Chapter Fifteen

Bitcoin Is Common Sense

Originally published

on 1 May 2020

Old Habits Die Hard

Perhaps the sentiments contained in the following pages, are not yet sufficiently fashionable to procure them general favor; a long habit of not thinking a thing wrong, gives it a superficial appearance of being right, and raises at first a formidable outcry in defense of custom. But the tumult soon subsides. Time makes more converts than reason.

These were the opening remarks of Thomas Paine’s call for American independence in early 1776. At the time, a declaration of independence was far from a certainty, but in Paine’s view, there was no question. It wasn’t a debate. There was only one path forward. Still, he understood that public opinion had not yet caught up and naturally remained anchored to the status quo, with a preference for reconciliation rather than independence. Old habits die hard. Regardless of merit, the status quo tends to be defended, anchored in time to the way things have always been. However, truths have a way of becoming self-evident in time, more often due to common sense rather than any amount of reason or logic. One day, the truth is more likely to become painfully obvious through firsthand experience, which opens up a perspective that otherwise would not have existed, than it is from a textbook. While Paine was undoubtedly attempting to persuade an undecided populace with reason and logic, it was at the same time an appeal to not overthink what should already be self-evident based on lived experience.

In Paine’s view, independence was not a modern-day IQ test, nor was its relevance confined to the American colonies. Instead, it was a common-sense test, and its interest was universal to “the cause of all mankind.” In many ways, the same is true of bitcoin. It is not an IQ test. Bitcoin is common sense, and its implications are near-universal. Few people have ever stopped to question or understand the function of money. It facilitates practically every transaction anyone has ever made, yet no one really knows how or why. In short, the function of money is taken for granted, and as a result, it is a subject not widely taught or explored. Yet, despite a limited baseline of knowledge, there is often a visceral reaction to the idea of bitcoin as money. The default position is predictably to reject it. Bitcoin is an anathema to all notions of existing custom. On the surface, it is entirely inconsistent with what folks know money to be. For most, money is just money because it always has been. For any individual, the construction of money is anchored in time, and for most, it is very naturally not questioned.

But enter bitcoin, and suddenly everyone has a strong opinion on what is and isn’t money. To the fly-by-night expert, it is certainly not bitcoin. Bitcoin is natively digital. It is not tied to any government or central bank. It is volatile and perceived to be “slow.” It is not currently used en masse to facilitate direct commerce, and it is not inflationary. Just about every characteristic of bitcoin is inconsistent with what people associate with money. However, this is one of those rare instances where something that does not walk or quack like a duck is, in fact, a duck. And what you mistakenly thought was a duck was something entirely different all along. When it comes to modern money, the long habit of not thinking a thing wrong, gives it a superficial appearance of being right.

In its most recognized and accepted form, money is issued by a central bank. It is perceived to be relatively stable and is capable of near-infinite transaction throughput. It is widely used to facilitate day-to-day commerce, and the supply can be rapidly inflated to meet the “needs” of an ever-changing economy. Bitcoin presently has none of these traits, and as a result, it is most often dismissed as not meeting the standards of modern-day money. This is where overthinking a problem can cripple even the highest of IQs. Pattern recognition fails because the game has fundamentally changed. Most players just do not yet realize it.

Bitcoin is finitely scarce, it is highly divisible, and it is capable of being sent over a communication channel (and on a permissionless basis). There will only ever be 21 million bitcoin. Rocket scientists, brain surgeons and the most revered investors of our time could all respectively look at bitcoin and be confounded, not seeing its value. But at the same time, if posed with a straightforward question—would you rather be paid in a currency with a fixed supply that can’t be manipulated or in a currency that is subject to persistent, systemic, and significant debasement—an overwhelming majority of individuals would choose the former. All day, every day. And it wouldn’t be close.

It’s probably rat poison squared.

Bitcoin—there’s even less you can do with it. […] I’d rather have bananas. I can eat bananas.

