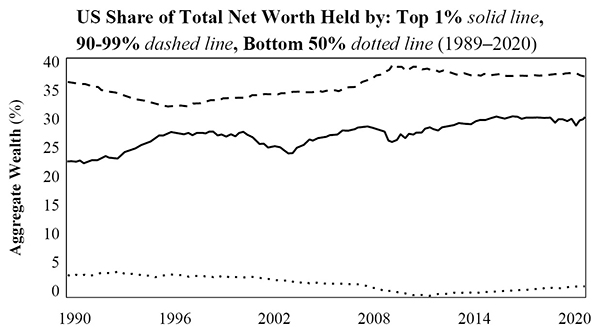

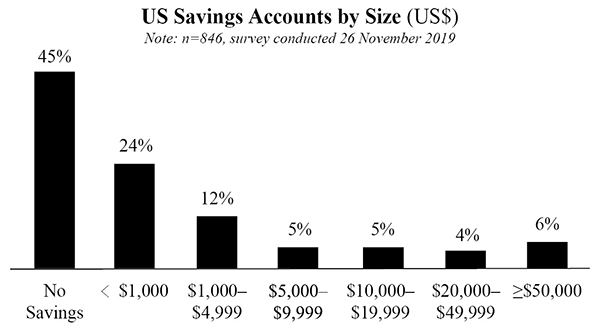

Make money lose its value, and people will do dumb shit because doing dumb shit becomes more rational (if not encouraged). People who would otherwise be saving are forced to take incremental risk because their savings are losing value. In that world, savings become financialized. And when you create a disincentive to save, do not be surprised to wake up in a world where very few people have savings. It is exactly what has happened. Although it may astound a tenured economics professor, the general lack of savings induced by the disincentive to save is very predictably a major source of the inherent fragility in the legacy financial system. Without savings, very few are prepared for any modicum of future uncertainty.

Source: Federal Reserve Economic Data (FRED)

>Source: Statista.com

The Paradox of a Fixed Money Supply

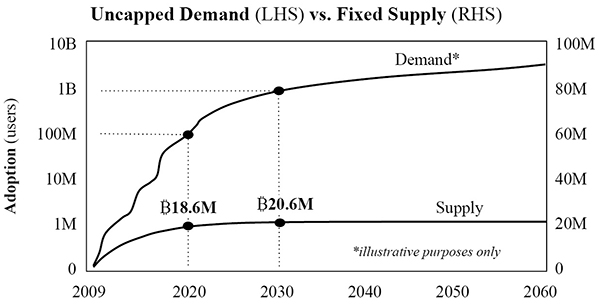

The lack of savings and economic instability that follows is all driven by the broken incentive structure of the underlying currency, and this is the principal problem that bitcoin fixes. By eliminating the possibility of monetary debasement, incentives that were broken become aligned. There will only ever be 21 million bitcoin, and that alone is sufficiently powerful to begin to reverse the trend of financialization. While each bitcoin is divisible into 100 million units (or to eight decimal places), the nominal supply of bitcoin is capped at 21 million. Bitcoin can be further divided into smaller and smaller units as more and more people adopt it as a monetary standard, but no one can arbitrarily create more bitcoin. Consider a terminal state in which all 21 million bitcoin are in circulation. Technically, no more than 21 million bitcoin can be saved, but the consequence is that 100% of all bitcoin is always being saved—by someone at any particular point in time. Bitcoin (including fractions thereof) will transfer from person to person or company to company, but the total supply will be static and perfectly inelastic.

With a fixed money supply, no more or no less money can be saved in aggregate. However, the incentive and propensity to save increases measurably at an individual level as a result. It is a paradox. If more money cannot be saved in aggregate, more people will save on an individual basis. While it may appear to be a simple statement that individuals value scarcity, it serves more as an explanation that an incentive to save creates savers. And for someone to save, someone else must spend existing savings. After all, all consumption and investment come from savings. The incentive to save creates savers, and the existence of more savers results in more people with the means to consume and invest. At an individual level, if someone expects a monetary unit to increase in purchasing power, they may reasonably defer either consumption or investment to the future (the keyword being “defer”). That is the incentive to save creating savers. It does not eliminate consumption or investment. It merely ensures that the decision is evaluated with greater scrutiny when future purchasing power is expected to increase. Imagine every single person simultaneously operating with that as an incentive mechanism, compared to the opposite that exists today.

