Chapter Twelve

Bitcoin Is Not a Pyramid Scheme

Originally published

on 18 October 2019

Run, Don’t Walk

A few years back, I received an email from a friend asking for my opinion about an investment opportunity that a mutual contact was considering. After some preliminary research, I explained that it looked like a pyramid scheme. This was my shorthand for “avoid at all cost.” I forwarded the information to our mutual contact, and the reply was not what I was expecting: “Are all pyramid schemes bad?” Yes. Of course. Some pyramid schemes are more difficult to identify than others, but even those that are easy to identify will find prey in unassuming victims. A good rule of thumb is to run, not walk, away from anything that even hints at being a pyramid scheme. While it may seem obvious, not everyone understands what a pyramid scheme is or knows the common warning signs. Ultimately, such schemes always fail.

A pyramid scheme is an investment fraud in which new participants’ fees are typically used to pay money to existing participants for recruiting new members. Pyramid scheme organizers may pitch the scheme as a business opportunity such as a multi-level marketing (MLM) program. Fraudsters frequently use social media, internet advertising, company websites, group presentations, conference calls, and YouTube videos to promote a pyramid scheme. All pyramid schemes eventually collapse, and most investors lose their money.

Not all multi-level marketing programs are pyramid schemes, but all pyramid schemes are multi-level marketing programs in some fashion. Pyramid schemes always involve some company or group of individuals selling a product for which the end demand falls far short of the available supply. The company recruits participants to purchase inventory and to recruit even more participants. The participants are all salespeople, and compensation is primarily tied to recruiting new participants rather than selling the actual product. Often the sale of the product is purposefully woven into the recruitment process. In a typical sales-driven business, the company takes on the inventory risk and pays commissions based on sales made to end users. In a pyramid scheme, the salespeople often take on the inventory risk (rather than the company), and compensation is provided for recruiting more salespeople who must then prepurchase their own inventory as part of the scheme. It all falls apart because sufficient end demand for the product does not actually exist. Everyone upstream can make money at the expense of the new recruits below them. This is a pyramid scheme. Bitcoin is not.

Bitcoin is not a company. It has no employees, and its supply is finitely scarce. No matter how many people adopt it, there will only ever be 21 million bitcoin. The distinctions should be glaringly obvious, but because bitcoin is nascent and the very nature of money is not well understood, confusion persists. Bitcoin will only become a global reserve currency if hundreds of millions (if not billions) more adopt it. And seemingly everyone that goes down the bitcoin rabbit hole ends up on the other side explaining it to their family and friends, pitching it as a better form of money. Sounds kind of like a pyramid scheme, right? Wrong. When Dell started selling personal computers via its website in 1996, and everyone told their friends to get a Dell, was it a pyramid scheme? When Apple released the first iPhone in 2007, and everyone told their friends to drop the Blackberry for its superior successor, was it a pyramid scheme?

Technological shifts often happen fast. Ten and twenty years later, personal computers and smartphones are ubiquitous. It is all due to the quality of the product and the incentive structure. If someone owned shares in Dell or Apple and promoted their products, did it change the fact that the product itself provided a real value proposition? Was there a direct benefit to telling people about a new technological innovation? The value proposition of an innovation trumps all else. It does not matter how you learn about it. All that matters is whether the innovation provides utility. If it does, people will want to use it. If it doesn’t, they won’t.

The Utility and Innovation of Bitcoin

Bitcoin’s utility is as money. It has a market because it solves a problem inherent in modern money. Not only is bitcoin not a pyramid scheme. It is fundamentally distinct from the class of innovation that any individual company could offer. Bitcoin is not Dell, nor is it Apple. It is not a tech stock. There is no corporate entity that exists behind bitcoin. Bitcoin is not a company selling a product. There are no revenues from which to pay future dividends. Bitcoin is a bearer asset. However, unlike a bearer bond, there is no income stream. Bitcoin is not about making money. Instead, bitcoin is itself money. Or at least, it has become money to those choosing to store a portion of their wealth in it. It is fundamentally about safeguarding the value you have already created—quite literally the opposite of a get-rich-quick scheme.