Money Doesn’t Grow on Trees

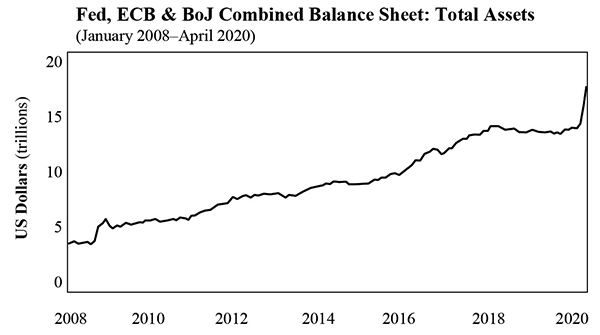

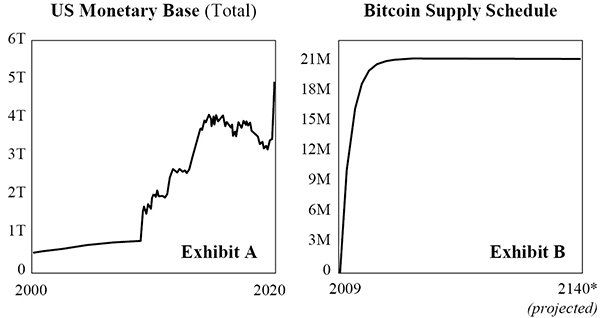

As kids, we all learn that money doesn’t grow on trees, but at a societal level or as a country, any remnant of common sense seems to have left the building. Just in the last two months, central banks in the United States, Europe, and Japan (the Fed, ECB, and BoJ) have collectively inflated the supply of their respective currencies by $3.3 trillion in aggregate—an increase of over 20%.

Source: Thomson Reuters Datastream

The Fed alone has accounted for the majority, minting $2.5 trillion and increasing the base money supply by over 60% (see Figure 13.9). It’s also far from over. Trillions more will be created. It is not just a possibility. It is a certainty. That deep feeling of uncertainty many are experiencing, the one that says “this doesn’t make any sense” or “this can’t end well”—that’s common sense speaking. Few carry that thought process out to its logical conclusion, often because it is uncomfortable to think about, but the sense of unease is reverberating throughout the country and the world. While not everyone is connecting the dots between the mass amounts of money being created and bitcoin’s fixed supply, a growing number are. Time makes more converts than reason. An individual doesn’t have to understand how or why there will only ever be 21 million bitcoin. All that must be recognized in practical experience is that dollars are going to be worth significantly less in the future, and then, the idea of a currency with a fixed supply naturally begins to make sense. In most cases, understanding exactly how bitcoin achieves its fixed supply comes after making the initial connection that the two are related. But even then, no one really needs to understand how bitcoin enforces its fixed supply to have an appreciation that a currency with a fixed supply would be valuable.

For each individual, there is a choice to either live in a world where some people get to produce new units of money for free (but just not you) or a world where no one gets to do that (including you). From an individual perspective, the difference is not marginal. It is night and day. And anyone conscious of the decision intuitively opts for the latter, recognizing that the former is neither sustainable nor to their advantage. Imagine there were one hundred individuals in an economy, each with different skills. All have determined to use a common form of money to facilitate trade in exchange for goods and services produced by others. With the one exception that a single individual among them has the superpower to print money, requiring no investment of time and at practically no cost.

Given that human time is both an inherently scarce resource and a necessary input in the production of any good or service demanded in trade, such a scenario would functionally mean that one person would get to purchase the output of all the others for free. Why would anyone agree to such an arrangement? In the real world, this individual is a central bank. The perception that a central bank is expected to act in the public’s interest does not change the fundamental operation or its consequence. If it does not make sense on a micro level, it does not magically transform into a different fundamental fact merely by introducing greater degrees of separation and opacity. If no individual would bestow that power in another person, then it follows that no one would consciously decide to bestow it in a central bank.

Everything beyond this fundamental reality strays into abstract theory, relying on leaps of faith, hypotheticals, and big words that no one understands. It is not that one individual or central bank is more trustworthy than another, but simply that no individual is advantaged by someone else having the ability to print money (regardless of identity or interests). This leaves only one alternative: each individual would be advantaged by ensuring that no other individual or entity possesses this power. The Fed may have the ability to create dollars at zero cost, but money still doesn’t grow on trees. It is more likely that a particular form of money is not actually money than it is that money has miraculously started growing on trees. While there is a long habit of not thinking this particular thing wrong, the errant defense of custom can only stray so far. Time converts everyone back into reality. At present, it is the Fed’s “shock and awe” money-printing campaign contrasted by the simplicity of bitcoin’s fixed supply of 21 million. And there is no amount of reason that can replace an observed divergence in two distinct paths.

Defending Existing Custom

There’s money and there’s credit. The only thing that matters is spending and you can spend money and you can spend credit. And when credit goes down, you better put money into the system so you can have the same level of spending. That’s what they did through the financial system and that thing worked.

