Against the Minimum Majority Measure

First published on David A. Harding's blog

Balaji Srinivasan and Leland Lee of the company 21 Inc. recently posted a detailed article about measuring Bitcoin’s decentralization. This is a description of some concerns I have with the article:

1. Naming things after Satoshi Nakamoto

The article proposes a name for the minimum number of individuals within a collection of groups necessary to represent greater than 50% of any of those groups. The name proposed is “minimum Nakamoto coefficient”.

I’m not fond of naming things after Bitcoin creator Satoshi Nakamoto. I understand that it’s often done out of respect for Nakamoto and what he achieved by inventing, programming, and maintaining Bitcoin—but it’s also often done to in order to promote a product or an idea by associating it with Nakamoto’s well-deserved fame.

I suggest that we name products, ideas, and other things after the people actually involved in creating them or with other unique branding.

In this case, English actually already has a word for describing the minimum number of individuals within a group necessary to represent more than 50% of that group: majority.

That means we can either call this concept the minimum Srinivasan-Lee coefficient or descriptively call it the minimum majority measure. I’ll use the later term in this article as I don’t want to name things after people without their permission.

2. Measuring things that ought not to be measurable

Srinivasan and Lee measure 6 things for their minimum majority calculation:

- Hashrate by self-reported miner name

- Full nodes by self-reported version

- Developers by count of self-identified commits

- Full nodes by IP address (IPv4 and maybe IPv6 receiving nodes only)

- Exchanges by self-reported volume

- Balances by self-chosen addresses

I think it’s notable that all six of these things don’t have to be—and ideally wouldn’t be—measurable. Let’s go through the list again:

-

Hashrate is only measurable because miners choose to put their names into blocks—wasting block space and making themselves the target for attackers in the process. Ideally, we’d have many small and anonymous miners.

-

Full node versions are routinely faked on the network today. Ideally, people would stop paying attention to this statistic so that developers could use it as intended to figure out which versions were still popular enough to require support; if that doesn’t happen, this field will become increasingly meaningless.

-

Developers choose what to put in their commit listings and many besides Nakamoto have chosen to give false names or even random strings. Ideally code changes and reviews would be conducted entirely anonymously, at least until the change was deployed, so that there’d be no reason to compromise developers.

-

Full node IP addresses are also easy to fake, although at some cost per IPv4 address. Ideally, everyone would use Tor or a stronger anonymity relay network.

-

Exchanges have been known to publish fake volume numbers or to craft policies that lead to high amounts of volume in the absence of underlying demand. Ideally exchanges wouldn’t keep unnecessary logs of their customer activity.

-

Balances are something that could be much more distributed today given that new addresses are free to create and free to use if you’re receiving a new transaction anyway. Ideally something like confidential transactions will deployed on Bitcoin in the future so that it won’t be possible for third parties to monitor balances.

Given that we will hopefully work towards making these things harder to measure in the future (particularly hashrate and balances), I think the minimum majority measure has limited utility even without any other problems.

3. Not objective

Given that things such as miner names, full node versions, developer commit listings, full node IP addresses, and exchange volume can be faked, one needs to subjectively adjust for that possible faking. This makes measurements more arbitrary and comparisons more difficult.

For example, 21’s own bitnodes node monitoring service, which is used as the source for two of the measurements, only counts nodes that accept receiving connections. By some measurements, this represents less that 5% of the total node count—but that alternative measurement has its own problems which need to be corrected for.

Edit: This section was slightly rephrased to address a concern from the original authors about the phrase “objective”. (diff)

4. Why we need decentralization (the main point)

Bitcoin users want many things, but I think the most important is that they don’t want their bitcoins to disappear from their wallets or become unspendable. There are two ways this can happen in Bitcoin:

-

A reorganization of the block chain can undo previous transactions, removing bitcoins from the wallets of the people who received those transactions.

-

A consensus change can invalidate bitcoins that were previously valid and spendable.

Defense against reorganization

The defense against reorganization is mining (hashrate) decentralization. A majority of hashrate can theoretically reorganize the chain as far back as they want, invalidating any transaction, and (theoretically) at no extra cost.

