Triple Entry Accounting

Abstract

The digitally signed receipt, an innovation from financial cryptography, presents a challenge to classical double entry bookkeeping. Rather than compete, the two melded together form a stronger system. Expanding the usage of accounting into the wider domain of digital cash gives 3 local entries for each of 3 roles, the result of which I call triple entry accounting.

This system creates bullet proof accounting systems for aggressive uses and users. It not only lowers costs by delivering reliable and supported accounting, it makes much stronger governance possible in a way that positively impacts on the future needs of corporate and public accounting.

Introduction

This paper brings together financial cryptography innovations such as the Signed Receipt with the standard accountancy techniques of double entry bookkeeping.

The first section presents a brief backgrounder to explain the importance of double entry bookkeeping. It is aimed at the technologist, and accountancy professionals may skip this. The second section presents how the Signed Receipt arises and why it challenges double entry bookkeeping.

The third section integrates the two together and the Conclusion attempts to predict wider ramifications into Governance issues.

Credits

This paper benefitted from comments by Graeme Burnett and Todd Boyle.[1]

A Very Brief History of Accounting

Accounting or accountancy is these days thought to go back to the genesis of writing; the earliest discovered texts have been deciphered as simple lists of the counts of animal and food stock. The Sumerians of Mesopotamia, around 5000 years ago, used Cuneiform or wedge shaped markings as a base-60 number form, which we still remember as seconds and minutes, and squared, as the degrees in a circle. Mathematics and writing themselves may well have been derived from the need to add, subtract and indeed account for the basic assets and stocks of early society.

Single Entry

Single entry bookkeeping is how ‘everyone’ would do accounting: start a list, and add in entries that describe each asset. A more advanced arrangement would be to create many lists. Each list or ‘book’ would represent a category, and each entry would record a date, an amount, and perhaps a comment. To move an asset around, one would cross it off from one list and enter it onto another list.

Very simple, but it was a method that was fraught with the potential for errors. Worse, the errors could be either accidental, and difficult to track down and repair, or they could be fraudulent. As each entry or each list stood alone, there was nothing to stop a bad employee from simply adding more to the list; even when discovered there was nothing to say whether it was an honest mistake, or a fraud.

Accounting based on single entry bookkeeping places an important limitation on the trust of the books. Likely, only the owner’s family or in times long past, his slaves could be trusted with the enterprise’s books, leading to a supportive influence on extended families or slavery as economic enterprises.

Double Entry

Double Entry bookkeeping adds an additional important property to the accounting system; that of a clear strategy to identify errors and to remove them. Even better, it has a side effect of clearly firewalling errors as either accident or fraud.

This property is enabled by means of three features, being the separation of all books into two groups or sides, called assets and liabilities, the redundancy of the duplicative double entries with each entry having a match on the other side, and the balance sheet equation, which says that the sum of all entries on the asset side must equal the sum of all entries on the liabilities side.

A correct entry must refer to its counterparty, and its counterpart entry must exist on the other side. An entry in error might have been created for perhaps fraudulent reasons, but to be correct at the local level, it must refer to its counterparty book. If not, it can simply be eliminated as an incomplete entry. If it does refer, the existence of the other entry can be easily confirmed, or indeed recreated depending on the sense of it, and the loop is thus closed.

Previously, in single entry books, the fraudster simply added his amount to a column of choice. In double entry books, that amount has to come from somewhere. If it comes from nowhere, it is eliminated above as an accidental error, and if it comes from somewhere in particular, that place is identified. In this way, fraud leaves a trail; and its purpose is revealed in the other book because the value taken from that book must also have come from somewhere.

This then leads to an audit strategy. First, ensure that all entries are complete, in that they refer to their counterpart. Second, ensure that all movements of value make sense. This simple strategy created a record of transactions that permitted an accountancy of a business, without easily hiding frauds in the books themselves.

Which Came First - Double Entry or the Enterprise?