As more people become aware of the Fed’s activities, it only raises more questions. Think about it for a second. Two point five trillion—$2,500,000,000,000—is a big number. Who gets the money, and why? What will the effects be? And when? Why is this even possible? All valid questions, but none change the fact that more dollars now exist and each will be worth materially less in the future. That is intuitive. However, at an even more fundamental level, recognize that the operation of printing money (or creating digital dollars) does nothing to generate economic activity. Imagine a printing press running on a loop, or simply keying in a number of dollars on a computer (which is technically all that the Fed does when it creates “money”). Such an operation does not produce anything of value in the real world. Instead, that action can only induce an individual to take some other action.

Recognize that any tangible good or service in existence must be produced by some individual or a group of individuals. Human time is the input. Capital production is the output. Whether software applications, manufacturing equipment, a service, or an end consumer good, one or more individuals had to contribute time to produce it. That time and value is what money tracks and prices, and ultimately what is traded and exchanged in return for money. Entering a large number into the computer does not produce software, hardware, cars, or homes. People produce those things, and money coordinates the preferences of all individuals within an economy, compensating value to varying degrees for time spent.

When the Fed creates $2.5 trillion in a matter of weeks, it is consolidating the power to price and value human time in the Fed’s hands. This, however, is not a suggestion that the individuals at the Fed are consciously or deliberately operating maliciously. It is just the inevitable consequence of the Fed’s actions, regardless of how well-intentioned. Again, the Fed’s operation (arbitrarily adding zeros to various bank account balances) cannot create value. All it can do is determine how to allocate new dollars. Doing so advantages some individuals, enterprises, or segments of the economy over others. In creating and allocating new dollars, the Fed replaces a market function—and one priced by billions of people—with a centralized function, greatly influencing the balance of power as to who controls the monetary capital that coordinates economic activity. Think about the distribution of money as the balance of control influencing and determining what gets built, by whom, and at what price. At the moment of creation, more money exists but there is no more human time or goods and services available as a consequence of that action. Beyond the point of creation, the Fed’s actions similarly do not, and cannot, create more jobs as a function of time or over time. There are just more dollars to distribute across the same labor force, but with a different distribution of those holding the currency. The Fed can print money (or create digital dollars), but it can’t print time, nor can it do anything but artificially manipulate the allocation of resources within an economy.

No Free Lunches, Just More Dollars

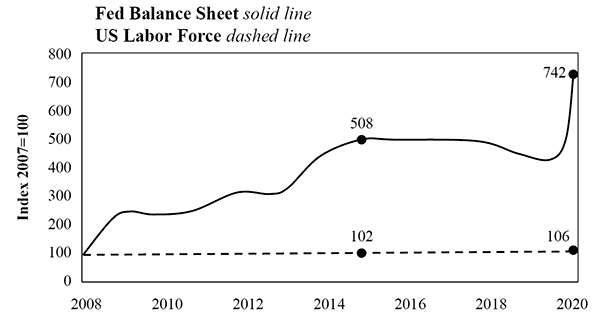

Sources: Federal Reserve Economic Data (FRED), US Bureau of Labor Statistics

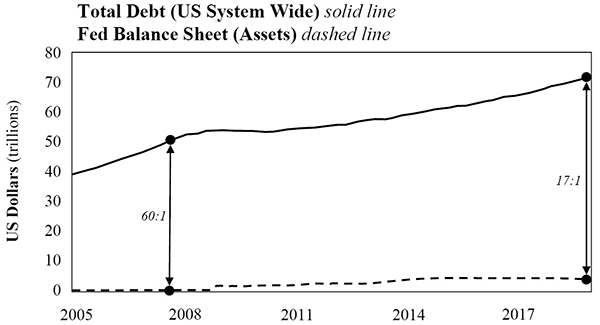

Since 2007, the Fed balance sheet has increased over seven-fold, but the labor force has only increased by 6%. There are roughly the same number of people contributing output (human time) but far more dollars available to compensate for that time. Do not be confused by the impossible-to-quantify calculation around a job saved versus a job lost. This is the US labor force, defined by the Bureau of Labor Statistics as all persons sixteen years of age and older, both employed and unemployed. The inevitable result is that the value of each dollar declines, but it does not create more workers. And prices do not all uniformly adjust to the increase in the money supply, including the price of labor.