Source: Institute of International Finance

While Keynesians worry that an appreciating currency will disincentivize consumption and investment in favor of savings—to the detriment of the economy at large—the free market actually works better in practice than it does when applying flawed Keynesian theory. An appreciating currency will be used every day to facilitate consumption and investment because there is an incentive to save, not despite that fact. Everyone is always trying to earn everyone else’s money, and everyone still needs to consume real goods every day.

The concept of time preference is described at length in The Bitcoin Standard by Saifedean Ammous (2018). While the book is a must-read and no summary can do it justice, a key idea it puts forward is that of time preference. While individuals can have a lower time preference (weighting the future over the present) or a higher time preference (weighting the present over the future), everyone has a positive time preference. As a tool, money is merely a utility in coordinating the economic activity necessary to produce the things that people value and consume in their daily lives. Given that time is inherently scarce and that the future is uncertain, even those who plan and save for the future (i.e., possessing a low time preference) are predisposed to value the present over the future on the margin. Taken to an extreme for illustrative purposes, if you earned money and literally never spent a dime (or a sat), the money would not have done you any good. Even if the value of money is increasing over time, consumption or investment in the present has an inherent bias over the future, on average, because of positive time preference and daily consumption needs that must be satisfied for survival (if not for want).

7+ Billion People Competing + 21 Million Bitcoin = Appreciating Currency + Constant Spending

Now imagine this principle applied to everyone simultaneously and in a world of bitcoin with a fixed money supply. Seven billion-plus people and only 21 million bitcoin. Everyone has both an incentive to save because there is a finite amount of money and a positive time preference with daily consumption needs. In this world, there would be fierce competition for money. Each individual would have to produce something sufficiently valuable in order to entice someone else to part with their hard-earned money. The roles would then reverse, and the cycle would repeat because it would be the only way to get money. That is the contract bitcoin provides.

The incentive to save exists, but acquiring savings requires that individuals produce something of value demanded by others. If at first you don’t succeed, try, try again. The interests and incentives align perfectly between those holding the currency and those providing goods and services because the script (and relationship) is then flipped after each exchange. Paradoxically, everyone would be incentivized to “save more” in a world in which more money technically could not be saved—the incentive for each individual to produce more is embedded in this system as well. Over time, each person would hold less and less of the currency in nominal terms on average, but each nominal unit would purchase more and more over time (rather than less). The ability to defer consumption or investment and be rewarded (or simply not be penalized) is the linchpin that aligns all economic incentives.

Bitcoin and the Great Definancialization

The primary incentive to save bitcoin is that it represents an immutable right to own a fixed percentage of all the world’s money indefinitely. There is no central bank to arbitrarily increase the supply of the currency and debase savings. By programming a set of rules that no human can alter, bitcoin will be the catalyst that causes the trend toward financialization to reverse course. The extent to which economies all over the world have become financialized is a direct result of misaligned monetary incentives, and bitcoin reintroduces the proper incentives that promote savings. More directly, the devaluation of monetary savings has been the principal driver of financialization, full stop. It should come as no surprise that the reverse set of operations will naturally course correct when the dynamic that created the phenomenon is eliminated.

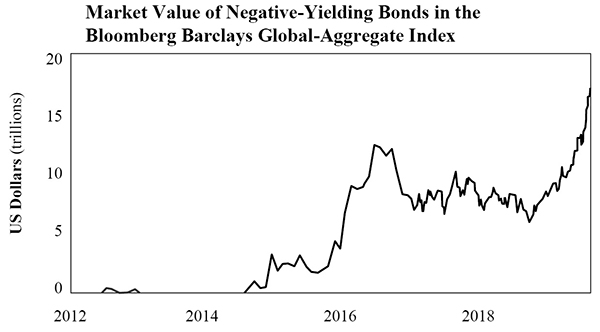

If monetary debasement induced financialization, it should be logical that a return to a sound monetary standard would have the opposite effect. The tide of financialization is already on its way out, but the groundswell is just beginning to form. And most people do not yet see it coming. For decades, the conventional wisdom has been to invest the vast majority of one’s savings. It is a practice that will not reverse overnight. But as the world learns about bitcoin against a backdrop of central banks printing trillions of dollars and anomalies like $17 trillion in negative-yielding debt, the dots will increasingly be connected.