Double Entry bookkeeping is one of the greatest discoveries of commerce, and its significance is difficult to overstate. Historians think it to have been invented around the 1300s AD, although there are suggestions that it existed in some form or other as far back as the Greek empire. The earliest strong evidence is a 1494 treatise on mathematics by the Venetian Friar Luca Pacioli.[2] In his treatise, Pacioli documented many standard techniques, including a chapter on accounting. It was to become the basic text in double entry bookkeeping for many a year.

Double Entry bookkeeping arose in concert with the arisal of modern forms of enterprise as pioneered by the Venetian merchants. Historians have debated whether Double Entry was invented to support the dramatically expanded demands of the newer ventures then taking place surrounding the expansion of city states such as Venice or whether Double Entry was an enabler of this expansion.

Our experiences weigh in on the side of enablement. I refer to the experiences of digital money issuers. Our own first deployment of a system was with a single entry bookkeeping system. Its failure rate even though coding was tight was such that it could not sustain more than 20 accounts before errors in accounting crept in and the system lost cohesion. This occurred within weeks of initial testing and was never capable of being fielded. The replacement double entry system was fielded in early 1996 and has never lost a transaction (although there have been some close shaves[3]).

Likewise, the company DigiCash BV of the Netherlands fielded an early digital cash system into a bank in the USA. During its testing period, the original single entry accounting system had to be field replaced with a double entry system for the same reason – errors crept in and rendered the accounting underneath the digital cash system unreliable.

Another major digital money system lasted for many years on a single entry accounting system. Yet, the company knew it was running on luck. When a cracker managed to find a flaw in the system, an overnight attack allowed the creation of many millions of dollars worth of value. As this was more than the contractual issue of value to date, it caused dramatic contortions to the balance sheet, including putting it in breach of its user contract and at dire risk of a ‘bank run’. Luckily, the cracker deposited the created value into the account of an online game that failed shortly afterwards, so the value was able to be neutralised and monetarily cleansed, without disclosure, and without scandal.

In the opinion of this author at least, single entry bookkeeping is incapable of supporting any enterprise more sophisticated than a household. Given this, I suggest that evolution of complex enterprises required double entry as an enabler.

Computing Double Entry in Quick Time

Double Entry has always been the foundation of accounting systems for computers. The capability to detect, classify and correct errors is even more important to computers than it is to humans, as there is no luxury of human intervention; the distance between the user and the bits and bytes is far greater than the distance between the bookkeeper and the ink marks on his ledgers.

How Double Entry is implemented is a subject in and of itself. Computer science introduces concepts such as transactions, which are defined as units of work that are atomic, consistent, isolated, and durable (or ACID for short). The core question for computer scientists is how to add an entry to the assets side, then add an entry to the liabilities side, and not crash half way through this sequence. Or even worse, have another transaction start half way through. This makes more sense when considered in the context of the millions of entries that a computer might manage, and a very small chance that something goes wrong; eventually something does, and computers cannot handle errors of that nature very well.

For the most part, these concepts simply reduce to “how do we implement double entry bookkeeping?” As this question is well answered in the literature, we do no more than mention it here.

A Slightly Less Brief History of the Signed Receipt

Recent advances in financial cryptography have provided a challenge to the concept of double entry bookkeeping. The digital signature is capable of creating a record with some strong degree of reliabilty, at least in the senses expressed by ACID, above. A digital signature can be relied upon to keep a record safe, as it will fail to verify if any details in the record are changed.

If we can assume that the the record was originally created correctly, then later errors are revealed, both of an accidental nature and of fraudulent intent. (Computers very rarely make accidental errors, and when they do, they are most normally done in a clumsy fashion more akin to the inkpot being spilt than a few numbers.) In this way, any change to a record that makes some sort of accounting or semantic sense is almost certainly an attempt at fraud, and a digital signature makes this obvious.

The Digital Signature and Digital Cash

A digital signature gives us a particular property, to whit:

“at a given point in time, this information was seen and marked by the signing computer.”