In a theoretical world, if the Fed were to distribute the newly created money to individuals in equal proportion to the amount of currency previously held, the balance of power would not shift. In practice, the distribution of money is uneven, and the power shift is dramatic. The holders of financial assets (which the Fed purchases in the process of creating new dollars) and those with access to cheap credit (the government, large corporations, high-net-worth individuals, etc.) are heavily favored. In aggregate, the purchasing power of every dollar declines, just not immediately, and a small subset benefits at the cost of the whole (a phenomenon known as the Cantillon effect).

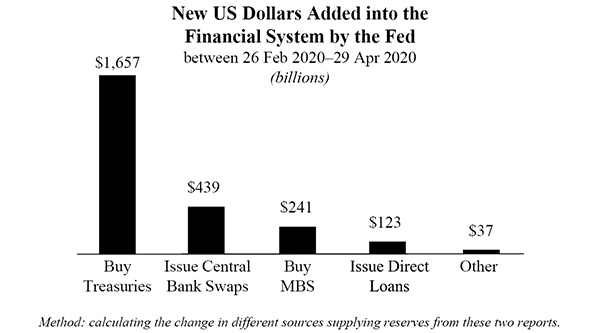

Source: Federal Reserve System (US), H.4.1 reports dated 27 Feb 2020 and 30 Apr 2020.

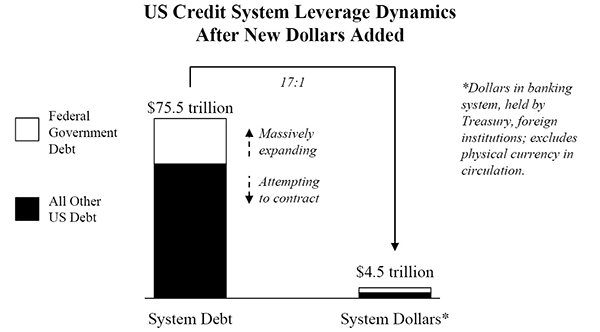

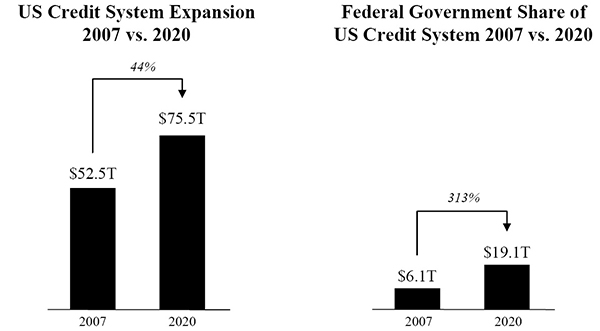

Despite the consequences, the Fed takes these actions in an attempt to support a credit system that would otherwise collapse without an ever-increasing supply of dollars. In the Fed’s economy, the credit system is the price-setting mechanism because the amount of dollar-denominated debt far outstrips the supply of dollars, which is also why the purchasing power of each dollar does not immediately respond to an increase in the money supply. Instead, the effects of increasing the money supply are transmitted, over time, through an expansion of the credit system.

Source: Board of Governors, Federal Reserve (US); data as of original publication (May 2020).

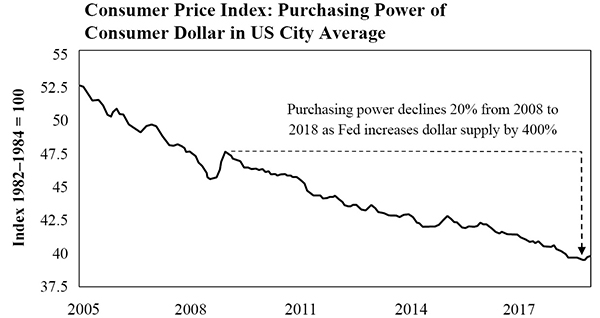

When the credit system attempts to contract, it represents the market and the individuals within an economy working to eliminate imbalances that exist. By flooding the market with dollars, the Fed prevents what otherwise would be the natural course. It overrides the market’s price-setting function and in doing so, fundamentally alters the structure of the economy. The market solution to the problem of too much debt is to reduce debt, while the Fed’s solution is to increase the supply of dollars such that existing debt levels can be sustained. The goal is to first stabilize the credit system such that it can then expand further. The 2008 financial crisis provides a historical roadmap. In its immediate aftermath, the Fed created $1.3 trillion new dollars in a matter of months. Despite this, the dollar initially strengthened as deflationary pressures in the credit system overwhelmed the increase in the money supply. However, as the credit system began to expand, the dollar’s purchasing power soon resumed its gradual decline. Currently, the cause and effect of the Fed’s monetary stimulus is primarily transmitted through the credit system. It was the case in the years following the 2008 crisis, and it will hold true this time, provided the credit system remains intact.