Bitcoin’s innovation is that it represents a superior form of money, which is finitely scarce. There is no future promise beyond bitcoin being a form of money that no one can print. The only utility of bitcoin is in holding it as a currency and transacting with it in the future, whether that be in exchange for legacy currencies or other goods and services. It will only maintain value if others demand it in the future, something that is true of any form of money. But money is not a collective hallucination or merely a belief system. Monetary goods have distinct properties which make them more or less effective in facilitating exchange. However, monetary properties are not absolute. The relative strength of monetary properties between two forms of money provides the fundamental basis of demand of one versus the other. When the market evaluates bitcoin, it does so relative to other monetary mediums, principally the dollar.

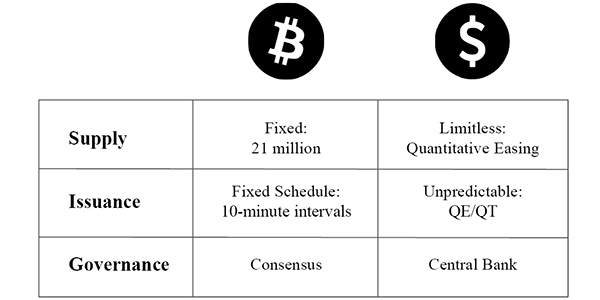

Bitcoin is distinguished from its competition in many ways, but at its most basic surface level, supply is what differentiates at the foundation. Its supply is fixed and finite in absolute quantity, it is issued at a predictable rate in both quantity and time, and it is governed by a consensus of those who hold the currency. In a pyramid scheme, supply is functionally abundant relative to demand, and fundamental demand does not actually exist beyond that which serves to perpetuate the scheme by its organizers. Skeptics who call bitcoin a pyramid scheme (or even a Ponzi scheme, for that matter) claim it only has value if people demand it in the future, suggesting it would not have value but for a “greater fool.” Everything (and anything) needs demand to maintain value. What defines a pyramid scheme is how demand is manufactured. What differentiates sound money is the fact that a supply constraint—it being hard to produce—is a key input to demand, which is not true of a pyramid scheme or any other type of good. The supply parameters and constraints of bitcoin are what serve as the basis for its demand. No matter how many people demand bitcoin, no more can be produced.

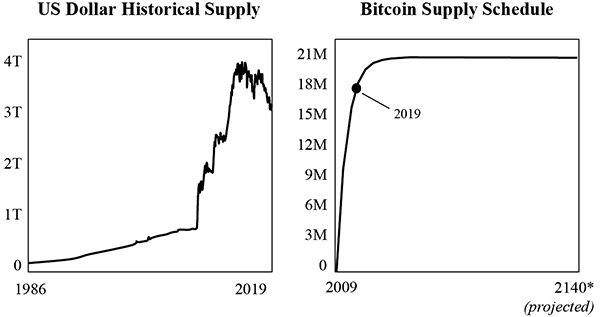

Supply—Fixed vs. Limitless

There is no greater contrast between bitcoin and its competition than its absolute supply. Dollars are becoming more and more abundant over time as the Fed creates trillions more with each passing round of quantitative easing, and there will only ever be 21 million bitcoin. Would an individual rather be paid in a form of money that cannot be printed or, conversely, in one whose supply is rapidly increasing in quantity over time? Humans rely on money to facilitate trade and exchange. The determinant question of which is better rests principally in the supply of the currency. A form of money that cannot be printed will preserve value better into the future than one that can. All incentives revolve around bitcoin’s fixed supply.