There are several variants, with softer and harder claims to that property. For example, message digests with entanglement form one simple and effective form of signature, and public key cryptosystems provide another form where signers hold a private key and verifiers hold a public key.[4] There are also many ways to attack the basic property. In this essay I avoid comparisons, and assume the basic property as a reliable mark of having been seen by a computer at some point in time.

Digital signatures then represent a new way to create reliable and trustworthy entries, which can be constructed into accounting systems. At first it was suggested that a variant known as the blinded signature would enable digital cash.[5] Then, certificates would circulate as rights or contracts, in much the same way as the share certificates of old and thus replace centralised accounting systems.[6] These ideas took financial cryptography part of the way there. Although they showed how to strongly verify each transaction, they stopped short of placing the the digital signature in an overall framework of accountancy and governance. A needed step was to add in the redundancy implied in double entry bookkeeping in order to protect both the transacting agents and the system operators from fraud.

The Initial Role of a Receipt

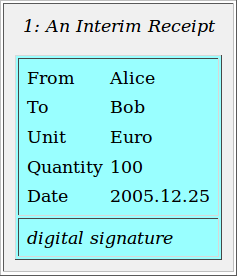

Designs that derived from the characteristics of the Internet, the capabilities of cryptography and the needs of governance led to the development of the signed receipt.[7] In order to develop this concept, let us assume a simple three party payment system, wherein each party holds an authorising key which can be used to sign their instructions. We call these players Alice, Bob (two users) and Ivan (the Issuer) for convenience.

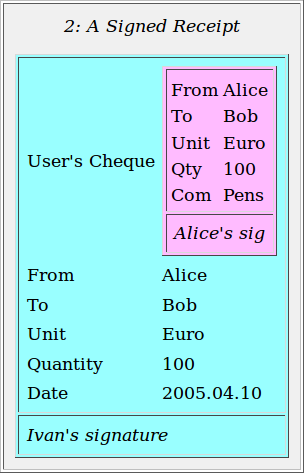

When Alice wishes to transfer value to Bob in some unit or contract managed by Ivan, she writes out the payment instruction and signs it digitally, much like a cheque is dealt with in the physical world. She sends this to the server, Ivan, and he presumably agrees and does the transfer in his internal set of books. He then issues a receipt and signs it with his signing key. As an important part of the protocol, Ivan then reliably delivers the signed receipt to both Alice and Bob, and they can update their internal books accordingly.

The Receipt is the Transaction

Our concept of digital value sought to eliminate as many risks as possible. This was derived simply from one of the high level requirements, that of being extremely efficient at issuance of value. Efficiency in digital issuance is primarily a function of support costs, and a major determinant of support costs is the costs of fraud and theft.

One risk that consistently blew away any design for efficient digital value at reasonable cost was the risk of insider fraud. In our model of many users and a single centralised server, the issuers of the unit of digital value (as signatory to the contract) and any governance partners such as the server operators are powerful candidates for insider fraud. Events over the last few years such as the mutual funds and stockgate scandals are canonical cases of risks that we decided to address.

In order to address the risk of insider fraud, the written receipt was historically introduced as being a primary source of evidence. Mostly forgotten to the buying public these days, the purpose of a written receipt in normal retail trade is not to permit returns and complaints by the customer, but rather to engage her in a protocol of documentation that binds the shop attendant into safekeeping of the monies. A good customer will notice fraud by the shop attendant and warn the owner to look out for the monies identified by the receipt; the same story applies to the invention of the cash till or register, which was originally just a box separating the owner’s takings from the monies in the shop attendant’s pockets. We extend this primary motive into the digital world by using a signed receipt to bind the Issuer into a governance protocol with the users.

We also go several steps further forward. Firstly, to achieve a complete binding, Alice’s original authorisation is also included within the record. The receipt then includes all the evidence of both the user’s intention and the server’s action in response, and it now becomes a dominating record of the event. This then means that the most efficient record keeping strategy is to drop all prior records and keep safe the signed receipt.

