The Playdough Protocols

Commercial security at the birth of writing, arithmetic, and religion in ancient Sumer (modern Iraq).

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Seals and Sealing

- Clay Documents and Envelopes

- Tamper Evident Numbers

- Modern Sealing

- Conclusion

- References

- Acknowledgements

Introduction

It is five thousand years ago, and you pace fretfully in your office. Located in the temple of the great goddess Inanna in ancient Nippur (now in Iraq) you are buried, not in a blizzard of paper, but an avalanche of clay. You fret. You have entrusted a valuable cargo of sheep, barley, and beer to a crusty group of sailors from the Baba Temple in the nearby Lagash[1]. These navy types are far from pious devotees of the goddess Inanna and the great god Enlil with whom you are familiar.

The sailors‘ job, and your payoff – take the goods down the Persian Gulf and across the sea to Mohenjo-Daro, in the valley of the Indus River (in modern Pakistan). There they will be delivered to your old friend, a trusted agent of Inanna, and sold to the locals for a very substantial amount of silver.

Will the sailors get hungry and eat the sheep and barley? Party and drink the beer? Get nasty and poison the lot, throwing disrepute on the great goddess Inanna? Perhaps they will get clever and water down the beer – or get still more clever and resell your high-quality goods under the name of their crude god.

You needn‘t worry so much. Long-distance commerce may be a novelty, but you have the clay.

Nor, thanks to five thousand years of experience with the technologies of tamper evidence, need we worry so much in our modern era. The occasional embezzlement and rare but quite nasty poisoning occur far less often due to our technological and institutional descendants of the ancients‘ clay. And using the digital equivalent of seals, we can bring data integrity and unforgeable identities to online commerce.

Seals and Sealing

Let‘s follow the professional archaeologists and distinguish between seals, the often cleverly carved cylinders or stamps that make the impressions, and sealings, the resulting impressions rolled or stamped on wet clay, and the clay they were impressed upon. Sealings of clay were wrapped around rope knots to seal bales of goods, and around the rims of wicker baskets and pottery jars to seal in their contents. Since these ancients lacked good locks, clay sealings were wrapped around door latches to seal rooms. The security provided – evidence of tampering, due to damage of the container itself or the clay that sealed it.

Seals were carved from hard materials – usually stone but sometimes faience, glass, metal, wood, or bone. Sometimes sun-dried or baked clay itself was used. The Greeks and Romans used signet rings, their action ends shaped from metal or carved from gems, to stamp wax.

The seal design was usually recessed, resulting in a raised impression; occasionally this was reversed. To creating a sealing, first wet clay was shaped around the plug of a jar, the rim of a basket, the knot of a well wrapped rope on a bale, or the latch of a door. Then the surface of the clay was thoroughly covered by the impressions of the seal. The Sumerians commonly used cylinder seals, repeating the pattern across the entire clay surface. Sometimes stamp seals were used for smaller surfaces. Finally, the clay was left to dry, in the sun if possible.

While sun-dried clay could usually be remoistened and rewritten, it would have been very difficult to hide from a trained eye. Rejoining the breached container lid, knot, or latch and replacing the broken seal with a new, identical seal would have been, short of stealing the original unique seal carving, impossible to hide from the inspector. Looking for a particular seal impression and examining the container, the inspector could reliably tell whether the contents had been tampered with. The difference between an accidental crack, from dropping or hitting the object, and a breach that allowed the thief or adulterator access to the goods, would also be apparent. Ancient inspectors undoubtedly became experts at looking for clues to distinguish accident from fraud. In any case, a broken seal then as now indicated suspect goods suitable perhaps for the discount bin, but more normally for the trash. It also indicated error for fraud – and potential punishment.