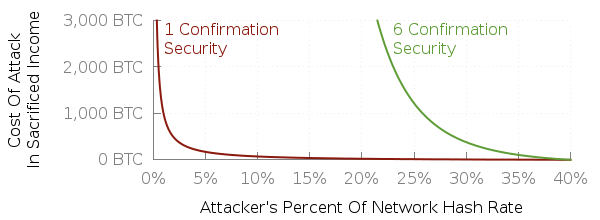

Less than a majority can also reorganize the chain to invalidate a previous transaction, but they have to sacrifice resources to do so and that sacrifice is greater the more confirmations a transaction has but lesser the more hash rate the attacking miner or miners control.

Here’s a quick plot I made back when the block reward was 25 BTC per block and transaction fees were negligible (so I could ignore them and Bitcoin Core’s anti-fee-sniping):

If no miner controls more than 1% of hashrate, then once-confirmed transactions are pretty safe against attacking miners (though not accidental conflicting blocks). If no miner controls more than 10% of hashrate, then six-confirmed transactions are quite safe.

That’s the first type of decentralization Bitcoin needs—mining decentralization. The minimum majority measure only applies here to the first part, where we worry about a miner or mining cartel with greater than a majority share; the minimum majority measure doesn’t consider that we also have to worry about a minority who are willing to spend money to make their attack.

Defense against consensus change

If every Bitcoin user wanted to pay Alice more than they wanted anything else in the world, Alice would get to define the Bitcoin consensus rules—but that means the safety of your bitcoins would depend entirely on Alice’s policies.

However, if half of all Bitcoin users wanted to pay Alice more than anything else and half wanted to pay Bob more than anything else, then Alice and Bob would have to either agree on the consensus rules or split the network with different rules. This would be a bit safer: if Alice decided to steal your bitcoins, there would at least be a chance that Bob wouldn’t.

As we extend this from Alice and Bob to Charlie, Dan, and more and more people who someone wants to pay, there are more and more people who have a say in defining the consensus rules—even though on average they each individually have a smaller say.

What they can do to combine their voices is to choose software that automatically enforces the rules they think are important and the non-objectionable rules that they think other people think are important.[1] That’s what full nodes do, and the more people who use full nodes to process the payments they receive, the harder it is to change Bitcoin’s consensus rules in a way that would hurt you.

I believe this is what Nakamoto was trying to describe when he said that he didn’t think that alternative implementations were a good idea. Even with two or more implementations of what the developers and users think are exactly the same consensus rules, there’s a chance that an accidental bug could divide that economic union.

Some people worry about developers attempting to take control, but the defense against that is for other developers to review their code and sound an alarm if they see something inappropriate. Creating multiple codebases creates more work for reviewers, increases the chance of consensus-breaking bugs, and ultimately weakens the economic union that enforces the consensus rules.

There is no way I know to measure economic enforcement except by attempting to change Bitcoin’s consensus rules. Happily, after several years of people expending considerable resources to do that, the rules have only changed for the better and in relatively small ways (BIP66 strict DER, BIP65 CLTV, BIP68/112/113 sequence/RCLTV/median-time, and soon BIP141/etc segwit).

However, there is an important metric related to ensuring economic enforcement remains intact: Cost Of Node OPeration (CONOP), which is described in quite a bit of detail at the preceding link.

Conclusion

Srinivasan’s and Lee’s article attempts to quantify Bitcoin’s decentralization using metrics that aren’t objective, may not be available in the future, and some of which are entirely unrelated to the reasons Bitcoin needs decentralization—or even contrary to keeping the system decentralized.

An alternative strategy that has been reasonably successful at maintaining decentralization on Bitcoin to date is to attempt to mitigate problems known to cause centralization among miners (e.g. the original Fast Block Relay Protocol [and Network] to mitigate the high orphan risk that caused GHash.io to obtain a majority of hashrate even after executing a $100,000 double spend attack) and to keep cost of node operation low to ensure large numbers of people can validate the transactions they receive with their own full nodes.

I personally suspect that Bitcoin’s steadily improving privacy will prevent us from ever measuring decentralization in a truly objective way. Losing easy quantification but gaining stronger privacy seems like a good tradeoff to me.

Full nodes users also have to enforce the non-objectionable rules they think other people think are important in order to form a unified economic bloc. For example, if Alice thinks the 1 MB block size is important but doesn’t care about subsidy halvings and Bob things subsidy halvings are important but doesn’t care about the 1 MB block size, they can form a economic union stronger than either of them individually by each enforcing both rules. ↩︎