This domination affects both the Issuer and the user, and allows us to state the following principle:

The User and the Issuer hold the same information.

As the signed receipt is delivered from Issuer to both users, all three parties hold the same dominating record for each event. This reduces support costs by dramatically reducing problems caused by differences in information.

Secondly, we bind a signed contract of issuance known as a Ricardian Contract into the receipt.[8] This invention relates a digitally signed document securely to the signed receipt by means of a unique identifier called a message digest, again provided by cryptography. It provides strong binding for the unit of account, the nature of the issue, the terms, conditions and promises being made by the Issuer, and of course the identity of the Issuer.

Finally, with these enabling steps in place, we can now introduce the principle:

The Receipt is the Transaction.

Within the full record of the signed receipt, the user’s intention is expressed, and is fully confirmed by the server’s response. Both of these are covered by digital signatures, locking these data down. A reviewer such as an auditor can confirm the two sets of data, and can verify the signatures.

The Signed Receipt as a Bookkeeping system

The principle of the Receipt as the Transaction has become sacrosact over time. In our client software, the principle has been hammered into the design consistently, resulting in a simplified accounting regime, and delivering a high reliability. Issues still remain, such as the loss of receipts and the counting of balances by the client side software, but these become reasonably tractable once the goal of receipts as transactions is placed paramount in the designer’s mind.

As Single Entry

In order to calculate balances on a related set of receipts, or to present a transaction history, a book would be constructed on the fly from the set. This amounts to using the Signed Receipt as a basis for single entry bookkeeping. In effect, the bookkeeping is derived from the raw receipts, and this raises the question as to whether to keep the books in place.

The principles of Relational Databases provide guidance here. The fourth normal form directs that we store the primary records, in this case the set of receipts, and we construct derivative records, the accounting books, on the fly.[9]

Recovering Double Entry

Similar issues arise for Ivan the Issuer. The server has to accept each new transaction on the basis of the available balance in the effected books; for this reason Ivan needs those books to be available efficiently. Due to the greater number of receipts and books (one for each user account), both receipts and books will tend to exist, in direct contrast to fourth normal form. A meld between relationally sound sets of receipts and double entry books comes to assist here.

Alice and Bob both are granted a book each within the server’s architecture. As is customary, we place those books on the liabilities side. Receipts then can be placed in a separate single book and this could be logically placed on the assets side. Each transaction from Alice to Bob now has a logical contra entry, and is then represented in 3 places within the accounts of the server. Yet, the assets side remains in fourth normal form terms as the liabilities entries are derived, each pair from one entry on the assets side.

By extension, a more sophisticated client-side software agent, working for Alice or Bob, could employ the same techniques. At this extreme, entries are now in place in three separate locations, and each holding potentially three records.

Triple Entry Accounting

The digitally signed receipt, with the entire authorisation for a transaction, represents a dramatic challenge to double entry bookkeeping at least at the conceptual level. The cryptographic invention of the digital signature gives powerful evidentiary force to the receipt, and in practice reduces the accounting problem to one of the receipt’s presence or its absence. This problem is solved by sharing the records – each of the agents has a good copy.

In some strict sense of relational database theory, double entry book keeping is now redundant; it is normalised away by the fourth normal form. Yet this is more a statement of theory than practice, and in the software systems that we have built, the two remain together, working mostly hand in hand.

Which leads to the pairs of double entries connected by the central list of receipts; three entries for each transaction. Not only is each accounting agent led to keep three entries, the natural roles of a transaction are of three parties, leading to three by three entries.

We term this triple entry bookkeeping. Although the digitally signed receipt dominates in information terms, in processing terms it falls short. Double entry book keeping fills in the processing gap, and thus the two will work better together than apart. In this sense, our term of triple entry bookkeeping recommends an advance in accounting, rather than a revolution.