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics

How the effects manifest in the real economy is complicated, but it does not take any sophistication to recognize the general trajectory or to identify the foundational flaws. More dollars result in each dollar becoming worth less. And the value of any good—including monetary goods—naturally trends toward its cost to produce. The marginal cost for the Fed to produce a dollar is zero. However, all the bailouts from both the Fed and Congress, whether to individuals or companies, are ultimately paid for by someone. It is axiomatic that printing money (or creating digital dollars) does nothing to generate economic activity. It only shifts the balance of power as to who allocates the money and prices risk. It strips power from the people and centralizes it to the government. It also fundamentally impairs the economy’s function by distorting prices everywhere. But most seriously, it puts the stability of the underlying currency at risk, which is a cost everyone collectively pays. The Fed may be able to create dollars for free, and the Treasury may be able to borrow at near-zero interest rates as a direct result, but there is still no such thing as a free lunch. Someone still has to do the work, and all printing money does is shift who has the dollars to coordinate and price that work.

Source: Federal Reserve Economic Data (FRED)

The stamping of paper is an operation so much easier than the laying of taxes, that a government, in the practice of paper emissions, would rarely fail in any such emergency to indulge itself too far, in the employment of that resource, to avoid as much as possible one less auspicious to present popularity. If it should not even be carried so far as to be rendered an absolute bubble, it would at least be likely to be extended to a degree, which would occasion an inflated and artificial state of things incompatible with the regular and prosperous course of the political economy.

Source: Board of Governors, Federal Reserve System (US), Z.1 Financial Accounts of the US

“Gospodin,” he said presently, “you used an odd word earlier—odd to me, I mean…”

“Oh, tanstaafl. Means there ain’t no such thing as a free lunch. And isn’t,” I added, pointing to a FREE LUNCH sign across room, “or these drinks would cost half as much. Was reminding her that anything free costs twice as much in long run or turns out worthless.”

“An interesting philosophy.”

“Not philosophy, fact. One way or other, what you get, you pay for.”

Bitcoin Is Common Sense

Among its perceived flaws as a currency, critics view bitcoin as being too complicated to ever achieve widespread adoption. In reality, the dollar is complicated. Bitcoin is not. There will only ever be 21 million bitcoin and no one controls the supply of the currency. Not the Fed, not a CEO, not a company, not a government, not anyone. Bitcoin becomes very simple when understood through this lens. Bitcoin may be complicated at a technical level. It involves higher-level mathematics and cryptography, relies on a “mining” process, and contains several unfamiliar concepts like blocks, nodes, keys, elliptic curves, digital signatures, difficulty adjustments, hashes, nonces, and Merkle trees, among others. But with all this, bitcoin remains very simple.

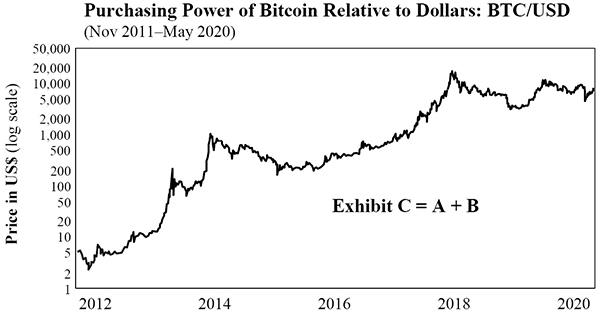

If the supply of bitcoin remains fixed at 21 million, more people will demand it, and its purchasing power will increase. Nothing about the complexity under the hood will prevent adoption. Most participants in the dollar economy (even the most sophisticated) have no practical understanding of the dollar system at a technical level. The dollar system is not only far more complex than bitcoin. It is far less transparent. Similar degrees of complexity and many of the same primitives that exist in bitcoin underlie an iPhone. Yet, individuals manage to use the iPhone successfully without understanding how it works at a technical level. The same is true of bitcoin. The innovation in bitcoin is that it achieved finite digital scarcity while being easy to divide and transfer. Twenty-one million bitcoin, period. Compare this to $2.5 trillion new dollars created by one central bank in just two months. Bitcoin’s fixed supply is the only common-sense feature anyone really needs to know.