Source: Bloomberg

The market value of the Bloomberg Barclays Global Negative Yielding Debt Index rose to $17.05 trillion [November 2020], the highest level ever recorded and narrowly eclipsing the $17.04 trillion it reached in August 2019.

More and more people will begin to question the idea of investing retirement savings in risky financial assets. Negative-yielding debt does not make sense. Central banks creating trillions of dollars in a matter of months doesn’t either. All over the world, people are beginning to question the entire construction of the financial system. What if the world didn’t have to work this way? What if it was all backward this whole time? And instead of everyone buying stocks, bonds, and layered financial risk with their savings, what if all that was ever really needed was just a better form of money?

Suppose each individual had access to a form of money that was not programmed to lose value. Rather than taking perpetual and open-ended risk, everyone could get back to saving, and the by-product would be greater economic stability. Simply go through the thought exercise. How rational is it for practically every person to invest in large public companies, bonds, or structured financial products? How much of it is invariably a function of broken monetary incentives? How much of the retirement risk-taking game came about in response to the need to keep up with monetary inflation and the devaluation of the dollar? Financialization was the lead-up to—and the blow-up that caused—the Great Financial Crisis. While not singularly responsible, the incentives of the monetary system caused the economy to become highly financialized. Broken incentives increased the amount of highly leveraged risk-taking and created a broad-based lack of savings, which was a principal source of fragility and instability. Everyone learns the acute difference between money and financial assets in the middle of a liquidity crisis. The same dynamic played out in early 2020 as liquidity crises reemerged.

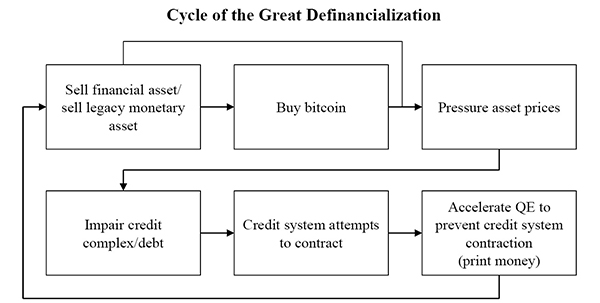

Fool me once, shame on you. Fool me twice, shame on me. Or so the saying goes. It all traces back to the breakdown of the monetary system and moral hazard introduced to the financial system by misaligned monetary incentives. There is no mistaking it. The instability in the broader economic system is a function of the monetary system. As more of these episodes continue to play out, a growing number of people will continue to seek a more sustainable path forward. With bitcoin increasingly at center stage, there is now a market mechanism that will definancialize and heal the economic system. The process of definancialization will occur as wealth stored in financial assets is converted to bitcoin, specifically as each market participant increasingly chooses to hold a more reliable form of money over risk assets.

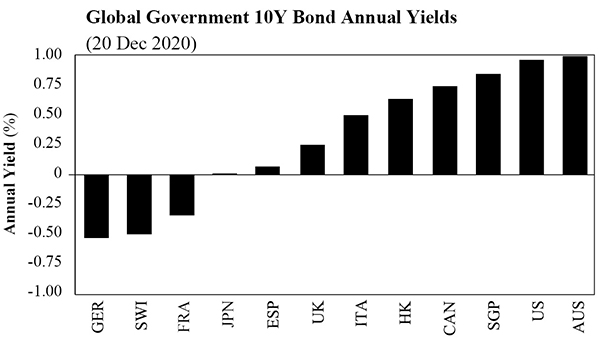

Definancialization will principally be observed through growing bitcoin adoption, the appreciation of bitcoin relative to every other asset, and the deleveraging of the financial system. Almost everything will lose purchasing power in bitcoin-denominated terms as bitcoin becomes adopted globally as a monetary standard. Most immediately, bitcoin will gain share from financial assets, which have acted as near-stores of value and monetary substitutes. It is only logical that assets that have long served as monetary substitutes will increasingly be converted to bitcoin. As part of this process, the financial system will shrink in size relative to the purchasing power of the bitcoin network. The existence of bitcoin as a more sound monetary standard will not only cause a rotation out of existing financial assets. It will also impair demand for future issuances of similar assets and products. Why purchase near-zero-yielding sovereign debt, illiquid corporate bonds, or equity-risk premium when you can own the scarcest asset (and form of money) that has ever existed?