The earliest stamp seals found were used in Iran in 5,000 B.C. Later on archaeologists can use both the trade in seals themselves, as well as the distances between seals and the corresponding sealings, to trace long-distance trade networks. One such set of seals were manufactured around 1,900 B.C. on two important island trading cities in the Persian Gulf – Bahrein and Failaka. These seals were traded all over the Middle East, and have been found at diverse and distant locations such as Susa in Iran , Bactria in Afghanistan, Ur in Iraq, and Lothal on the west coast of India. By 1,750 B.C. Common Style seals are found in locations ranging from Spain, to Mycenaean Greece, to Marlik near the shores of the Caspian Sea. These seals were made from faience, a less expensive material, and used by smaller merchants.[2]

The first cylinder seals belonged to the now long dead civilization of the Sumerians, the inhabitants of Nippur, Lagash, and other cities on the Euphrates and Tigris rivers in what is now Iraq. They spoke a strange language – neither Semitic nor Indo-European, the family of languages spoken by many later civilizations and the most current inhabitants of the Middle East. Sumerian was an agglunative tongue, bearing resemblance to such diverse agglutinative languages as Turkish, Finnish, Japanese, and Dravidian. Indeed, it was probably some version of the latter tongue that was spoken by their neighbors, the early inhabitants of the Indus river valley. These Indus valley people developed, soon after the Sumerians, their own civilization and unique style of seals. Modern speakers of Dravidian languages are scattered all over the Indian subcontinent, including remnants in Afghanistan and a large number of Tamils in southern India. Seal impressions have been found in the ancient city of Harrapan, in the Indus River valley (modern Pakistan), that had been made by seals found in Lagash in Sumeria (modern Iraq). From 3,600 B.C. in Sumer, and a little later in the Indus Valley, we can find seals made out of a rare high-quality stone, lapis lazuli. These stones could only have originated from rather distant and inaccessible mines in Afghanistan.

For the Sumerians a business protocol was also a religious ritual, and the reverse was usually true as well. In the Middle East seal breaking became one of the most important of these rituals, with terrifying spiritual consequences if the seal were broken by the wrong person or at the wrong time. Three thousand years later these poetic images had reached apocalyptic proportions in the writings of the early Christian mystic John. The grave religious powers that could be unleashed by breaking a seal are well illustrated by his book of Revelations, in which the breaking of the first four seals of a holy book release the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse:

6:1 And I saw in the right hand of him that sat on the throne a book written within and on the backside, sealed with seven seals.

6:2 And I saw a strong angel proclaiming with a loud voice, Who is worthy to open the book, and to loose the seals thereof? …

A worthy deity is found, who starts breaking the seals and thereby loosing the Horsemen –

6:5 When he opened the third seal, I heard the third living creature saying, “Come and see!” And behold, a black horse, and he who sat on it had a balance in his hand.

6:6 I heard a voice in the midst of the four living creatures saying, “A choenix of wheat for a denarius, and three choenix of barley for a denarius! Don‘t damage the oil and the wine!”[3]

The Sumerians used thin wires and flat ingots of gold and silver, carefully weighed in balance scales, rather than coins like the Roman denarius. Except for paying the price in coins rather than coils, the commerce of the Third Horseman would have sounded quite familiar to our Sumerian merchant.

Clay Documents and Envelopes

The first documents ever written, in the 4th millennium B.C., were also about wheat and barley, and also sealed. Far earlier still, at least as far back as 8,000 B.C., archeologists have found even more alient artifacts – vast numbers of little clay tokens. In the first half of the 20th century archaeologists, looking for important artifacts of civilization like statues of gods and Moses-style law tablets, dismissed these tokens as some kind of trivia, probably game tokens or cheap unstrung beads. Now we know that these tokens led directly to what are now the very basics of our civilization – reading, writing, and arithmetic.

Recall our merchant, entrusting goods to sailors. Not all goods could be sealed in a jar or small room – a flock of sheep entrusted to shepherds, for instance. And in some cases it was expected that goods would be have to be opened en route – for example, to be audited by a customs inspector. For this reason, a separate record of the goods was needed. Without writing, how was such a record created?

Pebbles, shells, and other counters have long been used to count things. Without even knowing how to verbally count in order – some cultures do not have words for numbers above three – one can “count” objects by placing a pebble, on a pile or in a bag, one for each object. One nomadic tribe in Africa[4] counts cattle passing through a gate by drilling furrows. As each cattle paces, a pebble is placed in the rightmost furrow. When there are nine pebbles in this furrow, and the tenth cow goes through the gate, the pebbles are removed from the first furrow and a single is placed in the next furrow to the left. This is a “carry” operation, used in abacuses around the world and even used in modern computers. These nomads have, along with many other cultures, invented a kind of abacus, with a ones place, a tens place. A zero is simply an empty furrow. Many other cultures (though not this one) have taken this to the next step and used this abacus, in the form of pebbles on a board or beads strung on rods, to add, subtract, multiply, and perform other computations. Indeed, until the advent of our modern Arabic numbers, everywhere calculations were done by the abacus or fingers, not on paper.