Software Considerations

The precise layout of the entries in software and data terms is not settled, and may ultimately become one of those ephemeral implementation issues. The signed receipts may form a natural asset-side contra account, or they may be a separate non-book list underlying the bookkeeping system and its two sides.

Auditing issues arise where construction of the books derives from the receipts, and normalisation issues arise when a receipt is lost. These are issues for future research.

Likewise, it is worth stating that the technique of signing receipts works both with private key signatures and also with entanglement message digest signatures; whether the security aspects of these techniques is adequate to task is dependent on the business environment.

Roles of the Agents

It will be noted that the above design of triple entry bookkeeping assumed that Alice and Bob were agents of some independence. This was made possible, and reflected the usage of the system as a digital cash system, and not as a classical accounting system.

Far from reducing the relevance of this work to the accounting profession, it introduces digital cash as an alternate to corporate bookkeeping. If an accounting system for a corporation or other administrative entity is recast as a system of digital cash, or internal money, then experience shows that benefits accrue to the organisation.

Although the core of the system looks exactly like an accounting system, each department’s books are pushed out as digital cash accounts. Departments no longer work so much with budgets as have control over their own corporate money. Fundamental governance control is still held within the accounting department by dint of their operation of the system, and by the limited scope of the money as only being usable within the organisation; the accounting department might step in as a market maker, exchanging payments in internal money for payments in external money to outside suppliers.

We have operated this system on a small scale. Rather than be inefficient on such a small scale, the system has generated dramatic savings in coordination. No longer are bills and salaries paid using conventional monies; many transactions are dealt with by internal money transfers and at the edges of the corporation, formal and informal agents work to exchange between internal money and external money. Paperwork reduces dramatically, as the records of the money system are reliable enough to quickly resolve questions even years after the event.

The innovations present in internal money go beyond the present paper, but suffice to say that they answer the obvious question of why this design of triple entry accounting sprung from the world of digital cash, and has relevence back to the corporate world.

Patterns of Commerce

Todd Boyle looked at a similar problem from the point of view of small business needs in an Internet age, and reached the same conclusion – triple entry accounting.[10] His starting premises were that:

- The major need is not accounting or payments, per se, but patterns of exchange – complex patterns of trade;

- Small businesses could not afford large complex systems that understood these patterns;

- They would not lock themselves into proprietary frameworks;

From those foundations, Boyle concluded that therefore what is needed is a shared access repository that provides arms-length access. Fundamentally, this repository is akin to the classic double-entry accounting ledger of transaction rows (“GLT” for General Ledger - Transactions), yet its entries are dynamic and shared.

Simple examples will help. When Alice forms a transaction, she enters it into her software. Every GLT transaction requires naming her external counterparty, Bob. When she posts the transaction, her software stores it in her local GLT and also submits it to the shared repository service’s GLT.

The Shared Transaction Repository (“STR”) then forwards the transaction on to Bob. Both Bob and Alice are now expected to store the handle to the transaction as an index or stub, and the STR then stores the entire transaction.

Boyle’s ideas are logically comparable to Grigg and Howland’s, although they arive from different directions (the STR is Grigg’s Ivan, above) and are not totally equivalent. Where the latter limited themselves to payments, the accuracy of amounts, and protection with hard cryptographic shells, Boyle looked at wider patterns of transactions, and showed that the STR could mediate these transactions, if the core shared data could be extracted and made into a single shared record. Boyle’s focus was on the economic substance of the transaction.

Extending the Humble Invoice

Imagine a simple invoicing procedure. Alice creates an invoice and posts it to her software (GLT). As she has named Bob, the GLT automatically posts it to Ivan, the STR, and he forwards it to Bob. At this point Bob has a decision to make, accept or reject. Assuming acceptance, his software can then respond by sending an acceptance message to Ivan. The STR now assembles an accepted invoice record to replace the earlier speculative invoice record and posts that threeways. At some related time (to do with payment policy) Bob also posts a separate transaction to pay for the invoice. This could operate in much the same way as a separate transaction, linking directly to the original invoice.