Source: worldgovernmentbonds.com

The rotation might start with the most obviously mispriced financial assets (e.g., negative-yielding sovereign debt), but everything will ultimately be on the chopping block. Non-bitcoin asset prices will experience downward pressure, creating similar downward pressure on the value of debt instruments supported by those assets. The demand for credit will be impaired broadly, causing the credit system as a whole to contract (or attempt to contract). That in turn will accelerate the need for quantitative easing—an increase in the base money supply—to help sustain and prop up credit markets, which will further accelerate the shift out of financial assets and into bitcoin. The process of definancialization will feed on itself and accelerate because of the feedback loop between the value of financial assets, the credit system, and quantitative easing.

More substantively, as time passes and as knowledge distributes, individuals will increasingly opt for the simplicity of bitcoin (and its 21 million fixed supply) over the complexity of financial investing and structured financial risk. Financial assets bear operational and counterparty risk, whereas bitcoin is a bearer asset that is perfectly fixed in supply, highly divisible, and easily transferable. The utility of money is fundamentally distinct from that of a financial asset. A financial asset has a claim on the income stream of a productive asset denominated in a particular form of money. The holder of a financial asset is taking risks with the goal of earning more money in the future. Owning and holding money is just that. It is valuable in its ability to be exchanged in the future for goods and services. In short, money can buy groceries. Your favorite stock, bond, or treasury cannot, and there’s a reason.

There is a fundamental difference between savings and investment. Savings are held in the form of monetary assets, while investments are savings that are put at risk. The lines may have been blurred as the economic system financialized, but bitcoin will make the distinction obvious once again. Money with the proper incentive structure will overwhelm demand for complex financial assets and debt instruments. The average person will intuitively and overwhelmingly opt for the security provided by a monetary medium with a fixed supply. Consequently, the balance of power will naturally shift away from Wall Street and back to Main Street.

The banking sector will no longer reside at the epicenter of the economy as a rent-seeking endeavor. Instead, it will sit alongside every other industry and more directly compete for capital. Today, monetary capital is largely captive to the banking system, and that will no longer be true in a bitcoinized world. As part of the transition, the flow of money will increasingly disintermediate from the banking sector. Money will more freely and directly flow among the economic participants who actually contribute value in the real economy.

The function of credit markets, stock markets, and financial intermediation will still exist, but it will all be rightsized. As the financialized economy consumes fewer and fewer resources, and as monetary incentives better align with those that create real economic value, bitcoin will fundamentally restructure the economy. There have been negative societal consequences to disincentivizing savings, but now the ship is headed in the right direction and toward a brighter future. In the future, gone will be the days of everyone constantly thinking about their stock and bond portfolios, and more time will be spent getting back to the basics of life and the things that really matter.

The difference between saving in bitcoin (not taking risk) and financial investing (taking risk) is night and day. There is something cathartic about saving in a form of money that works in your favor rather than against it. It is akin to having a massive weight lifted off your shoulders that you didn’t even know existed. It might not be immediately apparent, but over time, saving in a form of money with proper incentives ultimately allows you to think and worry less about money, rather than obsessing over it. Imagine a world in which billions of people, all using a common currency, can focus more on creating value for those around them rather than worrying about making money and financial investing. What that future looks like exactly, no one knows. But bitcoin will definancialize the economy, and it will no doubt be a renaissance.

-

Ray Dalio, “I’m Ray Dalio—Founder of Bridgewater Associates and Author of Principles: Life & Work. Ask Me Anything,” Reddit, r/IamA, 7 April 2020. ↩

-

Milton Friedman, “Living Within Our Means,” interview by Richard D. Heffner, Open Minds, PBS, 7 December 1975. ↩

-

Cormac Mullen and John Ainger, “World’s Negative-Yield Debt Pile Has Just Hit a New Record,” Bloomberg, 5 November 2020. ↩