In the ancient Middle East, these pebbles took the form of dried clay tokens. The clay was formed into pebbles of various shapes and sizes. Some represented sheep, some standard sized pots of barley, and so on. The number of kinds grew as commerce grew. Some represented one, five, or a dozen of the kind.

Soon after 4,000 B.C., the clay tokens were combined with the idea of sealing to create bills of lading and warehouse receipts. To create a bill of lading for a consignment of sheep, the owner put in a one-sheep token for every sheep. Every time he counted five sheep, a five-sheep token could be substituted for a one-sheep token. Once the owner and the consignee agreed on the count, the tokens were placed in a wet clay envelope. The owner and the consignee rolled their seals over the envelope, then let it dry. The procedure for a warehouse receipt was similar. An owner of wheat or barley could consign his fresh harvest to the protection of a warrior-priest in his walled fortress. The receipt was tokens sealed in an envelope – when the owner got hungry, or wanted to sell to the hungry, or wanted the seed to plant next spring – he would take the envelope to the warehouse. The claimant and the warehouse operator would inspect the seal, break it, inspect the tokens, and then deliver the goods.

It would be nice if one could learn the contents of the envelope – the number and kind of tokens – without having take the ominous and irreversible step of breaking the seal. Around 3,400 B.C. in Sumer, marks started appearing on the outside of these envelopes. These marks were simply made by the tokens themselves. The different shapes and sizes of the tokens created correspondingly unique impressions, and thus the same symbols.[4][5]. Such external marks weren‘t as secure – they could be erased, albeit not without detection by a well trained eye.

As warehouse receipts and bills of lading became common, commerce diversified. So many different kinds and numbers of goods were involved that the shapes and sizes of clay tokens were growing out of control. What computer scientists call a “level of indirection” was needed. With different tokens for one sheep, five sheep, one pot of barley, five pots of barley, and so forth, we get m*n different tokens, where m are the numerical denominations of the tokens and n are the number of different kinds of commodities. By creating separate tokens for the numbers and the goods, the number of different kinds of tokens were reduced to m + n, at the cost of up to twice as many tokens per envelope.

This development wasn‘t entirely new. Abstract counting tokens, reused for sheep and people and pots of barley, are probably far more ancient. Nor were separate words for “sheep”, and “barley” new. What was new were the separate tokens for “sheep”, “barley”, to be used, like the counting tokens, in the bills of lading and warehouse receipts. The were still thought of as corresponding to the objects they represented, not the words “sheep” and “barley”, but it was a big step towards written language. Naturally these symbols also became external marks[4][5].

The first written tablets, dating around 3,300 B.C. and again in Sumer, were simply these external marks, inscribed on clay tablets. To maintain the security properties of tokens in clay envelopes, some the tablets were themselves are sealed in clay envelopes.

The evolution of writing proceeded from there. A hundred years later reed styluses were being used to badly mimic the clay token marks. Over succeeding centuries, scribes supplemented or replaced token-derived symbols with pictographs for the objects. The pictographs attempted to bring to mind the object visually. Both kinds of symbols became stylized as wedges, or “cuneiform”, optimized for the reed stylus. Still later, words represented by neither pictographs nor token-derived symbols come to be represented by a rebus. An example of a rebus in English is representing the word “I” with a pictographic symbol for “eye”. This gave rise to a semi-phonetic alphabet. From this evolved the Phoenician or true phonetic alphabet, which was in turned borrowed by the Greeks and Romans. We use the Roman alphabet.

Tamper Evident Numbers

Evolving beyond clay tokens, accounting was the first use of the external marks and started to take a familiar form. Along with the tamper evident clay, the Sumerians developed a kind of virtual tamper evidence. It took the form of two sets of numbers. On the front of the tablet, each group of commodities would be recorded separately – For example on the front woudl be recorded 120 pots of wheat, 90 pots of barley, and 55 goats. On the reverse would simply be recorded “265” – the same objects counted gain, probably in a different order, and without bothering to categorize them. The scribe, or an auditor, would then verify that the sum was correct. If not, an error or fraud had occured. Note the similarity to tamper evident seals – if a seal is broken, this meant that error or fraud had occured. The breaker of the seals, or the scribe who recorded the wrong numbers, or the debtor who paid the wrong amounts of commodities would be called on the carpet to answer for his or her discrepancy.