Source: Federal Reserve Economic Data (FRED)

Issuance—Predictable vs. Unknowable

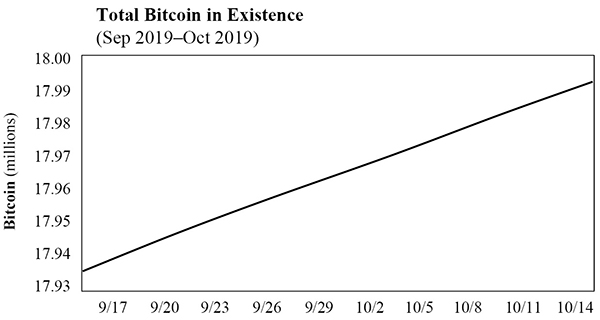

Bitcoin’s fixed supply is the foundation, but it is also issued at a predictable rate. In the future, when bitcoin reaches its maximum supply, the rate of change thereafter will be zero. But on its way to that future state, bitcoin embeds a stable and predictable supply schedule, which is a distinct and equally important part of the equation to a fixed supply. No one knows when the Fed is going to arbitrarily create more money or to what extent, in either absolute or relative terms. In contrast, bitcoin are issued through a mining process that helps secure the network, and the network adjusts to ensure that bitcoin are issued on consistent time intervals. A certain number of bitcoin are issued every ten minutes (on average). Approximately every four years, that number is cut in half until no incremental bitcoin will be issued. If more mining resources are added to the network, the network adjusts to prevent bitcoin from being issued at a faster rate. More mining results in greater levels of network security without increasing the rate of issuance or increasing the total amount of bitcoin that will ultimately be issued.

Source: satoshi.info

The enforcement of the issuance schedule every ten minutes, which must be consistent with a 21 million terminal fixed supply to be valid, builds increasing credibility in the future state supply. All market participants come to understand that the fixed supply will be enforced, not because of a magical point in time when the maximum is reached, but as a result of the network enforcing its monetary policy every ten minutes. This rigidity allows the entire economic system to plan for the future. Miners building security infrastructure are able to forecast future compensation, and all market participants can know the rate of change of the currency at any point in time.

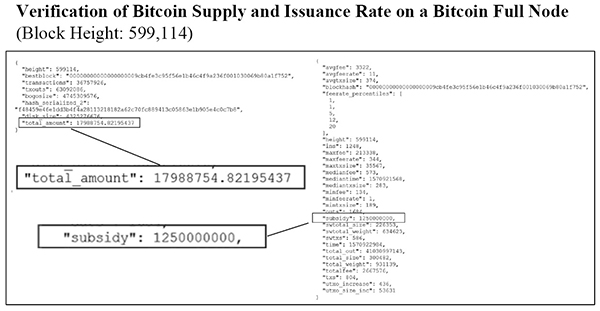

Governance—Monetary Policy by Consensus vs. Central Bank

By running a bitcoin full node, anyone can verify the number of valid bitcoin in circulation and the amount of new bitcoin issued in each block without trusting anyone else. Through this same process, the consensus of nodes actually enforces both the fixed supply and the issuance schedule at the same time. Everyone can approximate with precision when the issuance rate will be reduced and validate that it has in fact occurred with their own node. Technically, enforcement occurs every ten minutes, six times an hour, 144 times a day, 4,320 times a month, and 52,560 times a year, with each passing bitcoin block that is accepted as valid. As blocks are propagated throughout the network, each node either accepts the block as valid or rejects it as invalid. Any block that includes an amount of bitcoin to be issued inconsistent with the fixed supply is independently rejected by each node. That is enforcement, but each node can also validate at any point in time that the circulating supply and the issuance is consistent with the fixed supply of 21 million. The monetary system hardens as more market participants validate and enforce the monetary policy of the network, over and over again, every ten minutes.