Now, as the payment links back, and the invoice is a live transaction within the three entries in the three accounting systems, it is possible for a new updated invoice record to refer back to the payment activity. When the payment clears, the new record can again replace the older unpaid copy and promulgate to all three parties.

Patterns of Transactions

Software could be written to facilitate and monitor this flow and similar flows. If the payments system is sufficiently flexible, and integrated with the needs of the users, if might be possible to merge the above invoice with the payment itself, at the Receipts level. Seen in this light, the Signed receipt of Ricardo is simply the smallest and simplest pattern within the more general set of patterns. We could then suggest that the narrow principle of the Receipt is the Transaction could be extended into The Invoice is the Transaction.

A particular transaction in business almost never stands alone. They come in patterns. For example offers and acceptances form a wider transaction but seldom encapsulate the entire fulfillment and payment cycle. Even if there has been a payment accompanying a PO message, the customer then waits for fulfillment.

There is a large body of science and literature built around these patterns of transactions. These have been adopted by the Business Process workgroup of ebXML and other standards bodies, where they are called “Commercial Transactions.” Where however the present work distinguishes itself is in breaking down these transactions into the atomic elements. It is to that we now turn.

The Requirements of Triple Entry Accounting

The implementation of Triple Entry Accounting will in time evolve to support patterns of transactions. What has become clear is that double entry does not sufficiently support these patterns, as it is a framework that breaks down as soon as the number of parties exceeds one. Yet, even as double entry is “broken” on the net and unable to support commercial demands, triple entry is not widely understood, nor are the infrastructure requirements that it imposes well recognised.

Below are the list of requirements that we believed to be important.[11][12]

1. Strong Psuedonymity, At Least. As there are many cycles in the patterns, the system must support a clear relationship of participants. At the minimum this requires a nymous architecture of the nature of Ricardo or AADS. (This requirement is very clear, but space prevents any discussion of it.)

2. Entry Signing. In order to neutralise the threats to and by the parties, a mechanism that freezes and confirms the basic data is needed. This is signing, and we require that all entries are capable of carrying digital signatures (see 1, above, which suggests public key signatures).

3. Message Passing. The system is fundamentally one of message passing, in contrast to much of the net’s connection based architecture. Boyle recognised early on that a critical component was the generic message passing nature, and Systemics proposed and built this into Ricardo over the period 2001-2004.[13]

4. Entry Enlargement and Migration. Each new version of a message coming in represents an entry that is either to be updated or added. As each message adds to a prior conversation, the stored entry needs to enlarge and absorb the new information, while preserving the other properties.

5. Local Entry Storage and Reports. The persistent saving and responsive availability of entries. In practice, this is the classical accounting general ledger, at least in storage terms. It needs to bend somewhat to handle much more flexible entries, and its report capabilities become more key as they conduct instrinsic reconciliation on a demand or live basis.

6. Integrated Hard Payments. Trade can only be as efficient as the payment. That means that the payment must be at least as efficient as every other part; which in practice means that a payment system should be built-in at the infrastructure level. C.f., Ricardo.

7. Integrated Application-Level Messaging. As distinct to the messaging at the lower protocol levels (1 above), there is a requirement for Alice and Bob to be able to communicate. That is because the vast majority of the patterns turns around the basic communications of the agents. There is no point in establishing a better payment and invoice mechanism than the means of communication and negotiation. This concept is perhaps best seen in the SWIFT system which is a messaging system, first and foremost, to deliver instructions for payments.

Conclusion

Double Entry bookkeeping provides evidence of intent and origin, leading to strategies for dealing with errors of accident and fraud. The financial cryptography invention of the signed receipt provides the same benefits, and thus challenges the 800 year reign of double entry. Indeed, in evidentiary terms, the signed receipt is more powerful than double entry records due to the technical qualities of its signature.