Checksums still form the basis of modern accounting. Indeed, the principle of double entry bookeeping is based on two sets of independently derived numbers that must add up to the same number. Below, we will see that modern computers, using cryptographic methods, can now compute unspoofable checksums.

Modern Sealing

Breaking a seal still, but fortunately only quite rarely, can have implications that are apocalyptic – at least for the individuals involved. Tylenol in 1982 and 1986, Excedrin and Lipton Cup-A-Soup in 1986, Sudafed in 1991, and Goody’s Headache Powder in 1992 all were tampered with by sickos who added cyanide to the product and killed people. This spurred a new emphasis on tamper evident plastic packaging which can now be found protecting a wide variety of the products we use.

Everybody is familiar with shrink-wrapped plastic, a less secure but commonly used technology – as common as the ubiquitous price tag. Another favorite tamper-evident device is the seal used to protect pill bottles.

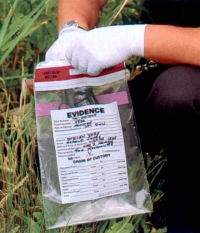

Bank employees, our modern descendants of ancient temple accountant-priests, still sometimes work in edifices designed to look like Roman temples. They carry cash, checks, and other valuables in tamper-evident clear plastic envelopes. Evidence of tampering comes either as a tear in the plastic, or from opening the bag normally. In the latter case, a seal (the same place you’d find the zip seal on a Zip-Loc bag) chemically alters, and words such as “VOID” or “OPENED” appear in large letters. When these bags carry unique serial numbers, inspectors at both ends can record the serial number while examining the bag for tampering. The unique serial number prevents the tamperer from simply transferring the contents from one such bag to another. Modern plastic bags with the altering chemical seal, used in conjunction with the tracking of unique serial numbers, provide a very strong kind of tamper evidence, and are used by high security institutions ranging from banks to the military to cryptographic certificate authorities. The evidence bags used by many police departments work the same way.

Many other kinds of security, from ancient to modern, can be thought of as providing a kind of tamper evidence. Laser-break and glass-break sensors can make an entire building trespass evident. Similarly, guard dogs bark to protect their territories, alterting their masters to visitors.

One of the most high-tech kinds of security, cryptography, is no longer just secret writing, but has spawned a whole new family of mathematical functions to protect the integrity of digital data. These functions are quite analogous to the function of ancient seals.

One cryptographic function, the hash function, acts like the Sumerian checksum described above. The difference is that the “numbers” it adds up are the binary digits that make up text, images, or other data. A second difference is that, by using a one way function and very large numbers, it can make the checksum practically unspoofable. The way accountants normally use checksums, the fraudster can sometimes with some ingenuity guess what the input numbers are. With cryptographic hash functions, this is practically impossible for a human, and for a computer it would almost always take millions of years of brute-force guessing to reverse-engineer the checksum.

Another cryptographic protocol, the “digital signature”, resembles one of these ancient seals much more than it does a modern autograph. The protocol operates in two steps. In the first step, a piece of data is sealed using a hash function as describe above. This is analogous to surrounding a basket lid with clay. Then a reverse public key cryptography operation (mathematically equivalent to decrypting a message) is performed. This second step is analogous to rolling the cylinder on the seal to identify the sealer.

The digital signature can be made only by the possessor of a private key just as a seal could be made only by the possessor of the unique seal carving. If the digital signature is bad, this provides evidence that the data was tampered with or the signature forged.

References

-

Rhee, 1981 ↩

-

Colon, Dominique, Near Eeastern Seals ↩

-

Book of Revelations, Ch. 6 ↩

-

Ifrah, Georges, The Universal History of Numbers, John Wiley & Sons 1998, pg. 73 ↩ ↩ ↩

-

Schmandt-Bessarat, Denise, Accounting with Tokens in the Ancient Near East

Acknowledgements

My thanks to Andrew Odlyzko and K. Eric Drexler for their insightful comments.

Please send your comments to nszabo (at) law (dot) gwu (dot) edu