A lot is happening in the background, but the supply of the currency drives everything. These are the dots that people worldwide are connecting. The Fed is creating trillions of dollars while bitcoin’s issuance rate continues to programmatically reduce by half approximately every four years. While most may not be aware of these two divergent paths, a growing number of people are (as knowledge distributes with time). But even a small number of people figuring it out creates a significant imbalance between the demand for bitcoin and its supply. When this happens, the value of bitcoin goes up. It is that simple and that is what draws everyone else in: price. Price is what communicates information. All those otherwise not participating react to price signals. The underlying demand is ultimately dictated by fundamentals (even if speculation exists), but the majority do not need to understand those fundamentals to recognize that the market is sending a signal.

Source: Federal Reserve Economic Data (FRED)

Source: Bitstamp

Once that signal is communicated, it then becomes clear that bitcoin really isn’t that complicated. Download an app, link a bank account, and buy bitcoin. Get a piece of hardware, the hardware generates an address, and you can send money to that address. No one can take it from you, and no one can print more. In that moment, bitcoin becomes far more intuitive. It seems complicated from the periphery, but anyone with common sense and something to lose will figure it out. The benefit is too great to ignore, and money is such a basic necessity that the bar (on a relative basis) only gets lower and lower in time. Self-preservation is the only motivation necessary to break down any remaining barriers.

A solid foundation underpins everything—bitcoin is a hard-capped money that cannot be counterfeited, is resistant to censorship and seizure, and can be secured without any counterparty risk. With that bedrock, it does not require a lot of imagination to see how bitcoin evolves from a volatile novelty into a stable currency facilitating day-to-day commerce. The contrast to the dollar is stark—a currency that becomes exponentially more expensive to produce over time versus a currency whose cost to produce is anchored forever at zero by its very nature. At the end of the day, bitcoin is a currency whose supply (and derivatively its price system) cannot be manipulated. Fundamental demand for bitcoin begins and ends at this singular cross-section. One by one, people wake up and recognize the distinction.

With bitcoin as a backdrop, it becomes self-evident that there is no advantage in ceding the power to print money or allowing a central bank to allocate resources within an economy in place of the individuals who comprise it. As each individual figures this out, bitcoin adoption grows. And as a function of that adoption, bitcoin will transition from volatile, clunky, and novel to stable, seamless, and ubiquitous. The entire transition will be dictated by value, and value is derived from the foundation that there will only ever be 21 million bitcoin. It is impossible to predict exactly how bitcoin will evolve because most of the minds that will contribute to that future have yet to comprehend it. As bitcoin captures more mindshare, its capabilities will expand exponentially beyond the span of resources that currently exist, but those resources will also come at the direct expense of the legacy system. It is ultimately a competition between two monetary systems, and the paths could not be more divergent.

Bananas grow on trees. Money does not, and there still ain’t no such thing as a free lunch. Someone is paying for everything. When governments and central banks can no longer create money out of thin air, it will become crystal clear that backdoor monetary inflation was always just a ruse to allocate resources for which no one was actually willing to be taxed. There may be debate, but bitcoin is common sense. Time makes more converts than reason.

These proceedings may at first seem strange and difficult, but like all other steps which we have already passed over, will in a little time become familiar and agreeable: and until an independence is declared, the Continent will feel itself like a man who continues putting off some unpleasant business from day to day, yet knows it must be done, hates to set about it, wishes it over, and is continually haunted with the thoughts of its necessity.

-

Thomas Paine, Common Sense (Philadelphia, January 1776). ↩

-

Warren Buffet, speech, Berkshire Hathaway Annual General Meeting, 5 May 2018. ↩

-

Mark Cuban, “Mark Cuban Answers Business Questions from Twitter | Tech Support,” YouTube, Wired, 27 September 2019. ↩

-

Ray Dalio, “Bridgewater founder Ray Dalio: We Have Two Economies Now,” interview by Joe Kernan, CNBC Squawk Box, 19 September 2017. ↩

-

Alexander Hamilton, Final Version of the Second Report on the Further Provision Necessary for Establishing Public Credit (Report on a National Bank), US Department of Treasury, 13 December 1790. ↩

-

Robert Heinlein, The Moon is a Harsh Mistress (G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1966). ↩

-

Paine, Common Sense. ↩