There remain some weaknesses in strict comparison with double entry bookkeeping. Firstly, in the Ricardo instantiation of triple entry accounting, the receipts themselves may be lost or removed, and for this reason we stress as a principle that the entry is the transaction. This results in three active agents who are charged with securing the signed entry as their most important record of transaction.

Secondly, the software ramifications of the triple entry system that are less convenient than that offered by double entry bookkeeping. For this reason, we expand the information held in the receipt into a set of double entry books; in this way we have the best of both worlds on each node: the evidentiary power of the signed entries and the convenience and local crosschecking power of the double entry concept.

Both of these imperitives meld signed receipts in with double entry bookkeeping. As we end up with a logical arrangement of three by three entries, we feel the term triple entry bookkeeping is useful to describe the advance on the older form.

Drawing in the Agents

To fully benefit from triple entry bookkeeping, we have to expand accounting systems out to agents and offer them direct capabilities to do transactions. That is, we make the agents stakeholders by giving them internal money.[14] Use of digital cash to do company accounts empowers the use of this concept as a general replacement for accounting using books and departmental budgets, and is an enabler for verifying and auditing the centralised accounts system by way of signed receipts.

Solving Frauds

Once there, governance receives substantial benefits. Accounts are now much more difficult to change, and much more transparent. It is our opinion that various scandals and failures of governance would have been impossible given these techniques: the mutual funds scandal would have shown a clear audit trail of transactions and thus late timing and otherwise perverted or dropped transactions would have been clearly identified or eliminated completely.[15] The emerging scandal in the USA known as Stockgate would have been impossible as forgery of shares and value for manipulative trading purposes is revealed by signed receipts. Likewise, Barings would still be a force in investment banking if accounts had been organised around easily transparent digital cash with open and irreducible signed receipts that evidence invisible accounts (88888). Enron style scandals would have permitted more direct “follow the money” governance lifting the veil on various innovative but economically meaningless swaps.

References

-

A draft form of this paper credited Todd Boyle as an author, but this was later withdrawn at his request due to wider differences between the views. ↩

-

Friar Luca Pacioli, Summa de Arithmetica, Geometria, Proportioni et Proportionalita 1494, Venice. ↩

-

Ian Grigg "The Twilight Zone," Financial Cryptography blog 16th April 2005 ↩

-

Entanglement is discussed in: Petros Maniatis and Mary Baker, "Secure History Preservation through Timeline Entanglement," Proc. 11th USENIX Security Symposium, August 2002. ↩

-

David Chaum, "Achieving Electronic Privacy," Scientific American, v. 267, n. 2 Aug 1992. ↩

-

Robert A. Hettinga "The Book-Entry/Certificate Distinction" 1995, Cypherpunks ↩

-

Gary Howland "Development of an Open and Flexible Payment System" 1996, Amsterdam, NL. ↩

-

Ian Grigg "The Ricardian Contract," First IEEE International Workshop on Electronic Contracting (WEC) 6th July 2004 ↩

-

E.F. Codd, "A Relational Model of Data for Large Shared Data Banks," Comm. ACM 13 (6), June 1970, pp. 377-387. ↩

-

Todd Boyle, "GLT and GLR: conceptual architecture for general ledgers," Ledgerism.net, 1997-2005. ↩

-

Todd Boyle, "STR software specification," Goals, 1-5. This section adopts that numbering convention. ↩

-

Ian Grigg, various design and requirements documents, Systemics, unpublished. ↩

-

A substantial part of the programming and design was conducted by Edwin Woudt (first demo, SOX layers, UI) and Jeroen van Gelderen (message passing client architecture). ↩

-

Using internal money instead of an accounting system is not a new idea but has only been recently experienced: Ian Grigg, How we raised capital at 0%, saved our creditors from an accounting nightmare, gave our suppliers a discount and got to bed before midnight. Informal essay (rant), 7 Jul 2003. ↩

-

James Nesfield and Ian Grigg "Mutual Funds and Financial Flaws," U.S. Senate Finance Subcommittee 27th January, 2004 ↩