The consensus mechanism that governs bitcoin is the foundation of its credibility and what ultimately sets bitcoin apart from its competition. In the central banking monetary model, twelve individuals (or thereabout) determine how and when to create billions, if not trillions, of dollars. Bitcoin, on the other hand, entrusts its monetary policy to a consensus mechanism of those that hold bitcoin as a currency. Even if an individual were to remain unconvinced that a currency with a fixed supply issued at a predictable rate is superior to one with an unpredictably inflating supply, it does not matter what any individual believes. If the market collectively determined that it would be better to remove the fixed supply cap, it is theoretically possible. However, to do so, a decentralized network (without any central coordination) would have to reach an overwhelming consensus to debase a currency that has been adopted principally for the reason that it cannot be printed. Bitcoin ultimately represents the contrast between monetary policy by consensus and monetary policy by central bank. Nothing occurs by dictate. The consensus of the network enforces the fixed supply, and everyone has an incentive to ensure that no one else can create more units of the currency arbitrarily.

Source: Personal bitcoin node

Bitcoin Is Not a Pyramid Scheme

So no, bitcoin is not a pyramid scheme. It is not organized by a sketchy company, pushing high-pressure sales tactics. It is not peddling some inferior consumer good with an abundant supply, where compensation is directly tied to recruiting new members to the scheme. Bitcoin is money, and its supply is finitely scarce. Its supply remains wholly unaffected by the level of adoption. The same pie is simply divided across more participants as adoption increases. And on average, more people control a smaller share of the network. Its value increases as a function of adoption, and adoption increases because its monetary properties are superior to the competition. Bitcoin has a fixed supply, its supply schedule is predictable, and its monetary policy is governed and enforced by consensus. Everything changes around bitcoin, but bitcoin’s fixed supply remains the constant.

Just because people who adopt bitcoin as money often advocate for it does not make it a pyramid scheme. Imagine you concluded that bitcoin is a superior form of money and that there is a fundamental and acute problem with central banks creating money arbitrarily out of thin air. Would you hide this secret from your friends and family? The skepticism for advocacy of bitcoin is healthy, but recognize that bitcoin adoption can only grow through education. If there is a moral case to educate your friends and family—which there is—it logically extends beyond that. But advocacy is not just altruistic. Most people struggle to grasp the properties that define money or to see how these properties exist in bitcoin. In many ways, bitcoin is not just a secret hiding in plain sight. It is the greatest secret that exists in the world. Once someone figures it out, often after years of denial and financial opportunity cost, it is perfectly logical to want to help others figure it out too. Some things are too good to keep secret, and there is a long-term incentive for each holder of the currency if more people adopt it. Bitcoin becomes more secure, and its utility as money increases with greater adoption.

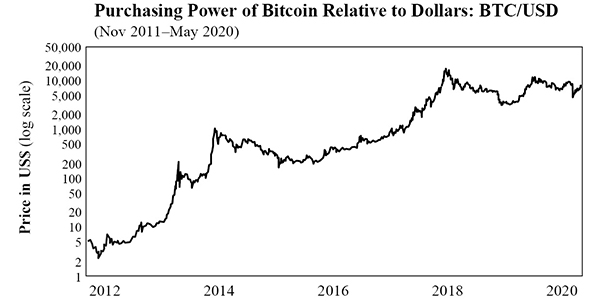

Source: Bitstamp

At the end of the day, the value of bitcoin is not dependent on any single individual figuring it out and buying in. An objective truth either exists in the world, or it does not. Bitcoin either has a fixed supply, or it does not. If it does, it will be adopted by the entire world as money. If there were more people wanting to sell their bitcoin than people needing to adopt bitcoin as money, then its price and value would decline over time. Regardless of all the people who turn into advocates for bitcoin after having adopted it or why the phenomenon exists, neither can obfuscate a fundamental economic fact, especially over the course of a decade. Knowledge distributes as a function of time. If bitcoin’s supply were not credibly fixed and if early adopters sold their bitcoin in a proportion greater than the rate of new adoption, bitcoin would not be viable as money, and its value would trend to zero rather than increase to higher and higher levels. Always anchor to the fundamentals. Why does fundamental demand exist, and is it because bitcoin is finitely scarce? If so, there is a fundamental explanation for its demand, demand will far outstrip supply, and bitcoin is not a pyramid scheme.

-

“Pyramid Schemes,” Investor.gov, US Securities and Exchange Commission. ↩